Could geeking out over a mutually beloved novel surpass even alcohol as the ultimate social ice-breaker? In my three months of solo travel in India, shared literary interests have opened the doors to several new friendships. Quite like the bond formed between travelers on similar journeys, the bond formed around a favorite novel is one of shared immersive experience, usually open to impossibly wide interpretations. When we meet someone else who’s “been there,” there’s a biting urge to know exactly what the other person saw, what scenes remain strongest in her memory, what crucial knowledge or insight was retrieved, and what her experience reveals or changes about our own?

If we try to extend this “traveler’s comparison” to other narrative mediums — television programs, movies, plays — it can often lose some of its steam. Why is this? Relative limitlessness in physical and emotional sensory potential is the privilege and burden of the reader. The book, more so than any other form of narrative media, rings true, more synonymous, with the limitlessness and loneliness to be found while facing the open road or holding a one-way airline ticket to Azerbaijan. In my hypotheses, it is the loneliness quality in particular, physically and intellectually inherent to the act of reading, that lays the bedrock for the powerful social bonding achieved through literature. The limitlessness is critical too, as it promises a bounty of fertile avenues for conversation, but it’s the loneliness of the reader — or, as Rainer Maria Rilke might say, it’s how “two solitudes protect and touch and greet each other” — that assigns to a very special category those friendships formed over books.

Enjoying a good work of literature entails getting lost. Vast and foreign is the journey, and we wouldn’t have it any other way. If the book is good, then the intelligence that guides us through the story will appear many degrees superior to our own. Even in the case of a child narrator like Harper Lee’s Scout Finch, or an impaired one, like Christopher John Francis Boone — the autistic 15-year-old narrator of Mark Haddon’s The Curious Incident Of the Dog in the Night-Time — the narrative intelligences of our books should leave us feeling a bit pressed intellectually, a bit outmatched, amazed ultimately by the talent of the author who brought such an exquisite intelligence to life. It should be our expectation as readers to be transported into a compellingly drawn, but very foreign and unique reality. Our guide, the local aficionado, attempts to help us understand everything we’re taking in, though we’ll inevitably overlook and misunderstand things from time to time, sometimes big, important things. Reading Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow, for me, was an experience similar to that of using one’s brain; I was able to intellectually command perhaps 10 percent of the content at hand. If this was part of Pynchon’s intent for his novel, I commend him for crafting an impressive and very odd reflection of the human condition. Yes, reading is both a richly gratifying and lonely act, at both intellectual and sensory levels, which is why meeting someone with whom we share a favorite book has a way of jump-starting our social batteries, even on our more quiet nights.

Enjoying a good work of literature entails getting lost. Vast and foreign is the journey, and we wouldn’t have it any other way. If the book is good, then the intelligence that guides us through the story will appear many degrees superior to our own. Even in the case of a child narrator like Harper Lee’s Scout Finch, or an impaired one, like Christopher John Francis Boone — the autistic 15-year-old narrator of Mark Haddon’s The Curious Incident Of the Dog in the Night-Time — the narrative intelligences of our books should leave us feeling a bit pressed intellectually, a bit outmatched, amazed ultimately by the talent of the author who brought such an exquisite intelligence to life. It should be our expectation as readers to be transported into a compellingly drawn, but very foreign and unique reality. Our guide, the local aficionado, attempts to help us understand everything we’re taking in, though we’ll inevitably overlook and misunderstand things from time to time, sometimes big, important things. Reading Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow, for me, was an experience similar to that of using one’s brain; I was able to intellectually command perhaps 10 percent of the content at hand. If this was part of Pynchon’s intent for his novel, I commend him for crafting an impressive and very odd reflection of the human condition. Yes, reading is both a richly gratifying and lonely act, at both intellectual and sensory levels, which is why meeting someone with whom we share a favorite book has a way of jump-starting our social batteries, even on our more quiet nights.

Maya Dorn, a 41-year-old copywriter, musician, and avid reader from San Francisco, uses shared literary interests as a litmus test for social compatibility. “Liking the same books is like having the same sense of humor — if you don’t have it in common, it’s going to be hard to bond with someone. You risk ending up with nothing to talk about.” Maya specifically cites Mikhail Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita, as popping up again and again on the fringes of her social circles. Funny she mentioned that title; though I’ve not read The Master and Margarita, it was recommended to me a month prior to meeting Maya, at a café in Goa, where a vacationing Russian day-spa owner — stoned to a point of spare, clear English and silky slow hand gestures — explained to me the premise of Bulgakov’s post-modern “Silver Age” classic. “It’s about different type of prison, a prison of the mind!” The Russian pointed meaningfully at his own head. Sharing such intensely themed, café-table book-talk with a strange Russian proved quite an adventure in itself, with our caffeine jitters occasionally morphing into anachronistic, Cold War-era paranoias of Pynchonesque mirth. He was the first Russian I’d met abroad.

