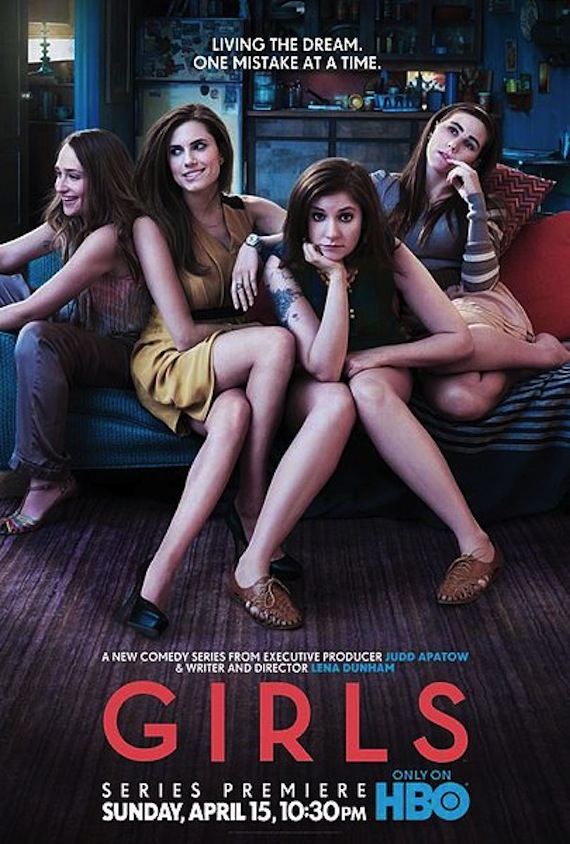

The first moment I saw that one giant word “GIRLS” flash across the screen in all caps, I became utterly, hopelessly enamored of Lena Dunham’s HBO television show. Yes, I know the endless criticisms, both reasonable and totally unreasonable. No matter. The show speaks to me like no other television show currently on air, and I am beyond excited that it is back for a second season on Sunday.

But while Dunham’s lady-centered wry comedy may be singular in today’s television line-up, the world of literature is home to a multitude of books with the same appeal as Girls, books that feature a certain kind of female protagonist (usually one coming of age) or a certain kind of female narrator (pointed, self-deprecating, and ultimately wise). These are books that — like Girls — explore what it is like to be young and hungry — hungry for love and hungry for sex, but most of all, hungry for recognition and hungry for adulthood. Ultimately, the girls in these books, like the girls of Girls, are hungry to become the women they will one day be.

And yes, of course, the girls in question here, both on the show and in these books, are privileged enough that they are not literally hungry. Many of them are also privileged enough to live on their own in New York and to be more concerned with opportunity costs than financial costs. And yes, the girls in these books — like on the television show — are all white. I am not white (or at least I’m only half), but these happen to be the books that have jumped out at me, that made me feel as if something of my own life had been understood and articulated in a way that was both illuminating and reassuring. I welcome your suggestions for other books in the comments.

How Should a Person Be? by Sheila Heti: Many comparisons have been made between Heti’s novel and Girls, the most titillating of which obsess about both projects’ frank depictions of sex and shadows of autobiography. Less titillating but far more important are their shared concerns about the process of becoming an artist and also the intricacies of female friendship. The fictional Sheila and her best friend Margaux ostensibly fall out over a yellow dress, and Hannah and Marnie ostensibly fall out over the rent/Marnie buying a book by Hannah’s nemesis/which one of them is “the wound,” but really, both fights are ultimately about boundaries, both artistic and personal. It’s no surprise that Sheila and Margaux patch things up (though I won’t spoil how), and we have yet to see where things go for Hannah and Marnie, but both brutally honest portrayals do full justice to the complexity of a crumbling friendship, whether it’s eventually resuscitated or not.

