1.

Driving south into Miami-Dade County is less scenic than you might expect. Decades of Floridian sprawl have resulted in long, sun-bleached stretches of asphalt punctuated by industrial supply centers, physical therapy clinics, outlet malls, Waffle Houses, Pollo Tropicals, and strip clubs. The anticipated visuals – palm trees, beaches, flashy hotels, and the ocean – are blocked all along I-95 by tall concrete embankments that keep cars away from oak-less subdivisions called Highland Oaks, Rolling Oaks, or Woodlands. Long are the miles spent enduring such non-views; longer still in bumper-to-bumper traffic.

For this reason, I recommend flying into the city at night. As your plane descends from the West, you can peer out your window. What you’ll see at first is nothing: endless blackness in every direction, a sight so rare in some parts of this country that its effect at first is jarring. Am I over the ocean? You aren’t. This is the Everglades, the swamp so gnarly it dissuaded four centuries of settlers from staying put. It’s the defining geography of South Florida, the subtropical “River of Grass” stretched like a permanent, slow-moving membrane over half the state’s limestone shelf. [To see for yourself, click the “left” arrow a couple times on this map.]

After a few moments, the darkness abruptly gives way to a line of neon city lights, a literal demarcation of where wilderness was beaten back by the Army Corps of Engineers. Now your airplane is a few hundred feet above well-lit and densely populated ground – ground that a mile previous was nothing more than mud and mangrove. From no other vantage point can someone as quickly realize that Miami is a city that shouldn’t be here, an enclave carved out from Mother Nature and cut off from its surroundings. Truly, it’s the Magic City.

Culturally, Miami also exists as a world apart from the rest of its own state, the rest of its own nation. The further south one travels in Florida, the further north one feels politically. After all, it’s in the northern regions where you’ll find Quran-burning pastors, pro-abortion billboards, xenophobes, and megachurches. The north gave us Tim Tebow. By contrast, the southern regions are where international relations matter more than American elections, where most residents actually know the difference between “socialism” and “Communism,” where gay pride is evident, and where you probably won’t get that promotion if you can’t speak Spanish. Early in Tom Wolfe’s new novel Back to Blood, a bout of road rage lays bare this separatist feel. “SPEAK ENGLISH, YOU PATHETIC IDIOT! YOU’RE IN AMERICA NOW!” shouts an exasperated “anglo” who’s just been cut off on the road. “No, mía malhablada puta gorda,” replies her Cuban adversary. “We een Mee-ah-mee now! You een Mee-ah-mee now!”

Culturally, Miami also exists as a world apart from the rest of its own state, the rest of its own nation. The further south one travels in Florida, the further north one feels politically. After all, it’s in the northern regions where you’ll find Quran-burning pastors, pro-abortion billboards, xenophobes, and megachurches. The north gave us Tim Tebow. By contrast, the southern regions are where international relations matter more than American elections, where most residents actually know the difference between “socialism” and “Communism,” where gay pride is evident, and where you probably won’t get that promotion if you can’t speak Spanish. Early in Tom Wolfe’s new novel Back to Blood, a bout of road rage lays bare this separatist feel. “SPEAK ENGLISH, YOU PATHETIC IDIOT! YOU’RE IN AMERICA NOW!” shouts an exasperated “anglo” who’s just been cut off on the road. “No, mía malhablada puta gorda,” replies her Cuban adversary. “We een Mee-ah-mee now! You een Mee-ah-mee now!”

2.

Back to Blood is obsessed with cultural abrasion, with the way different classes and races vie for power in a city whose largest demographic is composed not so much of a single nationality as, instead, confederations of “non-Americans” pitted against an eroding white hegemony. Dionisio Cruz, the city’s fictive Cuban mayor, sums it up nicely:

“Miami is the only city in the world, as far as I can tell — in the world — whose population is more than fifty percent recent immigrants…recent immigrants, immigrants from over the past fifty years…and that’s a hell of a thing, when you think about it. […] I was talking to a woman about this the other day, a Haitian lady, and she says to me, ‘Dio, if you really want to understand Miami, you got to realize one thing first of all. In Miami, everybody hates everybody.’”

Dutifully, Wolfe does his best to display these conflicts. In the novel’s first chapter, we meet our hero, Nestor Camacho, a strapping Cuban cop working as a marine patrolman. On this day, he’s tasked with arresting a Cuban refugee who’s boarded a party yacht in Biscayne Bay. Real federal legislation dictates that Cuban refugees are granted admission and amnesty in the United States if and only if they reach dry land before being captured; if accosted at sea, they’re sent packing. (For Haitians, Nicaraguans, Dominicans, and other groups — all of which are deported no matter how long they’ve been here — this is, justifiably, a touchy source of resentment.)

