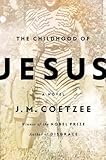

With no mention of the titular character in it at all, critics have been squirming in their seats, unsure of what to think about the title of J.M. Coetzee’s new novel, The Childhood of Jesus. Since its publication in the UK and other English-speaking countries in March, it has become the occasion of many outpourings of critical anxiety. Rare is the occasion when someone like Christopher Tayler in the London Review of Books can feel excited about their confusion; or address it honestly as Leo Robson does in the New Statesman. More common is a scramble to make sense of the thing, like Theo Tait’s ingenious attempt in The Guardian, or the dismissal of its importance in giving the book some other framework for evaluation, as in Justin Cartwright’s otherwise interesting guide to the book for the BBC. And with the publication of the work in the U.S. we can only expect more of the same.

With no mention of the titular character in it at all, critics have been squirming in their seats, unsure of what to think about the title of J.M. Coetzee’s new novel, The Childhood of Jesus. Since its publication in the UK and other English-speaking countries in March, it has become the occasion of many outpourings of critical anxiety. Rare is the occasion when someone like Christopher Tayler in the London Review of Books can feel excited about their confusion; or address it honestly as Leo Robson does in the New Statesman. More common is a scramble to make sense of the thing, like Theo Tait’s ingenious attempt in The Guardian, or the dismissal of its importance in giving the book some other framework for evaluation, as in Justin Cartwright’s otherwise interesting guide to the book for the BBC. And with the publication of the work in the U.S. we can only expect more of the same.

The problem isn’t that the title doesn’t describe what’s in the book. It’s the way it doesn’t. It’s too big a title, too grand. It describes a character who, even if he is not literally related to the character in the book — a boy named David — works on such a larger scale that it wouldn’t even work figuratively. And so even when we can’t find anything meaningful in it, it is hard to believe that Coetzee didn’t mean it to be there. It seems, in other words, indeed serious, in being a little too serious — there’s no letup, no obliqueness in it, no irony that is clear and distinguishable.

The funny thing about it is that Coetzee may well indeed mean what he says, and to be taken to task for this is rather strange: as if once he seems too serious, critics think he can’t be serious at all. And this shows that however petty their reaction has been, the critics are on to something. We know Coetzee as a postmodern writer, a coy writer, playful, always up to something, or trying to be up to something. What we witness in this book is a change of emphasis towards seriousness, a stylistic change, or experiment in changing, which is remarkable to watch.

It’s visible in the straightforwardness of the story itself. The book is about a little boy David and a man old enough to be his grandfather, Simón, arriving in a strange Spanish-speaking land. We don’t know where they are from; we even don’t know their real names, since it was Belstar, the refugee camp where they were, that gave them these. Simón himself, through whose experience we witness most of what happens, doesn’t know anything about the child: details are hazy. “There was a mishap on board the boat during the voyage that might have explained everything,” as Simón puts it. “As a result,” he continues, “his parents are lost, or, more accurately, he is lost.”

The rest of the story is simply David developing under Simón’s care, as they both attempt to start what they call a “new life” together. After a few failed attempts to find the boy’s father and mother, Simón struggles to get a more permanent home for the boy. An old washed-up romantic, but without the confusing animalistic drives of a David Lurie (the hero/villain of Disgrace), he gets it into his head that what the boy needs is a mother. This can be achieved, he thinks, by simply finding one; Simón seems to assume, rather strangely, that a bond like this can be created just by arrangement. Improbably enough, on a hike one day he finds someone willing to be David’s mother, and delivers the boy up to a woman named Inés. But he still watches the boy from afar, and misses him. He folds himself back into the family, doing chores for them and small tasks, and monitors the care of the child, entwining his destiny more and more with his.

