This is the first in a two-part series.

This is the first in a two-part series.

It was Paul Newman. The movie star Paul Newman. Silver hair, dimpled chin, ruddy cheeks, baby blues bright as headlamps. That Paul Newman. I had been rushing home from rehearsals, preoccupied with rewrites I needed to make on my play before it opened for a stage reading at Public Theater downtown, when I nearly ran headlong into him in the hallway of the theater where I was staying. I later learned Newman was waiting for his wife, Joanne Woodward, to finish teaching a class, but I didn’t know that then. All I knew was that on my way upstairs to my room I’d almost run smack into Cool Hand Luke.

But I was 18 years old and in New York for the Young Playwrights Festival, a national contest that produces the work of a few lucky teenage playwrights at off-Broadway theaters. I felt I belonged. Was I not staying at the New Dramatists Theater, a converted church on West 44th Street next door to the Actor’s Studio? Hadn’t Stephen Sondheim, the festival’s founder, just the day before complimented me on my play? So maybe running into iconic movie stars hanging out in the hallway of my building was just the new normal for me. I raised my hand in a casual wave and said simply, “Hey, Paul.”

“Oh hey, how you doing?” he said, waving back, trying to pretend he knew who the hell I was.

With that, I ran upstairs to my room, where instead of starting on the rewrites of my play, I flopped down on the bed to pick up where I’d left off in Moss Hart’s Act One. The ancient paperback copy of Hart’s 1959 memoir had been left, like a theater-world Gideon’s Bible, on the windowsill in my room at New Dramatists. A classic Horatio Alger tale, Act One follows the author’s rise from poverty in the Bronx slums to the height of fame as co-author of the hit comedy Once in a Lifetime, which Hart wrote with legendary wit George S. Kaufman in 1930. Every night for the alternately heady and lonely week I was in New York for my play, I had read myself to sleep with a few pages from Hart’s antic tales of backstage drama and all-night revision sessions on the road to bringing a hit to Broadway.

With that, I ran upstairs to my room, where instead of starting on the rewrites of my play, I flopped down on the bed to pick up where I’d left off in Moss Hart’s Act One. The ancient paperback copy of Hart’s 1959 memoir had been left, like a theater-world Gideon’s Bible, on the windowsill in my room at New Dramatists. A classic Horatio Alger tale, Act One follows the author’s rise from poverty in the Bronx slums to the height of fame as co-author of the hit comedy Once in a Lifetime, which Hart wrote with legendary wit George S. Kaufman in 1930. Every night for the alternately heady and lonely week I was in New York for my play, I had read myself to sleep with a few pages from Hart’s antic tales of backstage drama and all-night revision sessions on the road to bringing a hit to Broadway.

Just a few weeks earlier, in November 1983 — 30 years ago this month — I had picked up the phone in my college dorm and learned that my one-act play, Doggin’ At Dan’s, had been chosen for a staged reading in that year’s Young Playwrights Festival, a contest I had forgotten I’d entered. Few people can genuinely say that a phone call changed their lives. That call changed mine. Before that day, I was an ordinary suburban California kid who was maybe a little overly fond of the hash pipe and the beer bong. When I hung up the phone, I was a writer.

I didn’t win a full production that year, but the next year, another play of mine, The Irishman, was staged at Playwrights Horizons on 42nd Street, with a young Jon Cryer, now the star of the CBS sitcom Two and a Half Men. Only now, all these years later, can I see what a mind-blowing experience the Young Playwrights Festival was for me. Sondheim did, in fact, say nice things about my play. My second year staying at New Dramatists, I partied one night on the roof of the old church with August “Augie” Wilson and the cast of his Broadway show Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom, the first of Wilson’s Pittsburgh Cycle to get a major New York production. And then there was New York itself, then in its most ungovernable Koch-era glory, crack and AIDS raging unchecked, Times Square still its dirty, scary, hookers-and-peep-shows pre-Disney self — all of it wildly exciting and terrifying for a teenage kid from the ’burbs.

I couldn’t know the lasting gravitational pull the Young Playwrights Festival would exert on me that first week at New Dramatists, but I must have had an inkling. I bought my first pack of cigarettes in New York that winter. I also bought a hip flask of whisky at a bodega on Ninth Avenue and knocked back a few shots every night to help me sleep, the first time I had done that. In reality, the Young Playwrights Festival is like any other writing contest, and winning it was as much a matter of luck as anything else, but at the time it felt as if the gods had reached down from writer heaven and picked me — me! — out as a writer, and I needed to get busy proving them right.

