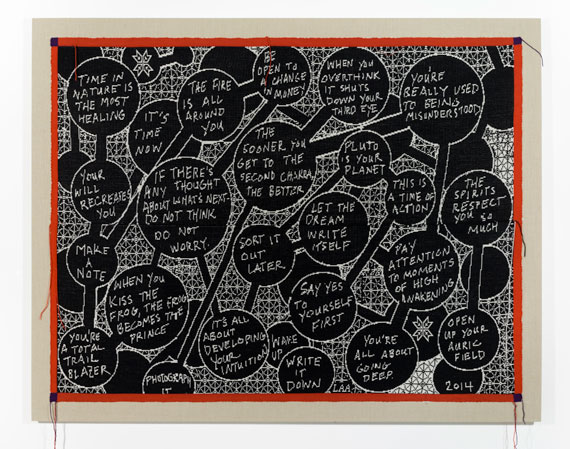

Collection of the artist and Gavlak Gallery, Palm Beach. Copyright Lisa Anne Auerbach. Photograph by Lisa Anne Auerbach.

Paper is a star of the 2014 Whitney Biennial, as one critic put it. This is true as far as it goes, but it doesn’t go far enough. A star of this show — the star, in my opinion — is what’s on the paper. And what’s on the paper is something that has been on a lot of museum and gallery walls lately, as we noted here early this year. That something is the thing we tend to think of as the domain of writers, not artists. That something is words.

The current Whitney Biennial, like its precursors since 1932, tries to answer an impossible question: What is contemporary art in the United States today? Here’s one answer: “Shape-shifting.” That’s the title of the catalog essay by one of this Biennial’s three outside curators, Stuart Comer of the Museum of Modern Art. Comer writes that in making his selections for the show he was “compelled by artists whose work is as hybrid as the significant global, environmental, and technological shifts reshaping the United States.” Nowhere is this crossbreeding more vividly expressed than in one of this Biennial’s staples — what Comer calls “the complex relationship between linguistic and visual forms.”

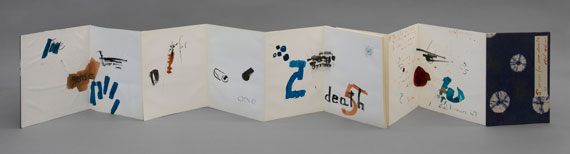

Collection of the artist; courtesy Callicoon Fine Arts, New York

Photograph by Chris Austen

Consider his choice of Etel Adnan, an 89-year-old, Beirut-born, Lebanese-American artist who wrote a highly regarded novel, Sitt Marie-Rose, set during her homeland’s brutal civil war. (She has also written poetry and essays.) A room at the Whitney has several of Adnan’s bright paintings on the walls, looking down on a large vitrine that contains Adnan’s accordion books made of long sheets of folded paper, known as leporellos. One is titled “Funeral March for the First Cosmonaut.” Through a series of watercolor images and blocks of writing, it tells the story of Yuri Gagarin, the first human to journey into outer space. But Adnan’s lovely book is less a celebration of technological achievement than a reflection on creativity and loss. “In the beginning was the white page,” it opens, a chilling fact known to every writer. It goes on to describe Gagarin’s achievement as “a requiem for the sound barrier.” Another leporello, “Five Senses for One Death,” conjures a whimsical world where “every Chevy calls me by my name.” I want to go there.

Consider his choice of Etel Adnan, an 89-year-old, Beirut-born, Lebanese-American artist who wrote a highly regarded novel, Sitt Marie-Rose, set during her homeland’s brutal civil war. (She has also written poetry and essays.) A room at the Whitney has several of Adnan’s bright paintings on the walls, looking down on a large vitrine that contains Adnan’s accordion books made of long sheets of folded paper, known as leporellos. One is titled “Funeral March for the First Cosmonaut.” Through a series of watercolor images and blocks of writing, it tells the story of Yuri Gagarin, the first human to journey into outer space. But Adnan’s lovely book is less a celebration of technological achievement than a reflection on creativity and loss. “In the beginning was the white page,” it opens, a chilling fact known to every writer. It goes on to describe Gagarin’s achievement as “a requiem for the sound barrier.” Another leporello, “Five Senses for One Death,” conjures a whimsical world where “every Chevy calls me by my name.” I want to go there.

