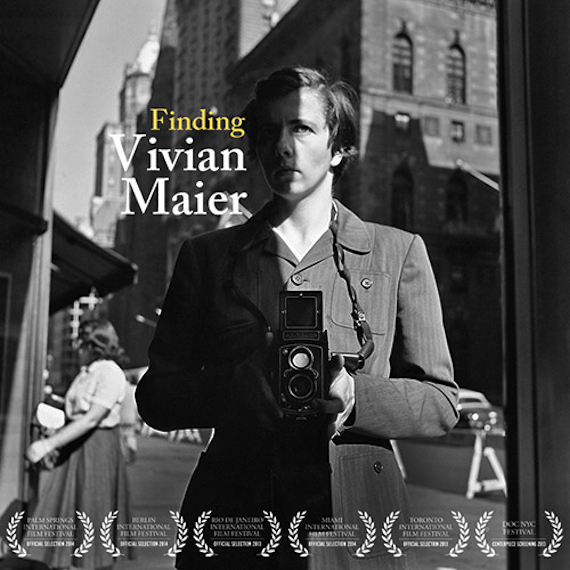

The documentary Finding Vivian Maier recently joined the burgeoning conversation about its titular subject, a reclusive Chicago nanny whose collection of street photography was discovered at a storage auction shortly before her death in the form of thousands of undeveloped rolls of film. John Maloof, the lucky man who bought her negatives, started developing and sharing the photos on Flickr. Bolstered by the positive response, he applied for an exhibition at the Chicago Cultural Center that immediately became, as I recall, the only thing to talk about at brunch in spring 2011.

Since then, the critical attention, reputation, and mystery of Vivian Maier has only grown, with some calling her one of the greatest street photographers of the 20th century. All of her known work is owned either by Maloof or Jeffrey Goldstein, another Chicago collector, both of whom work full-time managing their collections. There have been three books, with a fourth coming this fall, two documentaries, at least one feature film in pre-production, and exhibitions all over the world.

Born in 1926, Maier grew up in New York and France before moving to Chicago in 1956, where she lived until her death in 2009. For most of that time she worked as a nanny for a long string of local families (including, for a short time, Phil Donohue’s). When interviewed for the documentary, her former employers and charges elaborate on the twin pillars of her posthumous reputation: she was always taking pictures, and she was a little crazy.

Some stick with “eccentric” and a few are more comfortable suggesting mental illness — especially those who knew her later in her life — but the emerging picture of a woman who insisted on padlocking her bedroom door, hoarded newspapers, receipts, and movie stubs, and refused to give people her real name helps to explain why someone who was clearly passionate about photography never tried to share her work.

Maloof, who co-directs, narrates, and figures prominently in the documentary, approaches this question for two obvious reasons. The first is that the enigma of Vivian Maier and her work is indeed fascinating. The second is to assure the viewer — or himself, as someone who now makes a nice livelihood off the photos she never shared — that he would have had her blessing.

In his review of the film, Anthony Lane took umbrage with one of Maloof’s early takes to camera, in which he asks, stupefied, “Why is a nanny taking all these photos?” The better question, and the question that more accurately reflects Maloof’s obviously high opinion of Maier, is: Why is someone who takes so many photos a nanny? Why didn’t she ever develop her film? There is evidence that she knew she was a good photographer, was proud of her talent, but none that she attempted to share it or have it critiqued.

It’s possible that the right answer is the prosaic one — that she was a single woman working as a nanny and no one would have paid attention. Or it may be that what can mildly be described as her control issues made sharing her work seem unappealing. Maloof’s position — and again, it could be a self-justifying one — is that her work is meant to be shared, that great art deserves recognition regardless of Maier’s intentions. It seems possible to me that Maier was genuinely ambivalent about whether her photography was ever appreciated.

It left me thinking about the role that recognition plays in an artistic life. Describing some of Maier’s employers that appeared in the film, Lane writes: “none can quite believe that art, of a serious nature, was going on under their noses.” No better proof of our capacity to ignore the art under our noses is needed than 20 Feet from Stardom, another recent documentary, this one about back-up singers.

It left me thinking about the role that recognition plays in an artistic life. Describing some of Maier’s employers that appeared in the film, Lane writes: “none can quite believe that art, of a serious nature, was going on under their noses.” No better proof of our capacity to ignore the art under our noses is needed than 20 Feet from Stardom, another recent documentary, this one about back-up singers.