How Should a Person Be? by Sheila Heti: Many comparisons have been made between Heti’s novel and Girls, the most titillating of which obsess about both projects’ frank depictions of sex and shadows of autobiography. Less titillating but far more important are their shared concerns about the process of becoming an artist and also the intricacies of female friendship. The fictional Sheila and her best friend Margaux ostensibly fall out over a yellow dress, and Hannah and Marnie ostensibly fall out over the rent/Marnie buying a book by Hannah’s nemesis/which one of them is “the wound,” but really, both fights are ultimately about boundaries, both artistic and personal. It’s no surprise that Sheila and Margaux patch things up (though I won’t spoil how), and we have yet to see where things go for Hannah and Marnie, but both brutally honest portrayals do full justice to the complexity of a crumbling friendship, whether it’s eventually resuscitated or not.

The Fallback Plan by Leigh Stein: After graduating from college (with an oh-so-useful theater degree), 22-year-old Esther Kohler moves back home with her parents in suburban Illinois, where she takes a gig babysitting for the neighbors in order to pay her parents rent on her childhood bedroom. She quickly becomes involved with her charge’s father (shades of Jessa), as well as a Very Handsome friend her own age (complete with awkward — completely, terribly, realistically awkward — sex scene). Stein’s wry voice shines through the entire short novel, especially in the pages involving the Littlest Panda, a creation of Esther’s imagination that she wants to turn into a Chronicles of Narnia-inspired screenplay. There is, of course, more to Esther’s lethargy and indecision than meets the eye, but her (and Stein’s) self-aware take on the self-pitying recession-grad generation is compelling reading even without the eventual reveal about Esther’s backstory.

The Fallback Plan by Leigh Stein: After graduating from college (with an oh-so-useful theater degree), 22-year-old Esther Kohler moves back home with her parents in suburban Illinois, where she takes a gig babysitting for the neighbors in order to pay her parents rent on her childhood bedroom. She quickly becomes involved with her charge’s father (shades of Jessa), as well as a Very Handsome friend her own age (complete with awkward — completely, terribly, realistically awkward — sex scene). Stein’s wry voice shines through the entire short novel, especially in the pages involving the Littlest Panda, a creation of Esther’s imagination that she wants to turn into a Chronicles of Narnia-inspired screenplay. There is, of course, more to Esther’s lethargy and indecision than meets the eye, but her (and Stein’s) self-aware take on the self-pitying recession-grad generation is compelling reading even without the eventual reveal about Esther’s backstory.

The Dud Avocado by Elaine Dundy: The protagonist of Dundy’s 1958 novel is Sally Jay Gorce, a 21-year-old American girl, straight out of college and living abroad for two years on her uncle’s dime. The cult classic was widely praised (by the disparate likes of Ernest Hemingway and Groucho Marx) when it was originally released, and attained cult status anew when NYRB Press reissued it in 2007 (and not just because of the nude figure on the cover). Of all the girls on this list, Gorce seems most like the proto-Girl — a girl who is self-avowedly “hellbent on living,” getting herself into (and out of) escapade after escapade during her time in France. Many of Gorce’s misadventures involve a heavy dose of slapstick, starting on page one with our introduction to our heroine, who is sitting at a Parisian bar having a morning cocktail, wearing an evening dress because all her other clothes are at the cleaners.

The Dud Avocado by Elaine Dundy: The protagonist of Dundy’s 1958 novel is Sally Jay Gorce, a 21-year-old American girl, straight out of college and living abroad for two years on her uncle’s dime. The cult classic was widely praised (by the disparate likes of Ernest Hemingway and Groucho Marx) when it was originally released, and attained cult status anew when NYRB Press reissued it in 2007 (and not just because of the nude figure on the cover). Of all the girls on this list, Gorce seems most like the proto-Girl — a girl who is self-avowedly “hellbent on living,” getting herself into (and out of) escapade after escapade during her time in France. Many of Gorce’s misadventures involve a heavy dose of slapstick, starting on page one with our introduction to our heroine, who is sitting at a Parisian bar having a morning cocktail, wearing an evening dress because all her other clothes are at the cleaners.

