My first reaction on hearing this morning about the death of Christopher Hitchens was not one of shock–obviously, we have all known for some time that this was coming–but one of despondency. What, I immediately thought, are we supposed to do now? Hitchens was, and still is, an indispensable person, a completely necessary man. You didn’t have to agree with him on everything in order to recognise this (he made it more or less impossible, in fact, for any one person to agree with him on everything). Like almost everyone I know, I thought he was very wrong on a number of major issues, but that didn’t stop me wanting to read him, and listen to him talk, and it didn’t stop me from admiring him greatly. The whole point of Hitchens–a major element of his necessity–was that when you disagreed with what he said, you really disagreed, and when you agreed, you wished you had said it yourself. Either way, it was necessary to hear his opinion; the matter in question, whatever it was, hadn’t been fully aired until Hitch had rolled up the sleeves of his off-white linen jacket and got stuck in.

He was the embodiment of the public intellectual, a gifted and prolific writer who was also one of the most gifted and prolific talkers in the English-speaking world. Perhaps the saddest part of his slow dying was the moment, last April, when he lost his voice. His actual physical voice, perhaps even more than his writing, was the substance of his cultural presence. In an essay published in Vanity Fair shortly after this happened to him, he wrote of how an editor at The Guardian once gave him what he saw as an invaluable piece of advice–to “write more like the way you talk.” For most of us, this would be extraordinarily poor counsel, but for Hitchens it turned out to be very useful. Anyone who met him was inevitably struck by the sheer authority and eloquence of his speech, his ability to talk in perfectly formed sentences, with audible parentheses and semi-colons, and (seemingly but not actually) premeditated paragraphs.

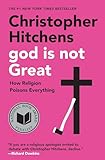

I met him only once. It was June 16th, 2007–Bloomsday–and he was in Dublin to promote his book God is Not Great, which had just hit the top of the New York Times bestsellers list. Back then, I worked for a magazine called Mongrel which was run by a couple of friends of mine, and they called me and asked if I wanted to interview Hitchens. I have never in my life answered a question so vehemently in the affirmative. I went along to his hotel the following morning. Within seconds of his opening the door and sitting me down at a table in the small hotel room, he announced that he needed to use the toilet. Instead of closing the door to the en suite, however, he kept it wide open and talked loudly and authoritatively over the sound of his own micturition. He was enthusing about the Irish novelist Colm Tóibín, who was due to pick him up after the interview and run him out to a party at the home of U2’s manager Paul McGuinness, and whom he claimed was one of the greatest conversationalists he knew, “maybe even better than Mr. Rushdie.” I remember thinking (and later writing) that it took a particularly potent kind of charisma to allow a person to engage in such concentrated namedropping, urinating all the while, and still manage to come across as charming. Hitchens had that kind of charisma. It’s still a source of stinging regret that, when he asked me what I wanted to drink, I opted timidly for a small bottle of white wine from the minibar rather than joining him in the Johnny Walker Black he’d ordered up from room service. It felt a little early in the day for the hard stuff, I think was my rationale. More fool me.

I met him only once. It was June 16th, 2007–Bloomsday–and he was in Dublin to promote his book God is Not Great, which had just hit the top of the New York Times bestsellers list. Back then, I worked for a magazine called Mongrel which was run by a couple of friends of mine, and they called me and asked if I wanted to interview Hitchens. I have never in my life answered a question so vehemently in the affirmative. I went along to his hotel the following morning. Within seconds of his opening the door and sitting me down at a table in the small hotel room, he announced that he needed to use the toilet. Instead of closing the door to the en suite, however, he kept it wide open and talked loudly and authoritatively over the sound of his own micturition. He was enthusing about the Irish novelist Colm Tóibín, who was due to pick him up after the interview and run him out to a party at the home of U2’s manager Paul McGuinness, and whom he claimed was one of the greatest conversationalists he knew, “maybe even better than Mr. Rushdie.” I remember thinking (and later writing) that it took a particularly potent kind of charisma to allow a person to engage in such concentrated namedropping, urinating all the while, and still manage to come across as charming. Hitchens had that kind of charisma. It’s still a source of stinging regret that, when he asked me what I wanted to drink, I opted timidly for a small bottle of white wine from the minibar rather than joining him in the Johnny Walker Black he’d ordered up from room service. It felt a little early in the day for the hard stuff, I think was my rationale. More fool me.

There is no question of anyone coming to occupy anything like the cultural position he created for himself. One of the surest signs of his greatness, for me, is the reaction I have to seeing people trying to bite his contrarian style. I feel sorry for them; it simply can’t be done. Only Hitchens could do what he did. Only Hitchens could write a book-length assault on the reputation of Mother Teresa of Calcutta–denouncing her as, amongst other things, a “lying, thieving Albanian dwarf”–and come out of it looking like the good guy. Only Hitchens would have the audacity, and the intractability, to appear on Fox News the day after the death of the televangelist Jerry Falwell and remark that “if you gave him an enema you could bury him in a matchbox.” We expected a spectacle, of course, and we usually got one, but he was much more than a contrarian exhibitionist. He was a superb writer, and a ferocious advocate of reason, intelligence and intellectual autonomy in a cultural marketplace that is often a rummage-sale of received ideas and half-considered positions. He was also, let’s not forget, an excellent literary critic. He was a sort of combination of John Lydon and Lionel Trilling, and he made that combination seem like a perfectly natural one. As frequently, as bluntly and as eloquently as he wrote about his illness, and as long as we have known that we would eventually lose him, his death still feels like an unexpected loss. It’s too early to measure the extent of it, but we’ll start taking that measurement soon enough; we’ll start as soon as we are compelled to ask, on the occasion of some catastrophic event or monumental political stupidity, “what would Hitchens say about that?”

Jonathan Swift–an Irishman and a cleric with whom this English atheist nonetheless shared some common ground–wrote his own epitaph, perhaps because he didn’t trust anyone else not to mess it up. It’s inscribed, in Latin, on a plaque near his burial site in St. Patrick’s Cathedral in Dublin. W.B. Yeats translated it into English as follows:

Swift has sailed into his rest;

Savage indignation there

Cannot lacerate his breast.

Imitate him if you dare,

World-besotted traveller; he

Served human liberty.

It’s always a sign of a grim juncture when you’re reduced to quoting Yeats, but it seems particularly apt here. Christopher Hitchens has sailed into his rest. Imitate him if you dare.

(Image: Hitches? Hitchens! from allaboutgeorge’s photostream)