Maya Dorn, a 41-year-old copywriter, musician, and avid reader from San Francisco, uses shared literary interests as a litmus test for social compatibility. “Liking the same books is like having the same sense of humor — if you don’t have it in common, it’s going to be hard to bond with someone. You risk ending up with nothing to talk about.” Maya specifically cites Mikhail Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita, as popping up again and again on the fringes of her social circles. Funny she mentioned that title; though I’ve not read The Master and Margarita, it was recommended to me a month prior to meeting Maya, at a café in Goa, where a vacationing Russian day-spa owner — stoned to a point of spare, clear English and silky slow hand gestures — explained to me the premise of Bulgakov’s post-modern “Silver Age” classic. “It’s about different type of prison, a prison of the mind!” The Russian pointed meaningfully at his own head. Sharing such intensely themed, café-table book-talk with a strange Russian proved quite an adventure in itself, with our caffeine jitters occasionally morphing into anachronistic, Cold War-era paranoias of Pynchonesque mirth. He was the first Russian I’d met abroad.

Currently I’m 100 pages out from finishing Jeffrey Eugenides’ The Marriage Plot, quite a relevant book for this topic, as so many of Eugenides’ principal characters’ social lives are influenced by literature. Clearly Eugenides sees the unique social potency of books as a given fact, something that can be leveraged as a plausible plot-building tool. College seniors, Madeleine Hanna and Leonard Bankhead, sow the early seeds of the novel’s epic romance while discussing various books in a Semiotics 211 seminar. The two of them quietly ally with one other, colluding intellectually against the opinions of the cerebral and pretentious Thurston Meems. Madeleine and Leonard criticize the gratuitous morbidity of Peter Handke’s A Sorrow Beyond Dreams, while Thurston extols the text for its originality. A bit later on in the story (spoiler alert) it is nothing other than a brief, semi-drunken bout of book chatter that opens the door for Madeleine’s unlikely one night stand with the villainous Thurston:

Currently I’m 100 pages out from finishing Jeffrey Eugenides’ The Marriage Plot, quite a relevant book for this topic, as so many of Eugenides’ principal characters’ social lives are influenced by literature. Clearly Eugenides sees the unique social potency of books as a given fact, something that can be leveraged as a plausible plot-building tool. College seniors, Madeleine Hanna and Leonard Bankhead, sow the early seeds of the novel’s epic romance while discussing various books in a Semiotics 211 seminar. The two of them quietly ally with one other, colluding intellectually against the opinions of the cerebral and pretentious Thurston Meems. Madeleine and Leonard criticize the gratuitous morbidity of Peter Handke’s A Sorrow Beyond Dreams, while Thurston extols the text for its originality. A bit later on in the story (spoiler alert) it is nothing other than a brief, semi-drunken bout of book chatter that opens the door for Madeleine’s unlikely one night stand with the villainous Thurston:

‘Which book?’

‘A Lover’s Discourse.’

Thurston squeezed his eyes shut, nodding with pleasure. ‘That’s a great book.’

‘You like it?’ Madeleine said.

‘The thing about that book,’ Thurston said. ‘Is that, ostensibly, it’s a deconstruction of love. It’s supposed to cast a cold eye on the whole romantic enterprise, right? But it reads like a diary.’

‘That’s what my paper’s on!’ Madeleine cried. ‘I deconstructed Barthes’ deconstruction of love.’

In the story-world of The Marriage Plot, literature maintains a power to broker alliances and define enemies. Books are also cited in the mediations of religious and political debate. Books influence career paths, and weigh in profoundly on other critical, life-defining decisions faced by Eugenides’ characters. At one point in the novel, Eugenides finds it perfectly reasonable that nothing other than a positive social experience — three young women bonding at a conference on Victorian literature — would be enough to inspire his protagonist, Madeleine, to pursue a career as a Victorian scholar.

