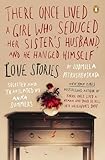

It’s a cliche to note that New York City or London or any other glamorous locale is a character in the books that take place there. But in the case of There Once Lived A Girl Who Seduced Her Sister’s Husband, and He Hanged Himself, a collection of Ludmilla Petrushevskaya’s Soviet-era short stories, Russia may be the only character. The book’s 17 stories are only a few pages each and read so quickly that their plots and characters didn’t make a lasting impression on me. What did is Soviet Russia, and Soviet Russia was the pits.

It’s a cliche to note that New York City or London or any other glamorous locale is a character in the books that take place there. But in the case of There Once Lived A Girl Who Seduced Her Sister’s Husband, and He Hanged Himself, a collection of Ludmilla Petrushevskaya’s Soviet-era short stories, Russia may be the only character. The book’s 17 stories are only a few pages each and read so quickly that their plots and characters didn’t make a lasting impression on me. What did is Soviet Russia, and Soviet Russia was the pits.

The collection’s subtitle, Love Stories, is apt not in the sense that many people end up with love and happiness, but in the sense that the characters — uniformly underpaid, underhoused, underappreciated, and low on groceries — have nothing to hope for but love, the one resource that can’t be rationed. They live in cramped city apartments, assigned to them by the state, with one or two generations of their family, and work in thankless jobs. The most depressing love affairs — emotionless, unrequited, exploitative — shine with promise in these settings.

The stories, as they usually go, start with a cutting introduction of an unattractive young girl:

There once lived a girl who was beloved by her mother but no one else.

What terrible fits she threw, this proud fighter for love! It’s incredible what she went through. Take, for example, her departing husband’s good-bye punch that knocked one of her front teeth inward.

A mother brought her girl to a sanatorium for sickly children and then left. I was that girl.

These inauspicious beginnings are followed by genuinely pathetic possibilities of love. As in, my married coworker is coming over for sex tonight so I asked my mom to absent herself; or, I think I’ll seduce my sister’s husband. Story after story goes by with these unfortunate souls aiming for the lowest rung of happiness and frequently missing. In the rare instance that they succeed, what kind of victory is the lowest rung of happiness? No one ever said reading Russian literature was a picnic.

And yet, Petrushevskaya’s vision is not wholly desolate. If the depressing nature of Soviet life is the book’s first constant, the second is the characters’ romantic optimism, which, under the circumstances, feels like grit. This hope among the ruins, if you like, is patly expressed here:

They were referring, of course, to love, for what else could girls of eighteen talk about? They discussed other things, naturally: books, weather, terrible accidents in the city, injustice and deceit, their childhoods, the constant ache in their feet, and problems at work. But mostly they spoke about friendship and love, tried to analyze their feelings, applied intuition or simply closed their eyes to everything and cried their hearts out, and gradually, in the course of those conversations, acquired a protective layer of hardness that sealed their mouths and left them to fight their grown-up battles alone, wordlessly.

What’s remarkable is not the love they find, but the fact that they’re looking for it. Given their youth, it’s the most natural thing in the world. Given their options (again, the married co-worker or the brother-in-law) it’s either audacious or loony. But they’re looking, is what Petrushevskaya wants us to see. They are indeed proud fighters for love, and when they do attain that low rung of happiness, you can’t help but be happy for them.