In his catalog essay, Comer calls the unfolding pages of the leporellos “a proto-screen, a kind of precursor to the laptops, smartphones, and tablets that increasingly dominate our lives, where the distinction between language and image continues to collapse and multiple surfaces and screens abut and fold into one another.” He notes that Adnan’s life and career are, like this Biennial, about breaking through boundaries. “I find myself gravitating toward artists like Adnan who are working with culture in a freer and more open-minded way — not fighting so much against traditionally established boundaries as ignoring them, unwilling to define themselves as image-makers or writers, painters or sculptors or filmmakers, but working in the interstices of categorical distinctions.”

Many of the 103 participants in the show have chosen to ignore the traditional boundaries between linguistic and visual forms. (Happily, there is also a lot of straight-up painting here, along with sculpture, videos, and performances.) Artists whose works prominently feature written, drawn, painted, printed, or photographed words include David Diao, Carol Jackson, Philip Hanson, Steve Reinke, Karl Haendel, Martin Wong, James Benning, and Allan Sekula. There’s an archive from the works of the boundary-shredding artist/writer/critic Gregory Battcock. Susan Howe has done something William S. Burroughs would have appreciated: She has taken fragments of poems, folklore, criticism, and art history, then cut and rearranged them, printed them on a letterpress, and laid the fragments on facing pages. “The bibliography is the medium,” Howe says on a note card beside the paired pages. “(They) occupy a space between writing and seeing, reading and looking.”

Lisa Anne Auerbach, a Los Angeles-based artist, has stitched together a large woolen assemblage, an ebullient bath of thought bubbles that simply will not shut up. Like some yammering New Age shaman, it peppers the viewer with witticisms and dubious wisdom, such as “You’re All About Going Deep,” “The Sooner You Get To the Second Chakra, the Better,” “Write It All Down,” and “Let the Dream Write Itself.” Auerbach has also produced sweaters that bear messages (“Touch Me” and “Everything I touch turns to sold/Steal this sweater off my back”), as well as a giant zine she calls “American Megazine.” Move over, Barbara Kruger and Jenny Holzer.

Of course these artists’ bewitching use of words is nothing new. Artists have been using words as images for at least the past century (along with single letters, even entire alphabets), an appropriation of the writerly strategy of arriving at meaning through narrative. This Biennial adds to the body of evidence that the practice is accelerating and expanding. I have a theory why this is so. As the practice of writing on paper (everything from telegrams to letters to books to Post-It notes) is increasingly devoured by technology, words on paper are evolving from widespread tools of communication into the rarefied stuff of art. As things recede, they also expand. As a result, words are becoming as legitimate as the more traditional subject matter of painting, drawing, video and sculpture. Running parallel to this trend is a more capacious notion of what constitutes art. Or, as the great critic Holland Cotter put it, this Biennial demonstrates that “not-art” and “maybe-art” deserve a place at the table with “Art.”

Consider the room at the Biennial devoted to the independent publisher Semiotext(e), known for introducing French theory to the U.S. in the 1970s through the writings of Gilles Deleuze, Michel Foucault, Jean Baudrillard, and others. Now based in Los Angeles, it continues to publish works of “theory, fiction, madness, economics, satire, sexuality, science fiction, activism and confession.” On one wall at the Whitney there is a selection of pamphlets produced especially for the Biennial, works by Simone Weil, Gary Indiana, and Chris Kraus, among others. Another wall is plastered with pages of Semitoext(e) books, flyers, and posters of events, including the Schizo-Culture conference at Columbia University in 1975. There’s also a poster for a performance by Semiotext(e) author/performance artist Penny Arcade that presents her succinct CV: “Bitch! Dyke! Faghag! Whore!” For four decades Semiotext(e) has been as much a sensibility as a publishing enterprise, championing the mash-up of high and low that’s now part of the culture’s bedrock. But is all this verbiage “Art”? Absolutely.