It was this quiet panic, the difficulty I was having breathing at this new altitude, that kept bringing me back to Act One night after night. Act One is, after all, the story of an early success in the theater that turns out well. The book ends with Once in a Lifetime opening on Broadway, but that was only the first of many successes in Hart’s career, which include the classic 1930s stage comedies You Can’t Take it With You and The Man Who Came to Dinner that he wrote with Kaufman, as well as solo screenwriting credits for Gentleman’s Agreement and A Star is Born and his role as director of My Fair Lady with Julie Andrews.

Act One offers a fascinating glimpse into the bygone world of 1920s theater, but the book’s centerpiece is Kaufman and Hart’s herculean effort to turn Once in a Lifetime into a hit. In the opening chapters, Hart rises from a lowly theater-office secretary to social director at the Flagler Hotel, one of the famous Borscht Belt summer camps in the Catskills, where generations of Jewish performers from Danny Kaye and Jack Benny to Phyllis Diller and Woody Allen launched their careers. For six long years, Hart spends his summers in the Catskills and his winters directing amateur theater groups at night and writing plays during the day. At last, desperate for a break, he responds to advice from a producer who had rejected one of his dark, serious dramas and tries his hand at comedy. The play, a madcap satire of Hollywood in the early days of talking pictures, is good enough to get the attention of Kaufman, Broadway’s most prolific hitmaker.

The scenes in Kaufman’s writing studio at his Upper East Side brownstone where the two men wrestle with how to turn Hart’s tissue-thin comic premise into a full-length Broadway comedy are priceless — Kaufman, a cold, meticulous craftsman, obsessively washing his hands before starting each new scene; Hart, young and puppy-like, all appetite and restless energy, scarfing entire plates of sandwiches behind Kaufman’s back because he’s so hungry.

But the book takes off when they take the play on the road. In those days, producers opened plays in smaller cities like Atlantic City to give authors time to iron out the kinks before presenting the show to the New York critics. The pace is relentless. The three-hour play runs eight times a week, and every night after the performance the authors stay up until dawn rewriting scenes that fell flat the night before. After a quick nap, they’re up again for an all-day rehearsal so the cast can block out the new scenes and learn the new lines in time for the curtain. And then they do it all over again.

After weeks of murderous toil on the road, and another long hot summer together in Kaufman’s writing studio, they manage to get two of the play’s three acts to work, but the final act stubbornly refuses to be funny. Kaufman, exhausted, throws in the towel, but Hart simply will not quit. With less than a week to go before the New York opening, he sits down for a drink with the play’s producer, Broadway legend Sam Harris, who muses: “It’s a noisy play, kid. One of the noisiest plays I’ve ever been around.”

That’s it! Hart realizes. He and Kaufman have responded to the thinness of the plot by piling on more jokes when what the play needs is a quiet scene that makes the audience care about the characters. He writes a new scene overnight, talks Kaufman into going along with it, and after tossing tens of thousands of dollars of scenery and costumes into a back alley, they open the show at the Music Box Theater on Broadway, where it runs for more than a year and makes Hart rich beyond his wildest dreams.

It’s not hard to understand why I found such solace in Hart’s rags-to-riches story. I don’t come from poverty and I couldn’t write a funny play if my life depended on it, but, like Hart, I was trying to solve a problem faced by all would-be writers: how to hone a garden-variety facility with language and narrative to a professional sharpness that would pierce an audience to the heart. I read a lot of author’s biographies in those years — Hemingway, Fitzgerald, Tennessee Williams, James Baldwin, all my heroes — and the lesson I drew was that I had better get famous fast, preferably by my mid-20s, or the world would take my typewriter away.