The Diary of Anaïs Nin, Volume 1: 1931-1934 by Anaïs Nin: When Hannah’s diary got her into a mess of trouble, she probably took comfort in the tradition of great literary diarists before her, of whom Anaïs Nin is the reigning queen. In Volume One (of the six expurgated adult diaries), Nin talks freely — one might say obsessively — about Henry Miller and his wife June, her psychoanalysis, and her relationship with her father. But you don’t read Nin’s diaries for the plot points so much as the arcs of emotion and insight, as well as the searing descriptions of her friends and their relationships, (sound familiar, Marnie and Charlie?). Still, Nin perhaps has more in common with Jessa than with Hannah, as in this entry, reminiscent of the Jessa-ism that is possibly the most famous line from Season One of Girls: “Psychoanalysis did save me because it allowed the birth of the real me, a most dangerous and painful one for a woman, filled with dangers; for no one has ever loved an adventurous woman as they have loved adventurous men…I may not become a saint, but I am very full and very rich. I cannot install myself anywhere yet; I must climb dizzier heights.” Then again, Jessa would never be caught dead “journaling.”

The Diary of Anaïs Nin, Volume 1: 1931-1934 by Anaïs Nin: When Hannah’s diary got her into a mess of trouble, she probably took comfort in the tradition of great literary diarists before her, of whom Anaïs Nin is the reigning queen. In Volume One (of the six expurgated adult diaries), Nin talks freely — one might say obsessively — about Henry Miller and his wife June, her psychoanalysis, and her relationship with her father. But you don’t read Nin’s diaries for the plot points so much as the arcs of emotion and insight, as well as the searing descriptions of her friends and their relationships, (sound familiar, Marnie and Charlie?). Still, Nin perhaps has more in common with Jessa than with Hannah, as in this entry, reminiscent of the Jessa-ism that is possibly the most famous line from Season One of Girls: “Psychoanalysis did save me because it allowed the birth of the real me, a most dangerous and painful one for a woman, filled with dangers; for no one has ever loved an adventurous woman as they have loved adventurous men…I may not become a saint, but I am very full and very rich. I cannot install myself anywhere yet; I must climb dizzier heights.” Then again, Jessa would never be caught dead “journaling.”

The Lone Pilgrim by Laurie Colwin: In this collection of stories, the women are farther along the path to adulthood than Hannah and her crew — many are married, own homes, have stable careers — but they are no less lost. These are stories about new lovers and ex-lovers and the complexities of romantic love in all its forms, stories in which the women seek love as a form of stability but also rebel against the expectations of a relationship. In a turn that Jessa would appreciate, one of Colwin’s young female characters gets married in order to prove that she’s serious-minded, but meanwhile maintains a constant low-level high throughout the courtship and marriage. Beyond their thematic overlap, the stories are linked by Colwin’s diamond-sharp prose and emotional acuity. At the end of the collection’s eponymous story, Colwin writes of a woman who has married the man she loves and whose life appears to be in place, “Those days were spent in quest — the quest to settle your own life, and now the search has ended. Your imagined happiness is yours…It is yours, but still you are afraid to enter it, wondering what you might find.”

The Lone Pilgrim by Laurie Colwin: In this collection of stories, the women are farther along the path to adulthood than Hannah and her crew — many are married, own homes, have stable careers — but they are no less lost. These are stories about new lovers and ex-lovers and the complexities of romantic love in all its forms, stories in which the women seek love as a form of stability but also rebel against the expectations of a relationship. In a turn that Jessa would appreciate, one of Colwin’s young female characters gets married in order to prove that she’s serious-minded, but meanwhile maintains a constant low-level high throughout the courtship and marriage. Beyond their thematic overlap, the stories are linked by Colwin’s diamond-sharp prose and emotional acuity. At the end of the collection’s eponymous story, Colwin writes of a woman who has married the man she loves and whose life appears to be in place, “Those days were spent in quest — the quest to settle your own life, and now the search has ended. Your imagined happiness is yours…It is yours, but still you are afraid to enter it, wondering what you might find.”

