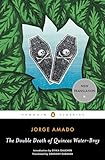

The Brazilian writer Jorge Amado, who died in 2001, would have turned 100 this August. Penguin has released two of his novellas, The Double Death of Quincas Water-Bray and The Discovery of America by the Turks, to coincide with the centennial.

The Brazilian writer Jorge Amado, who died in 2001, would have turned 100 this August. Penguin has released two of his novellas, The Double Death of Quincas Water-Bray and The Discovery of America by the Turks, to coincide with the centennial.

Jorge Amado was well-known in Brazil and internationally. His work was translated into forty-six languages (or as Rivka Galchen writes in her at times oddly snarky introduction to The Double Death of Quincas Water-Bray, translated into “more languages than most Americans know exist.” Because, you know, Americans are dumb.)

He was prolific, highly talented, and prone to political alliances of the kind that are at worst indictments of character, at best appallingly naive. Write-ups of his life tend to make mention of his leftist views without quite mentioning that he was pro-Stalin. I’m very glad I didn’t know before reading The Double Death of Quincas Water-Bray that he’d edited the books section of a pro-Nazi newspaper in the early 1940s, or I doubt that I would have read his work.

Because if you’re the kind of reader who can separate a writer’s politics from a writer’s work, Amado is worth reading. The Double Death of Quincas Water-Bray, originally published in 1961, is a brilliant work. It is a book concerned with perception as much as plot; it is, as Galchen points out, a novel of spin. These are the facts that all parties can agree on: the man known as Quincas Water-Bray — or Quincas Wateryell, in an earlier translation — is found dead one morning in his filthy room of unknown causes, his toe protruding from a dirty sock and a smile on his face. Beyond that, almost everything is in question.

Before he was known as Quincas Water-Bray — enthusiastic drunk, expert gambler, and on friendly terms with every low-life and prostitute around — he was Joaquim Soares da Cunha, respectable citizen and exemplary employee of the State Bureau of Revenue. He remained Joaquim Soares da Cunha until the day when, entirely out of the blue, he spat the word “Vipers!” at his domineering wife and daughter and calmly walked out of the house.

He reemerged as Quincas, transformed from a repressed and somewhat sad office worker into an exuberant drunk, and it was as Quincas that he’d been scandalizing and humiliating his family for some years. They’d been speaking of him in the past tense for a while now. In fact, when his daughter and son-in-law hear the news of his death:

…a sigh of relief arose in unison from the breasts of the couple. From now on it would no longer be the memory of the retired employee of the State Bureau of Revenue overturned and dragged through the mud by the contradictory acts of the tramp he had been transformed into toward the end of his life. The time for a bit of deserved rest had arrived.

He is dressed in a new suit and shoes and laid out in a coffin for a somewhat perfunctory wake. The undertaker didn’t do anything about the smile on the corpse’s face, though, and it seems to his daughter, sitting by the coffin in the candlelit room, that the smile becomes more pronounced as the hours pass. Did she hear him mock her just now? She can’t be sure. She’s exasperated that he’s still exasperating her, even in death. When Quincas’s heartbroken best friends arrive to pay their respects, it begins to seem like it wouldn’t be the worst thing in the world to leave them alone with the coffin, even if they do seem like drunken low-lifes.

It seems to them that his smile broadens when they tell jokes. They prop him up and give him a drink. He has a funny way of drinking — it mostly spills out the side of his mouth — but the man’s got a right to drink however he pleases, they decide, and he seems to be enjoying himself. His family are all blockheads and vipers, he tells them.

Is he alive, or is he dead? There are moments in this very funny, very ghoulish novella when he seems definitely one or the other; other moments when he might somehow be both. He’s roughly the fictional equivalent of Schrödinger’s cat. Did he die once, or twice? This is the question on which his long-suffering family and his friends disagree.

Amado was a master. Everything about the novella is expert. The one discordant note is his insistence, still far too common among non-black authors, in identifying black characters as such while omitting any mention of the races of anyone else. And an argument can be made, of course, that a man born in 1912 was a man born into a different world, but it goes without saying that the fact of his having been a contributor to a Nazi newspaper casts this habit in an unfortunate light.

It seems to me that the novella functions beautifully as a study of freedom. Who was Joaquim Soares da Cunha? What he wasn’t, apparently, was the man he wanted to be. The number of times he died is in question, but he did manage to live two lives, and in the second one he was truly alive.