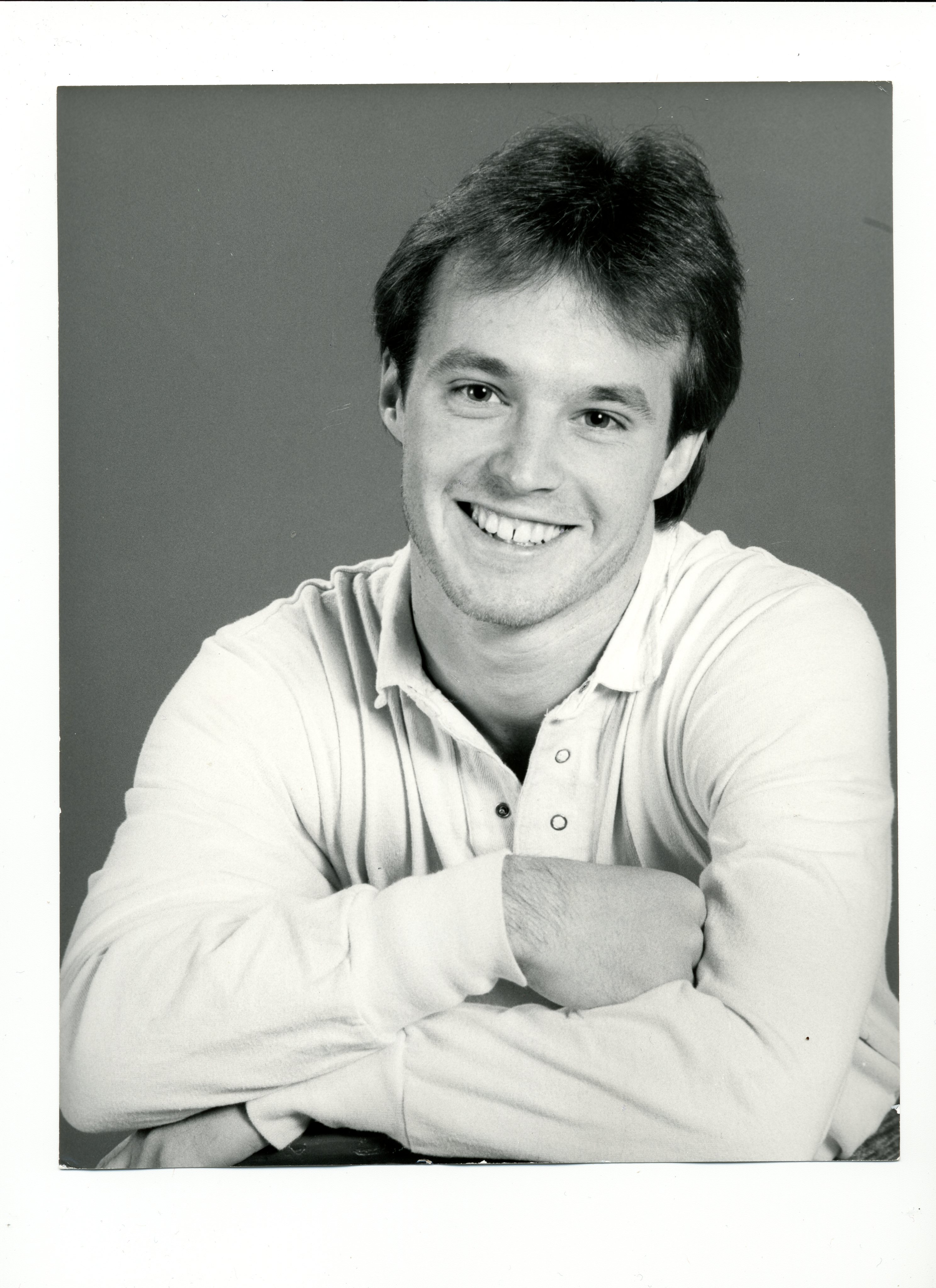

The photograph that accompanies this article shows me at 18, that first, heady winter in New York. Photos taken just a year and a half later when I transferred to NYU, on a scholarship I got thanks in large part to the Young Playwrights Festival, show a different person: hair wild, eyes half-vacant, a weird stoner’s grin on my face. I look like I got in a street fight and then sat sucking on a bong for an hour. Which is essentially how I felt. My sense of self-worth was bound up in a success I had yet to achieve, and the more I wanted it, the more passionately I came to see it as my due, the more impossible it became to achieve it. I stopped eating and started drinking. At first, it was just a beer or two to help me sleep. Then two Budweiser tallboys. Then a 40. Then a six-pack, every night. I walked all over any woman foolish enough to get within striking range, and I wrote and wrote and wrote, each new play more tortured and nonsensical than the one before, until, at last, a full-length play of mine was staged at the Circle Repertory Company in New York.