I Was Told There’d Be Cake by Sloane Crosley: Crosley’s first collection of essays covers well-trodden 20-something-living-in-New-York ground, mostly having to do with a privileged class of horrors: the horrible first boss, the horrors of getting locked out of your apartment, the horrors of moving (from one Upper West Side apartment to another), the horrors of being a maid-of-honor. Still, Crosley’s sardonic and self-aware take on those seemingly unremarkable rites of passage elevates them to true moments of insight and recognition. Not to mention laugh-out-loud (or at least smile visibly) lines like: “People are less quick to applaud as you grow older. Life starts out with everyone clapping when you take a poo and goes downhill from there.” And as we know, Dunham loves a good bathroom scene. Hannah Horvath couldn’t have said it better herself.

I Was Told There’d Be Cake by Sloane Crosley: Crosley’s first collection of essays covers well-trodden 20-something-living-in-New-York ground, mostly having to do with a privileged class of horrors: the horrible first boss, the horrors of getting locked out of your apartment, the horrors of moving (from one Upper West Side apartment to another), the horrors of being a maid-of-honor. Still, Crosley’s sardonic and self-aware take on those seemingly unremarkable rites of passage elevates them to true moments of insight and recognition. Not to mention laugh-out-loud (or at least smile visibly) lines like: “People are less quick to applaud as you grow older. Life starts out with everyone clapping when you take a poo and goes downhill from there.” And as we know, Dunham loves a good bathroom scene. Hannah Horvath couldn’t have said it better herself.

The Group by Mary McCarthy: When The Group was first published in 1963, Norman Podhoretz dismissed it as “a trivial lady writer’s novel,” the kind of criticism that has dogged female artists — and has already, unsurprisingly, been hurled at Lena Dunham — throughout time. Of course, McCarthy’s novel, which follows a group of eight female friends after they graduate from Vassar and move to New York City in the 1930s, is anything but trivial. At the time it was published, The Group was considered revolutionary — it was banned in Australia while simultaneously spending two years on The New York Times bestseller list. A full 50 years after its publication (and 80 years after the story’s events), the novel’s satire-tinged account of the women’s lives offers a nuanced portrait of love and sex and birth control, marriage and divorce, childbirth and breastfeeding, professional ambition and thwarted dreams, and the fluctuations of female friendship.

The Group by Mary McCarthy: When The Group was first published in 1963, Norman Podhoretz dismissed it as “a trivial lady writer’s novel,” the kind of criticism that has dogged female artists — and has already, unsurprisingly, been hurled at Lena Dunham — throughout time. Of course, McCarthy’s novel, which follows a group of eight female friends after they graduate from Vassar and move to New York City in the 1930s, is anything but trivial. At the time it was published, The Group was considered revolutionary — it was banned in Australia while simultaneously spending two years on The New York Times bestseller list. A full 50 years after its publication (and 80 years after the story’s events), the novel’s satire-tinged account of the women’s lives offers a nuanced portrait of love and sex and birth control, marriage and divorce, childbirth and breastfeeding, professional ambition and thwarted dreams, and the fluctuations of female friendship.

The Girls’ Guide to Hunting and Fishing by Melissa Bank: This collection of linked short stories centers around Jane Rosenal, who, like so many intelligent young female protagonists, works in publishing in New York City. The collection does not exactly follow Jane’s personal search for love, though her love life figures largely in the stories; instead, the stories act more like a romantic education, as Jane observes and interacts with different forms of love as she makes her way from teenager to young woman to adult. Last in the collection, the title story descends into rom-com territory, though Zosia Mamet might be able to work the same miracle with its one-dimensional material — a discussion of The Rules and a final moral to Be Yourself — as she has with the hilarious but terribly flat character of Shoshanna. Still, Bank’s sprightly prose and sympathetic voice run through all the stories, making for an engaging, enjoyable read.

The Girls’ Guide to Hunting and Fishing by Melissa Bank: This collection of linked short stories centers around Jane Rosenal, who, like so many intelligent young female protagonists, works in publishing in New York City. The collection does not exactly follow Jane’s personal search for love, though her love life figures largely in the stories; instead, the stories act more like a romantic education, as Jane observes and interacts with different forms of love as she makes her way from teenager to young woman to adult. Last in the collection, the title story descends into rom-com territory, though Zosia Mamet might be able to work the same miracle with its one-dimensional material — a discussion of The Rules and a final moral to Be Yourself — as she has with the hilarious but terribly flat character of Shoshanna. Still, Bank’s sprightly prose and sympathetic voice run through all the stories, making for an engaging, enjoyable read.