The Marriage Plot isn’t really about books so to speak — I say this despite the title itself being an allusion to the standard plots that recurred throughout the great Victorian-era novels — nevertheless, Eugenides is most comfortable and successful in using the phenomenon of literary community to facilitate settings and move his plots. The success of The Marriage Plot may help illustrate and confirm that the social utility of literature may be by its own right capable of assuring literature’s imminent survival.

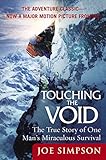

As Eugenides’ novel illustrates, the social reach of literature doesn’t end with discussions of stories and novels. Academic texts and non-fiction contribute peripheral influence to communities of all kinds, even those not squarely centered around literature. Avid reader and rock climber, Joe White, of Leeds, England cites Joe Simpson’s Touching the Void as indispensable to his adventurous social circle. “Though I can’t recall ever forming a particular personal bond over just one book,” Joe says, “being heavily involved in climbing and mountaineering fraternities has led me to form many friendships based around that specific activity, and the literature that surrounds the activity often provides talking points or focal points for the community. Pretty much everyone’s read Touching the Void, I mean, it’s not only relevant to climbing, but it’s an amazing story in its own right.”

As Eugenides’ novel illustrates, the social reach of literature doesn’t end with discussions of stories and novels. Academic texts and non-fiction contribute peripheral influence to communities of all kinds, even those not squarely centered around literature. Avid reader and rock climber, Joe White, of Leeds, England cites Joe Simpson’s Touching the Void as indispensable to his adventurous social circle. “Though I can’t recall ever forming a particular personal bond over just one book,” Joe says, “being heavily involved in climbing and mountaineering fraternities has led me to form many friendships based around that specific activity, and the literature that surrounds the activity often provides talking points or focal points for the community. Pretty much everyone’s read Touching the Void, I mean, it’s not only relevant to climbing, but it’s an amazing story in its own right.”

I recently happened into a brief but enjoyable encounter with the esteemed Joyce Carol Oates. She was promoting her memoir, A Widow’s Story, and was fielding questions from her audience. Amid the 100-plus crowd, I was fortunate to have the opportunity to ask her one:

I recently happened into a brief but enjoyable encounter with the esteemed Joyce Carol Oates. She was promoting her memoir, A Widow’s Story, and was fielding questions from her audience. Amid the 100-plus crowd, I was fortunate to have the opportunity to ask her one:

Ms. Oates, in a recent interview you spoke of the unique type of distress that comes from having one’s work rebuked in a public forum. You cited the experience of your contemporary, Norman Mailer, after having his second novel, Barbary Shore, denounced by the literary critics of the day, making, as Mailer put it, “an outlaw out of him.” But could you speak to the opposite side of this dichotomy — what might you share with us concerning that unique thrill and gratification that comes from producing a superior work of art, a work you know to be beloved by people all over the world. Do those who love your work weigh as heavy on the writer’s mind as those who detract from it?

Oates, took some time in silence to prepare her response.

“Art is a communal experience,” she replied.

As far as directly quoting the writing legend, the exact integrity of my recollections end with that phrase, but I can attest that she expounded for some time on the personal connections to be achieved through these special artifacts, books, these “communal experiences.” But does the act of reading, at a glance, feel in any way communal? Or does it feel, in fact, quite the opposite? Even members of the most ambitious and tightly-knit book clubs tend to do their actual reading in solitude. As such, when the noise of the world becomes occluded by the bestseller between your hands, it’s easy (and perhaps optimal?) to forget that so many others are journeying across this exact same text. You can’t see your companions now, your fellow patrons. They’re nowhere on your radar. You have no idea who they are or that they exist at all. Nevertheless, as you read, your fellow adventurers are out there waiting to meet you, biding their time behind a chance encounter, a well-fated introduction, a tweet, or a blog post, or an otherwise interesting article of prose. You didn’t realize it, but so much mystery, so much anticipation has amassed behind your new friendship, a cosmos-load of potential energy. You didn’t know it — you were too engaged with the mind behind the words — but through all the sentences, the pages, the lovely, lonely hours past, a part of you secretly longed for a flesh-and-blood friend with whom you could share your experience. When you meet your friend, you’ve met an instant confidant. You unburden yourselves on one another, reliving the adventures, revisiting those daunting and glorious experiences you dearly miss, refining and refreshing your perspective in the silver gazing pool of another soul, one that’s triumphed through similar loneliness. Book-bonding is soul-mating, pre-arranged through art, fun-filled and beautiful as a wedding.

Image Credit: Pexels/Min An.