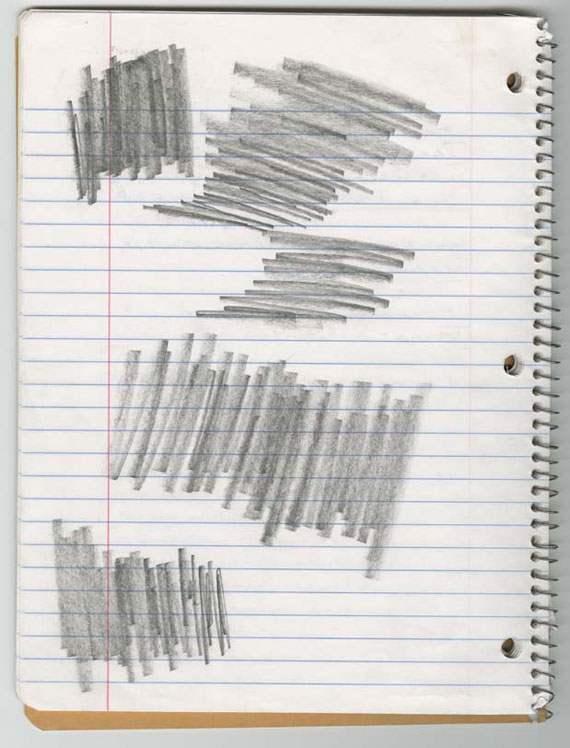

Harry Ransom Center, The University of Texas at Austin. Image used with permission from the David Foster Wallace Literary Trust.

The highlight of this Biennial, for me, is a smallish installation on the top floor, where a sheet of glass serves as a literal window into the mind of David Foster Wallace. After Wallace’s suicide in 2008, Michael Pietsch, publisher of Little Brown, went to Wallace’s studio in California to retrieve a trove of manuscript pages, hard drives, file folders, spiral notebooks, and floppy disks — enough to fill a duffel bag and two Trader Joe’s bags. Pietsch then spent two years stitching the material into the novel we now know as The Pale King.

The highlight of this Biennial, for me, is a smallish installation on the top floor, where a sheet of glass serves as a literal window into the mind of David Foster Wallace. After Wallace’s suicide in 2008, Michael Pietsch, publisher of Little Brown, went to Wallace’s studio in California to retrieve a trove of manuscript pages, hard drives, file folders, spiral notebooks, and floppy disks — enough to fill a duffel bag and two Trader Joe’s bags. Pietsch then spent two years stitching the material into the novel we now know as The Pale King.

On display behind glass at the Whitney is a small but revealing fraction of that mass of material. There’s a spiral notebook with kittens and the words “Cuddly Cuties” on the cover, along with a scrap of paper that contains the word SCENES. Another spiral notebook contains lists of characters’ names, written in Wallace’s spidery script. Another contains references that seem to refer to the novel’s setting, an IRS office in the Midwest: “Bad Organization — many different departments all organized around a central command.” Here’s another way of looking at the IRS: “A ‘bad wheel’ — comprises hubs and spokes but no rim.” Another notebook page contains a group of pencil scrubbings, reminiscent of a Cy Twombly scribble. Or maybe they were an attempt by Wallace to burn off excess energy. Or maybe just sharpen a pencil.

Finally, on the wall above the window, there are two pages from a yellow legal pad that contain handwritten questions for the tennis star Roger Federer, the subject of a long article Wallace wrote for The New York Times in 2006. It became a classic of sports journalism and was included in his posthumous 2012 book of essays, Both Flesh and Not. As it happened, Wallace spent just 20 minutes talking directly with Federer for the article. But the questions reveal how hard Wallace prepared, how hard worked at everything he did, how much he cared. The questions also reveal a disarming directness, a necessary tool for any writer hungry to get all the way under his subject’s skin:

Finally, on the wall above the window, there are two pages from a yellow legal pad that contain handwritten questions for the tennis star Roger Federer, the subject of a long article Wallace wrote for The New York Times in 2006. It became a classic of sports journalism and was included in his posthumous 2012 book of essays, Both Flesh and Not. As it happened, Wallace spent just 20 minutes talking directly with Federer for the article. But the questions reveal how hard Wallace prepared, how hard worked at everything he did, how much he cared. The questions also reveal a disarming directness, a necessary tool for any writer hungry to get all the way under his subject’s skin:

“Is your English good because it was spoken in your home?”

“Does it make you uncomfortable when commentators talk on and on about how good you are?”

“I’ve spent the last couple of days listening to the press and experts talk about you. When you hear people saying that your game is not merely powerful or dominant but beautiful, do you understand this?”

There is also a bit of sly humor here. Wallace, like every writer, sometimes bridled against editorial control. He gives one list of questions a disparaging title: “Non-Journalist Questions: (Q’s the Editors want me to ask).”

Even a few years ago, it would have been unlikely for these marked pieces of paper to make their way onto the walls of a major American museum. Thankfully, things are changing. These pieces of paper are beautiful to look at and beautiful to ponder. They provide nothing less than a glimpse into a brilliant writer’s mind at work. It’s so intimate it almost feels like a trespass. Even so, I recommend it to anyone who’s interested in how ideas become words, how words become literature, and how literature becomes art.