That film introduces about a dozen women who have worked as back-up singers at various times since the 1960s — some quit when it became clear they wouldn’t rise any higher, some are still trying to break through, and some have made decades-long careers of singing back-up. The stories in 20 Feet from Stardom are presented with much less narrative bias than Finding Vivian Maier, but the central question that arises in each of them is: if you spend your life artistically, but unnoticed, is it enough?

Each of the singers is tremendously talented. They’re touted as peers to Aretha Franklin, Whitney Houston, Tina Turner, and the likes of Sting, Mick Jagger, and Bette Midler appear in the film testifying to their greatness. They all aspire(d) to solo careers, and have attempted them to varying degrees of success. Their inability to make it big is attributed to timing, luck, and sometimes a lack of the killer instinct, but never to a lack of talent.

Their stories are full of both immense gratitude and extreme disappointment. Their unconditional love for music permeates the film, and it’s hard to feel too sorry for someone whose safety net is touring with The Rolling Stones. (One of the film’s subjects, Lisa Fischbeck, has a solo Grammy, another, Darlene Love was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and, after the film came out, got to sing her acceptance speech at the Oscars.) And yet, the source of disappointment is right there in the title — they are literally so close, steps away from their dream. Like Vivian, they worked and worked and it didn’t make them famous, but unlike Vivian, they were hoping it would.

I remember reading an interview with Jonathan Safran Foer a few years ago about the value of art that no one sees. Imagine my delight when I searched for it and realized he was talking about another documentary I could watch — Rivers and Tides about the artist Andy Goldsworthy. Goldsworthy makes art in the natural world out of natural materials — in the film he makes a sculpture out of ice and stone that melts when the sun comes up, and an igloo-like structure out of branches in a river bed that floats away when the tide changes. Although he photographs his work, the physical art that he creates generally disappears in a matter of days, sometimes hours, often before anyone besides himself has seen it.

I remember reading an interview with Jonathan Safran Foer a few years ago about the value of art that no one sees. Imagine my delight when I searched for it and realized he was talking about another documentary I could watch — Rivers and Tides about the artist Andy Goldsworthy. Goldsworthy makes art in the natural world out of natural materials — in the film he makes a sculpture out of ice and stone that melts when the sun comes up, and an igloo-like structure out of branches in a river bed that floats away when the tide changes. Although he photographs his work, the physical art that he creates generally disappears in a matter of days, sometimes hours, often before anyone besides himself has seen it.

But, Goldsworthy says, “it doesn’t feel at all like destruction.” For him, the artwork is not just the finished, viewed object, but the process of interacting with the natural world to create something and then letting that natural world take it away. “I haven’t simply made the piece to be destroyed by the sea. The work has been given to the sea as a gift, and the sea has taken the work and made more of it than I could have ever hoped for.”

For very different reasons for each of these artists, the practice of their craft looms larger than recognition of it. Watching these films reminded me of a scene in Sister Act 2, obviously, in which Whoopi Goldberg’s character is encouraging Lauryn Hill’s character to nurture her singing talent. She says, “If you wake up in the morning and you can’t think of anything but singing first, then you’re supposed to be a singer, girl.”* Or as Fischbeck says in 20 Feet from Stardom, “Some people will do anything to get famous. I just want to sing.”

For very different reasons for each of these artists, the practice of their craft looms larger than recognition of it. Watching these films reminded me of a scene in Sister Act 2, obviously, in which Whoopi Goldberg’s character is encouraging Lauryn Hill’s character to nurture her singing talent. She says, “If you wake up in the morning and you can’t think of anything but singing first, then you’re supposed to be a singer, girl.”* Or as Fischbeck says in 20 Feet from Stardom, “Some people will do anything to get famous. I just want to sing.”

By Sister Act 2 standards, Maier, Goldsworthy, Fischbeck, and Love are all artists, but these films looks at their complicated relationships to artistic recognition. Despite the accomplishment denoted in its title, Finding Vivian Maier has the murkiest picture of its subject. Making a documentary about a secretive person after her death means having to make much of very few details, and there were times I felt uncomfortable with the way the film went digging for secrets that Maier had worked so hard to keep, in the name of contextualizing her art.

There’s a small Vivian Maier exhibit at the Chicago Public Library this summer, and a few days after I saw the film I went to see her photos there. My visit felt completist — a little extra credit on top of the documentary — but also repentant, as if after watching her life being dissected I needed to shift things back to her terms, let her decide what to put in the frame and what to exclude, and let her hide behind the camera again.

* I was gratified when I looked this up to realize that she was paraphrasing Rilke from Letters to a Young Poet: “If, when you wake up in the morning, you can think of nothing but writing…then you are a writer.”