Unfortunately for Nestor, the arrest becomes a citywide cause célèbre, and the next day he finds himself on the front page of both the English-language Miami Herald (favorably) and the Spanish-language Nuevo Herald (unfavorably). His family is none too pleased. For most Cubans residing in South Florida, there is only one thing more reprehensible than Fidel Castro’s regime: prohibiting escape from it. (Miami’s Cuban demographics have traditionally voted Republican ever since John F. Kennedy’s Bay of Pigs fiasco.) As a result, Nestor’s family and peers, sympathetic with the will to flee their native island, all but disown the young cop and brand him a traidor.

But that’s not all. In the subsequent seven hundred pages — for which, reportedly, Wolfe was paid about $10,000 per — readers get glimpses of many more racial imbroglios. Nestor himself hits another racial flashpoint when a de-contextualized YouTube video emerges of him choking out a black drug dealer. We get glimpses of the love/hate relationship between the Haitian and African-American communities; the way corruption and wealth buy access to the upper echelons of “legitimate” society; the way white social strivers manipulate one another to attain superficial status; and, finally, how Miami exists for the privileged as a Will Smith video and for the poor as anything but.

This is “a book on immigration,” Wolfe told The New York Times in 2008, but that’s not really true. This is a book on belonging, and each character seeks it in a different way. Nestor wants his family to accept the fact that he was merely taking orders on that boat. His ex-girlfriend, Magdalena Otero, a psychiatric nurse who’s dating her upper-crust “anglo” boss, wants to belong anywhere but her hometown of Hialeah. Her boss, Dr. Norman Lewis, wants desperately to belong atop Miami’s money-based status pyramid. John Smith, the whitest white dude ever conceived, wants his boat-shoe-wearing, Yale Eli self to be accepted in the Miami Herald newsroom, where his boss, Edward Topping IV, a fellow Eli, wants nothing more than to belong to the Miami in-crowd of socialites and rich men. The Haitian-born Lantier, a French literature professor at Florida International University — err, “Everglades Global University” — wants badly for his children to belong to any culture except for one that speaks Creole.

3.

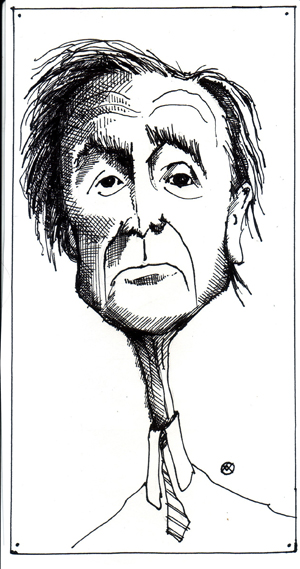

At 81 years old, Wolfe still practices the on-the-ground reporting he’s always prescribed. I was twenty-two months old when he published his Harper’s essay “Stalking the Billion-Footed Beast (PDF),” an entreaty for American novelists to emphasize realism. In The Bonfire of the Vanities, when Wolfe was on top of his game, he incisively depicted a sliver of New York City’s 1980s decadence with the nostalgic accuracy of a Polaroid snapshot. However since then total immersion has proved more and more elusive and his recent novels have been marred by generational misunderstandings, clueless errors, political prejudices, and unfortunate, altogether creepy portrayals of women and youth. This descent is evidenced by his latest imitations of rap lyrics. I Am Charlotte Simmons subjected us to: “Short’s Johnson, he go roamin’ / Homey’s jeans a his is packin’ heat / Inside that cracker jack’s own home, an’ / Bottom lady wants ‘at sweet dark meat.”

At 81 years old, Wolfe still practices the on-the-ground reporting he’s always prescribed. I was twenty-two months old when he published his Harper’s essay “Stalking the Billion-Footed Beast (PDF),” an entreaty for American novelists to emphasize realism. In The Bonfire of the Vanities, when Wolfe was on top of his game, he incisively depicted a sliver of New York City’s 1980s decadence with the nostalgic accuracy of a Polaroid snapshot. However since then total immersion has proved more and more elusive and his recent novels have been marred by generational misunderstandings, clueless errors, political prejudices, and unfortunate, altogether creepy portrayals of women and youth. This descent is evidenced by his latest imitations of rap lyrics. I Am Charlotte Simmons subjected us to: “Short’s Johnson, he go roamin’ / Homey’s jeans a his is packin’ heat / Inside that cracker jack’s own home, an’ / Bottom lady wants ‘at sweet dark meat.”

