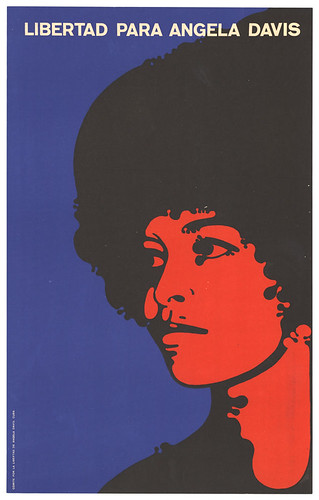

I’ve had a low-grade identity crisis much of my life. I used to be Angela Davis — the real Angela Davis, as far as I knew: blond, blue-eyed, shy, only inwardly radical. Until the day in the summer of 1970, when I was working as a cub reporter for my editor mother at a weekly newspaper and with a laugh she slapped onto my desk a photograph that had just come over the wire: Wanted: Angela Davis. A fierce black woman scowled up at me beneath an enormous Afro. A known communist. 5’8”, 145 lbs. Wanted as an accessory to murder committed by the Black Panthers. My identity and my name had been stolen.

I’ve had a low-grade identity crisis much of my life. I used to be Angela Davis — the real Angela Davis, as far as I knew: blond, blue-eyed, shy, only inwardly radical. Until the day in the summer of 1970, when I was working as a cub reporter for my editor mother at a weekly newspaper and with a laugh she slapped onto my desk a photograph that had just come over the wire: Wanted: Angela Davis. A fierce black woman scowled up at me beneath an enormous Afro. A known communist. 5’8”, 145 lbs. Wanted as an accessory to murder committed by the Black Panthers. My identity and my name had been stolen.

As the revolutionary Angela rose in national prominence, I was subject to laughs and ironic looks when I introduced myself: “Funny, you don’t look like Angela Davis.”

Confusions abounded. When I became a reporter for the Raleigh News and Observer — whose readership includes the conservative eastern part of North Carolina — there were protests to the editor about “the commie” on staff. The “real” Angela came to town, and I was assigned to interview her. Given what I knew about her activities, I found her surprisingly pleasant and low-key, though completely indifferent about the bizarre coincidence of our twin names. (But, by then, she owned the name). Nevertheless, I anticipated the publication of the story with glee: Angela Davis by Angela Davis. This should make some conservative heads spin. And I thought it would set matters straight about my identity, at least in my hometown. It did not.

Not long afterwards I arranged to do a feature on a left-leaning press that was gaining national prominence. When I showed up for the interview, the editor said that he couldn’t talk with me just then, because he was “waiting for Angela Davis.”

This sort of thing has continued for decades. I was offered a writing job at an African- American magazine in Chicago on the strength of “my” name. (The job description was altered once I appeared in the publisher’s office). Later, when I was a professor, even though I had married and added a Gardner to my name by then, I was asked to give a lecture at a national conference on African American literature. (I was tempted to accept.) The editor of my first novel inquired if I might like to change my writing name to Angela Gardner, since Angela Y. Davis (by then the brilliant intellectual writer with an international reputation) had a book coming out from Random House the same season.

I resisted the Angela Gardner option. What if I got divorced? (A prescient thought.) I consider adopting another name. Neither of my grandparents’ surnames — Herbin, Robicheau — though melodious, quite fit.

So I have gone on with a name that is not entirely mine, a name that I sometimes regret when people ask me (still), “Where is she now?” (I have to report though, now that I have a modest reputation as a novelist, I am thrilled when someone says to me: “Not the Angela Davis-Gardner?”)

My happiest discovery, however, has been to realize that when I’m in the process of writing fiction, I have no name. Only my characters exist, and when I live with those characters during years of creation they are as alive to me as most people walking around in the “real” world and I am passionately attached to them. They are mine.

Imagine my surprise then, when one Saturday a few weeks ago, friends called to tell me that my latest novel was going to be featured on NPR’s Weekend Edition. “What happened to the child of Butterfly and Lt. Pinkerton at the close of Puccini’s famous opera Madama Butterfly?” was the lead-in for the story. This described my novel (Butterfly’s Child) and my character — Benji, I had named the child — to perfection.