The photograph that accompanies this article shows me at 18, that first, heady winter in New York. Photos taken just a year and a half later when I transferred to NYU, on a scholarship I got thanks in large part to the Young Playwrights Festival, show a different person: hair wild, eyes half-vacant, a weird stoner’s grin on my face. I look like I got in a street fight and then sat sucking on a bong for an hour. Which is essentially how I felt. My sense of self-worth was bound up in a success I had yet to achieve, and the more I wanted it, the more passionately I came to see it as my due, the more impossible it became to achieve it. I stopped eating and started drinking. At first, it was just a beer or two to help me sleep. Then two Budweiser tallboys. Then a 40. Then a six-pack, every night. I walked all over any woman foolish enough to get within striking range, and I wrote and wrote and wrote, each new play more tortured and nonsensical than the one before, until, at last, a full-length play of mine was staged at the Circle Repertory Company in New York.

Circle Rep no longer exists, but it was then the artistic home of the playwright Lanford Wilson and, in its heyday, it was arguably the best launching pad for theatrical writing talent in the country. Thanks to NYU and the Young Playwrights Festival, I got an internship in the theater’s literary office and joined their Playwright’s Workshop, which staged readings of new plays a couple times a month. That was the forum for my play, which was called, fittingly enough, Down the Garden Path.

The play, loosely based on a true event, was about two guys who get drunk and steal a priceless Monet from a museum in San Francisco. The lead character decides he wants to copy the painting, to discover the source of its genius, which over the course of the play turns into an effort to out-paint Monet — and, well, you can see where this is going. I poured all my anger, all my frustration and panic onto the page, and it played like an hour and a half of a young man standing in front of a mirror saying, “I’m ugly. I hate myself. I want to die.” I remember sitting to one side of the stage watching those smart young playwrights watch my play and seeing its awfulness, its terminal self-involvement, and its tail-chasing ragefulness, reveal itself slowly on their disbelieving faces.

When the lights came up, no one had anything to say. Nothing. They didn’t much like me, anyway, but this — this was more awful than they’d counted on. There was nothing to feel but pity, and I walked out of that room thinking I would never write another play. And in fact, I never did.

Instead, I ran. I skipped my college graduation, worked six months in a Chicago restaurant kitchen, and flew to Australia, which, by my rough calculation, was as far as you could get from New York City where people still spoke English. Two weeks after I arrived, while browsing in a bookshop in the Sydney neighborhood of Paddington, I came across a copy of Act One. I hadn’t thought much about Moss Hart and Once in a Lifetime since that first winter at New Dramatists, but it was like running into an old friend halfway around the world. I sat down on the floor of the bookshop and read the first half of the book in one hungry gulp, and then I came back the next day and finished it.

If I were Moss Hart, I would have gone back to my lodgings that night and started a play that, five years later, would bring me fame and fortune. In fact, I did start writing again, prose this time, a long, painful story about my grandmother’s death, which was the first halfway decent thing I’d written in years. But as soon as those pages were written, the noose tightened again and stayed tight, with only the briefest of respites, for the next decade.

There are so many reasons that happened, but one of them is that I completely misread Act One. To me, the book was about that moment in Sam Harris’s office when Hart realized that the play needed a quiet scene. It was about a genius who went with his gut and won. I remember reading about the six years of writing bad plays, which gave me great comfort in Sydney because it meant that the game wasn’t up, but I still missed the point of those six years, which was that it took him all those years of failure to learn how to hear what Sam Harris said and make use of it.

Thirty years later, I still haven’t published a book. I’m close. I’ve finished a novel and a very smart and talented literary agent is submitting it to New York editors. I think it will eventually sell. It’s a good novel, and I ought to know, having written my share of lousy ones. But here’s what’s more important: I think I finally get Moss Hart’s book. It’s not about inspiration. It’s not even about working insane hours and learning from failure. It’s about never giving up. Moss Hart had talent, an inhuman tolerance for work, and a pair of brass balls, but what set him apart from the thousands of other guys hanging around theater lobbies in the mid-1920s trying to catch a break was that the man was fucking relentless.

I’m no Moss Hart. I can’t work those kinds of hours or take that kind of pressure. So I’ve taken the years Hart spent writing bad plays and stretched them out over decades. I’ve read thousands of books. I have a hard drive full of terrible stories and also some not-so-terrible ones. I have built my life in such a way that my many side jobs still allow me time to write fiction. No great hand reached down from the sky and made me a writer. I made myself one, by writing. So if this book doesn’t sell, or if it sells and nobody reads it, I’ll write another. And another. And another. Until I write a book that feels truly necessary, that people read not because I want them to, but because it gives them some news about the human heart they can’t get any other way. And then what will I do? That’s easy. I’ll start writing another one.

Image Credit: Flickr/brokentrinkets