The rest of the story is simply David developing under Simón’s care, as they both attempt to start what they call a “new life” together. After a few failed attempts to find the boy’s father and mother, Simón struggles to get a more permanent home for the boy. An old washed-up romantic, but without the confusing animalistic drives of a David Lurie (the hero/villain of Disgrace), he gets it into his head that what the boy needs is a mother. This can be achieved, he thinks, by simply finding one; Simón seems to assume, rather strangely, that a bond like this can be created just by arrangement. Improbably enough, on a hike one day he finds someone willing to be David’s mother, and delivers the boy up to a woman named Inés. But he still watches the boy from afar, and misses him. He folds himself back into the family, doing chores for them and small tasks, and monitors the care of the child, entwining his destiny more and more with his.

There is a strange feeling you can get while reading Coetzee’s work that you merely are hearing a yarn: in other words, that the direct, incredibly precise style is the only thing remarkable about what is simply a straightforward tale. The exact narration of plot borders on bottoming out and becoming the — exquisite, no doubt — chronicling of mere events. This feeling was, in Coetzee’s previous work, always countered by the work’s form breaking up, or turning against itself, which would remind you the precision and exactness was slowly working towards a point: that is, that the work was spare for a reason, that the economy plays generously with the things you are hearing about.

But here we have no postmodern tricks as in Slow Man or Diary of a Bad Year. No strange intertextual references as in Foe. No metafictional scenes like the close of Elizabeth Costello, wherein a strange set of judges in the afterlife ask the titular character, a world-famous author, if fiction itself is really worth anything at all — a fiction in which we hear about the meaning of fiction, and in which the status of the fiction we are reading seems to hang in the balance because of what happens within it. Here we simply have Simón befriending a child and believing in him, as it were, so it is no wonder that this feeling of flatness sticks around, and we think Coetzee has decided to stop with all this beating around the bush, with these sidelong ways of probing the depth of his characters.

But here we have no postmodern tricks as in Slow Man or Diary of a Bad Year. No strange intertextual references as in Foe. No metafictional scenes like the close of Elizabeth Costello, wherein a strange set of judges in the afterlife ask the titular character, a world-famous author, if fiction itself is really worth anything at all — a fiction in which we hear about the meaning of fiction, and in which the status of the fiction we are reading seems to hang in the balance because of what happens within it. Here we simply have Simón befriending a child and believing in him, as it were, so it is no wonder that this feeling of flatness sticks around, and we think Coetzee has decided to stop with all this beating around the bush, with these sidelong ways of probing the depth of his characters.

There are a few tricks still up his sleeve, however. First and foremost there is the pace at which the tale is told, in another instance of that narrative economy which Coetzee has so perfected and which would make anything he writes engrossing. Then, more importantly there is the boy himself. He is, simply, fascinating. Especially in his conceptions and ideas of the world, which Coetzee relates sympathetically and which Simón can’t stop listening to. This despite their childishness, all their petulance and profundity, all their (in a word) contrariness. “Why do I have to speak Spanish all the time?” David asks Simón once. Simón patiently explains:

“We have to speak some language, my boy, unless we want to bark and howl like animals. And if we are going to speak some language, it is best we all speak the same one. Isn’t that reasonable?”

“But why Spanish? I hate Spanish.”

“You don’t hate Spanish. You speak very good Spanish. Your Spanish is better than mine. You are just being contrary. What language do you want to speak?”

“I want to speak my own language.”

“There is no such thing as one’s own language”

“There is! La la fa fa yam ying tu tu.”

Coetzee has David shout things like this often, in the way children do sometimes, where they have been thinking of something by themselves for an hour or so, playing out some internal fantasy of some sort, and suddenly inform you about it as if it was real, and as if it made sense to everyone and was obvious. It happens as David learns to read and talks about Don Quixote as if he were real, as he learns math and talks about numbers as if they had strange properties, as he talks about other people, and their strange characteristics or powers, and in so many other occasions in the novel. And while these fantasies are contrary and counterfactual, they compel. After hearing the boy’s own language, Simón objects:

“That’s just gibberish. It doesn’t mean anything.”

“It does mean something. It means something to me.”