Imagine my surprise then, when one Saturday a few weeks ago, friends called to tell me that my latest novel was going to be featured on NPR’s Weekend Edition. “What happened to the child of Butterfly and Lt. Pinkerton at the close of Puccini’s famous opera Madama Butterfly?” was the lead-in for the story. This described my novel (Butterfly’s Child) and my character — Benji, I had named the child — to perfection.

I tuned in. The reporter began talking with the writer David Rain, who had just published a debut novel, The Heat of the Sun, about the child of Butterfly and Pinkerton.

I felt like the narrator in Gogol’s story “The Nose” who wakes one day to find that the nose has disappeared from his face. Later he sees the nose walking down the street dressed as a haughty bureaucrat. Part of himself has become a character in his own story and gotten away from him.

In an irony that the metatfictionist Gogol would have appreciated, my character Frank Pinkerton (father of Butterfly’s child) in one scene of my novel attends a performance of the opera Madama Butterfly. Stunned to see his past transgressions — the affair with Butterfly, his caddish behavior — held up to him like a mirror, Pinkerton cries out, “They’ve stolen my life!”

Exactly, Pinkerton. Were you getting even with me? For here was a young man with an Australian accent being interviewed about my characters — including you — as though he had invented them.

Decades ago, when I seemed to be in serene and exclusive possession of the name Angela Davis and I was in graduate school working on an MFA, my teacher, the poet Randall Jarrell, gave me a copy of his new book, The Bat Poet. The gift was in congratulation for an essay I’d written about Nikolai Gogol in Jarrell’s Russian literature class. The bat in the story is moved to poetry as he listens to the mockingbird’s riffs on the melodies of other birds. His question — “Which one’s the mockingbird, which one’s the world?” — is his epiphany, an awareness of the porous boundary between art and reality. That moment is also a comment on the phenomenon of art drawing upon art. The bat is an artist reflecting the artistry of the mockingbird; the thrush and the cardinal and the jay, whose songs the mockingbird imitates, are artists too.

Decades ago, when I seemed to be in serene and exclusive possession of the name Angela Davis and I was in graduate school working on an MFA, my teacher, the poet Randall Jarrell, gave me a copy of his new book, The Bat Poet. The gift was in congratulation for an essay I’d written about Nikolai Gogol in Jarrell’s Russian literature class. The bat in the story is moved to poetry as he listens to the mockingbird’s riffs on the melodies of other birds. His question — “Which one’s the mockingbird, which one’s the world?” — is his epiphany, an awareness of the porous boundary between art and reality. That moment is also a comment on the phenomenon of art drawing upon art. The bat is an artist reflecting the artistry of the mockingbird; the thrush and the cardinal and the jay, whose songs the mockingbird imitates, are artists too.

After the initial shock of hearing about another novel featuring Butterfly’s child, I realized that of course David Rain has as much right to the character Butterfly’s child and his fictional world as I do. Our characters are quite different. But the similarities between the premises of the two novels is a striking example of what Jonathan Lethem discusses in his brilliant essay, “The Ecstasy of Influence:” all writers inevitably plagiarize from the vast world of literature and ideas.

Both Rain and I borrowed our characters from Puccini’s opera. Puccini took his story from playwright David Belasco, who built on the novel of John Luther Long, who was trying to cash in on the popularity of Pierre Loti’s Madame Chrysanthemum.

My Butterfly’s child Benji and Rain’s character Trouble have the same literary DNA — the same father and mother, the same back story. The play Miss Saigon, the film M. Butterfly, and the recent Japanese opera about Butterfly’s child (titled, in English, Butterfly Junior) also share their heritage. All these offspring are testament to the power of the Madame Butterfly myth, which is itself a manifestation of the timeless love-triangle plot.

But please remember, dear reader, that the name of my Butterfly’s child is Benji. He’s blond with a Japanese face (the very embodiment of identity conflict), he has a quite a story to tell, and he’d like to meet you.

And I am the real Angela Davis-Gardner.