Fortunately, Wolfe has done some more homework this time. While his rap lyrics haven’t improved (“Caliente! Caliente, baby. / Got plenty fuego in yo caja china / Means you needs a length a Hose put in it, / Ain’ no maybe —”), he has apparently grasped Miami more firmly than he could grasp the American university system. Real places and legitimate commentary are sprinkled throughout the novel like cocaine in a South Beach bathroom. One of Wolfe’s Cuban characters correctly describes Hialeah and its vicinity (Dade County’s most overwhelmingly Latin neighborhoods) as being similar to “Singapore or Taiwan or Hong Kong” in that it’s a sort of free enclave within another country. Other actual Miami institutions are depicted satirically and accurately, such as the trendy and porn-soaked Wynwood Art Walk, the decadent Art Basel festival, and the orgiastic Columbus Day Regatta. (Don’t Google image search that last one if you’re at work.) Wolfe nails the power structure that keeps Miami mired in inertia: the political reality that, just as too many cooks can spoil a broth, too many interest groups can stall a city.

As for his exhortation to emphasize the real over the imagined: Wolfe demonstrates his abilities here as well. In a refreshing bit of contemporary insight – and as a contrast to Jonathan Franzen’s improbably technophobic college students in Freedom – the young people in this novel send one another texts, tweets, and “Instagrams” on their iPhones. Real musicians like Pitbull, Shakira, Rihanna, and, hysterically, LMFAO are name-checked. Somebody said to be getting “white boy wasted” (!!!) has “Wild Ones” as their cell’s ring tone. At one point, a police boat is described as “the Ugly Betty of boatbuilding.”

As for his exhortation to emphasize the real over the imagined: Wolfe demonstrates his abilities here as well. In a refreshing bit of contemporary insight – and as a contrast to Jonathan Franzen’s improbably technophobic college students in Freedom – the young people in this novel send one another texts, tweets, and “Instagrams” on their iPhones. Real musicians like Pitbull, Shakira, Rihanna, and, hysterically, LMFAO are name-checked. Somebody said to be getting “white boy wasted” (!!!) has “Wild Ones” as their cell’s ring tone. At one point, a police boat is described as “the Ugly Betty of boatbuilding.”

However despite these superficial accuracies, the novel is ultimately tripped up by the banal. Compared to their vibrant setting, Wolfe’s characters and plot details are predictable and flat. We learn scarcely anything about Nestor’s motivations and interests, only that he likes to tinker with cell phone ringtones. Magdalena is an enigma: a college-educated psychiatric nurse who doesn’t know the difference between a “logotherapist” and a “pill therapist,” and who doesn’t understand the words “cutting-edge,” “invests,” “extortionist,” or “penthouse,” yet does somehow know the word “czar.” Some characters are introduced (like Edward Topping’s wife) only to be completely forgotten later on. Almost every male character is a hulking, powerful wall of muscle. Almost every female character is a vivacious Latina in tight clothes. One of them even refers to doing the deed as “giving [the guy] some papaya.” (Ugh.)

What’s worse, though, is that the city Wolfe depicts isn’t the full Miami. It’s instead limited by Wolfe’s own perspective: that of a wealthy, conservative anglo. It was T. D. Allman, author of Miami: City of the Future, who wrote that “practically everything everyone says about [Miami], both good and bad, is true.” But is it still true to depict a Miami with only one African-American character? Is it still true if you set only one scene in Overtown, a black neighborhood once known as “Colored Town” but renamed following the construction of the Dolphin Expressway literally “over” the entire area? (That scene, by the way, takes place in a crack house.) Is it still true if you set the novel during the tail end of hurricane season, but fail to mention any rainfall?

4.

It shouldn’t have to be this way. In other American cities, like Burlington or Austin, residents implore one another to “Keep [City Name] Weird.” In South Florida, these calls would be superfluous. Perhaps it’s the lack of a state income tax, or perhaps it’s to be expected from a state founded by hustlers, degenerates, and outlaws, but this place is a veritable treasure chest of weird. Hell, they eat people’s faces here. They overdose on bugs. They alternately molest and cockblock manatees. Wolfe, who loves realism, should’ve been able to uncover these things and more. He should’ve been able to build his novel on the framework of real weird (real interesting) details instead of on things that could take place anywhere: art forgeries, love triangles, and social apprehension. He should’ve been able to give us the Miami you’d encounter if you actually lived here, not the Miami you’d encounter only if your research consisted of Scarface and Grand Theft Auto: Vice City, which is surprising because his guides seem like they were totally capable and qualified. Instead, I suspect Wolfe was caught up in the same trap as the writers of Treme. He seems compelled to check off the boxes of Miami sightseeing without ever delving into what created those sights; he seems to favor the granular detail in place of the overarching narrative, the historical context.