“That may be so but it doesn’t mean anything to me. Language has to mean something to me as well as to you, otherwise it doesn’t count as language.”

In a gesture that he must have picked up from Inés, the boy tosses his head dismissively. “La la fa fa yam ying! Look at me!”

He looks into the boy’s eyes. For the briefest of moments he sees something there. He has no name for it. It is like — that is what occurs to him in the moment. Like a fish that wriggles loose as you try to grasp it. But not like a fish — no, like like a fish. Or like like like a fish. On and on. Then the moment is over, and he is simply standing in silence, staring.

“Did you see?” says the boy.

The key thing about this moment, and about other similar moments, is that Simón did not see, or saw only for a second. But that this reserved and fiercely independent man can so thoroughly commit himself to trying to see, or, at the very least, can so thoroughly commit himself to seeing what it would be like to see, or, at the very very least, can so thoroughly commit himself to seeing what it would be like to see what it would be like to see…this shows Coetzee’s child here is much more than someone relating the wisdom that comes out of the mouths of babes — even perhaps the mouth of a baby Jesus. David is the vehicle for Coetzee’s effort to explore belief’s ability to conquer doubt — more particularly, the doubt of Simón — and of the way fantasies can coax even doubt itself into becoming a form of trust, of faith, of belief.

And as David’s fantasies increasingly disrupt the class in school, and the school threatens, eventually, to kick the boy out and put him in a disciplinary facility for children, Simón has to take this commitment even further, and consider whether he will follow the boy and run off again, away from the authorities, to somewhere else, another new life, or try and stick it out in the town and educate him out of his fictions.

For critics, the biggest problem with Coetzee in his early career was the way his style failed to engage with serious, real-world problems. As critics complained, he lived and wrote in South Africa in the midst of one of the worst crises of the century. Where, in the interesting fables he then fabricated, was anything of the brutal situation around him? Postmodern authors were addressing politics even as they wove interesting tales: Yet Coetzee worked in a sort of neo-Modern arid and ironic style implying that art needed to concentrate on things more ambiguous, sometimes concentrating on colonialism through allegory, representing the colonizers as much as the colonized. He was being contrary, in many ways.

Yet by now Coetzee has published much dealing with animal rights, among other things, and Disgrace dealt directly and provocatively with South African issues. What seemed lacking in the purity of his representations of life has been filled up with a closer and more interesting relationship with the world around us. In the recent edition of his correspondence with Paul Auster, Here and Now, we even find him grumbling about the financial crisis. In this respect, the dust jacket’s claim that The Childhood of Jesus is “allegorical” is misleading, a throwback to an earlier contrarian mood. For now we seem to find Coetzee dealing with a problem different in character: a question about the internal, rather than the external, limits of his work, the limitations of his own style.

Yet by now Coetzee has published much dealing with animal rights, among other things, and Disgrace dealt directly and provocatively with South African issues. What seemed lacking in the purity of his representations of life has been filled up with a closer and more interesting relationship with the world around us. In the recent edition of his correspondence with Paul Auster, Here and Now, we even find him grumbling about the financial crisis. In this respect, the dust jacket’s claim that The Childhood of Jesus is “allegorical” is misleading, a throwback to an earlier contrarian mood. For now we seem to find Coetzee dealing with a problem different in character: a question about the internal, rather than the external, limits of his work, the limitations of his own style.

It is a question of how far irony, self-consciousness, coyness, evasiveness, whimsy, reserve, and simple but efficient avoidance of the commonplace and real, can indeed address the opposite: sincerity, seriousness, truth-telling. While the world can be represented, can it only be played with? Can’t things be believed in? The Childhood of Jesus reminds us again how baffling Coetzee can be, but also that he can be tender, can have, as Frank Kermode once put it, “reserves of feeling that are tragic or even religious.” These are moments where he pretty clearly reminds us that no, we can believe in things, and we do even as we doubt. Play and seriousness have a way of communing together sometimes, with childlike simplicity.