Emma by Jane Austen: Lena Dunham has said that Clueless ranks among her influences, and there would be no Clueless (and perhaps no Hannah Horvath) without Jane Austen’s original meddlesome, egotistic, incredibly flawed heroine, Emma. While Hollywood would have you read Emma as a straight rom-com — and Emma as an unimpeachable heroine — it’s better read the classic novel with the same lens of dramatic irony that the discerning viewer applies to Girls. Hannah is not supposed to be a character who makes all the right decisions; we root for Hannah, but we do not necessarily agree with her every move. In Emma’s case, the close reader cannot necessarily even root for her by the end; if you pay attention, Emma is revealed to be much closer to the original Mean Girl rather than the perfect innocent portrayed in the movies. Just like Hannah, Emma is clueless; we can only hope that by the end of Girls, Hannah will have grown up more than Austen’s beloved-but-actually-kind-of-terrible protagonist.

Emma by Jane Austen: Lena Dunham has said that Clueless ranks among her influences, and there would be no Clueless (and perhaps no Hannah Horvath) without Jane Austen’s original meddlesome, egotistic, incredibly flawed heroine, Emma. While Hollywood would have you read Emma as a straight rom-com — and Emma as an unimpeachable heroine — it’s better read the classic novel with the same lens of dramatic irony that the discerning viewer applies to Girls. Hannah is not supposed to be a character who makes all the right decisions; we root for Hannah, but we do not necessarily agree with her every move. In Emma’s case, the close reader cannot necessarily even root for her by the end; if you pay attention, Emma is revealed to be much closer to the original Mean Girl rather than the perfect innocent portrayed in the movies. Just like Hannah, Emma is clueless; we can only hope that by the end of Girls, Hannah will have grown up more than Austen’s beloved-but-actually-kind-of-terrible protagonist.

Crazy Salad: Some Things About Women by Nora Ephron: Although a few of the essays in Ephron’s landmark collection are somewhat prohibitively dated (the ones concerning Watergate, in particular, rely on a detailed knowledge of the scandal that is unlikely in 2013), most are as relevant today as they were when Ephron wrote them 40 years ago. The best known in the collection, “A Few Words About Breasts,” tackles standards of female beauty that would ring all-too-true for Hannah (remember that cruel scene in which Jessa and Marnie bond by laughing about how small Hannah’s breasts are?). Ultimately, though, the collection’s real legacy is its examination of the Women’s Movement, a reminder — all-too-relevant in today’s political atmosphere — of the struggle for the gender equality (or at least semblance of it) that many 20-something women have simply grown up with. In the final essay of the collection, Ephron offers a piece of wisdom that might benefit the girls of Girls as they continue on with their belated coming-of-age: “I was no good at all at any of it, no good at being a girl; on the other hand, I am not half-bad at being a woman.”

Crazy Salad: Some Things About Women by Nora Ephron: Although a few of the essays in Ephron’s landmark collection are somewhat prohibitively dated (the ones concerning Watergate, in particular, rely on a detailed knowledge of the scandal that is unlikely in 2013), most are as relevant today as they were when Ephron wrote them 40 years ago. The best known in the collection, “A Few Words About Breasts,” tackles standards of female beauty that would ring all-too-true for Hannah (remember that cruel scene in which Jessa and Marnie bond by laughing about how small Hannah’s breasts are?). Ultimately, though, the collection’s real legacy is its examination of the Women’s Movement, a reminder — all-too-relevant in today’s political atmosphere — of the struggle for the gender equality (or at least semblance of it) that many 20-something women have simply grown up with. In the final essay of the collection, Ephron offers a piece of wisdom that might benefit the girls of Girls as they continue on with their belated coming-of-age: “I was no good at all at any of it, no good at being a girl; on the other hand, I am not half-bad at being a woman.”

Image Credit: Wikipedia