Perhaps one reason for this superficiality is the author’s apparent distraction. Distracted by what? Let this series of rhapsodies – off-putting on their own, but doubly so when you think of the “on-the-ground” reporting that went into this book – answer that question:

Wolfe on women in shorts: “‘Attractive’ barely began to describe the way he felt! Such nice tender legs the two girls had! Such short little short shorts! So short, they could shed them just like that. In an instant they could lay bare their juicy little loins and perfect little cupcake bottoms!”

Wolfe on women in jeans: “Their jeans hugged their declivities fore and aft, entered every crevice, explored every hill and dale of their lower abdomens, climbed their montes veneris.”

Wolfe on women in bathing suits: “Wisps of thong bikini bottoms that didn’t even cover the mons pubis…Tops consisting of two triangles of cloth that hid the nipples but left the rest of the breasts bulging on either side and beckoning, Want more?”

Wolfe on a female stripper: “Her tail is thrust up like a bonobo’s or a chimpanzee’s toward John Smith, offering a full view of the perineum and its forbidden folds, crevices, cracks, clefts, cloven melons, alluring labia, gonophores — the entire fleshy arc.”

The novel’s only actual sex scene: “But then the tips of her breasts became erect on their own, and the flood in her loins washed morals, despair, and all other abstract assessments away in a cloud of some sort of divine cologne of his. Now his big generative jockey was inside her pelvic saddle, riding, riding, riding, and she was eagerly swallowing it swallowing it swallowing it with the saddle’s own lips and maw — all without a word.”

The phrases “lissome legs” and “lubricous loins” are repeated more times than I cared to count. Some of them even take place on my alma mater’s campus, and I shudder at the thought of Wolfe’s gaze stalking the UC Breezeway. I could go on, but you get the idea. It’s disappointing when these bits are so vivid and yet the Miami sun is described as a “big heat lamp in the sky” more than four times.

5.

I dislike savage reviews, and I did not set out to write one about this book, which I genuinely looked forward to reading. I remember loving The Pump-House Gang when I read it in high school. To this day I can recall Wolfe’s description of the door to the Playboy Mansion, how its Latin inscription read, “Si Non Oscillas, Noli Tintinnare” (“if you don’t swing, don’t ring”). But now part of me wonders, were I to reread that book, would I enjoy it as much? Is Wolfe’s writing only appealing to young boys – or perhaps older boys with the minds of young boys? Is there really any shame in liking this style of writing, or is it just a matter of personal taste? I cannot say for certain, but I can say that those seeking a deeper understanding or an accurate depiction of the city of Miami would be better-served by books different from this one.

I dislike savage reviews, and I did not set out to write one about this book, which I genuinely looked forward to reading. I remember loving The Pump-House Gang when I read it in high school. To this day I can recall Wolfe’s description of the door to the Playboy Mansion, how its Latin inscription read, “Si Non Oscillas, Noli Tintinnare” (“if you don’t swing, don’t ring”). But now part of me wonders, were I to reread that book, would I enjoy it as much? Is Wolfe’s writing only appealing to young boys – or perhaps older boys with the minds of young boys? Is there really any shame in liking this style of writing, or is it just a matter of personal taste? I cannot say for certain, but I can say that those seeking a deeper understanding or an accurate depiction of the city of Miami would be better-served by books different from this one.

As a starting point, and because when it comes to Miami, truth is better than fiction, I would recommend John Rothchild’s Up For Grabs, a personal memoir as much as a rollicking trip through South Florida’s outrageous history. Rothchild recounts the way the state’s first American settlers evolved from a cavalcade of land and mineral speculators into mobsters, rumrunners, “pot haulers,” escaped Latin American political players and Cocaine Cowboys. This is the book I wanted to read when I started Wolfe’s novel.

As a starting point, and because when it comes to Miami, truth is better than fiction, I would recommend John Rothchild’s Up For Grabs, a personal memoir as much as a rollicking trip through South Florida’s outrageous history. Rothchild recounts the way the state’s first American settlers evolved from a cavalcade of land and mineral speculators into mobsters, rumrunners, “pot haulers,” escaped Latin American political players and Cocaine Cowboys. This is the book I wanted to read when I started Wolfe’s novel.

I would also recommend, for a more flatly historical perspective, a double shot of Michael Grunwald’s The Swamp and Arva Moore Parks’s Miami: The Magic City. Both books cover the geological and human histories that make South Florida and Miami unique. Neither one dwells on its inhabitants’ “declivities.”

Photo via Wikimedia Commons

Image Credit: Bill Morris/billmorris52@gmail.com