Vladimir Nabokov, author of Lolita, Pale Fire, and Speak, Memory, the Russian emigre and American professor, a literary magician in two different languages, left behind a younger brother when he fled Europe to the United States on the eve of World War II. Sergey Nabokov experienced the same confusion of moneyed privilege followed by penurious exile as his famous brother. But Sergey was an artist without an art, a lover of music, ballet, sex, and men. At one point he became an opium addict. He was stranded in Berlin during the last years of the Third Reich.

Novelist Paul Russell has taken this forgotten figure, a footnote in the biography of a twentieth century genius, and brought him back from the shadows in a remarkable novel, The Unreal Life of Sergey Nabokov. It is fiction built on fact, a Nabokovian exploration of the slanted truths of fiction. The title’s echo of Nabokov’s novel about biography, The Real Life of Sebastian Knight, is no accident. Sergey narrates his own story here in a voice that’s a cousin of his brother’s brilliantly freaky ESL English, and not a poor cousin either. The book is an homage to Vladimir Nabokov that also functions as a work of literary criticism (Sergey reads his brother’s early novels with intense familial understanding) and, like the best art, a work of life criticism, too.

Novelist Paul Russell has taken this forgotten figure, a footnote in the biography of a twentieth century genius, and brought him back from the shadows in a remarkable novel, The Unreal Life of Sergey Nabokov. It is fiction built on fact, a Nabokovian exploration of the slanted truths of fiction. The title’s echo of Nabokov’s novel about biography, The Real Life of Sebastian Knight, is no accident. Sergey narrates his own story here in a voice that’s a cousin of his brother’s brilliantly freaky ESL English, and not a poor cousin either. The book is an homage to Vladimir Nabokov that also functions as a work of literary criticism (Sergey reads his brother’s early novels with intense familial understanding) and, like the best art, a work of life criticism, too.

Unreal Life is Russell’s sixth novel. His other books, which include Boys of Life, Sea of Tranquillity, and The Coming Storm, touched on some of the themes he explores here: love, art, beauty, and same-sex desire. But Unreal Life is Russell’s first historical novel, his most ambitious work, and his most epic. He has taken his old themes and put them at the center of the tragedy of modern European history.

Russell lives in an old farmhouse in Rosendale, New York — he teaches literature and creative writing at Vassar College on the other side of the Hudson. I recently spoke with him there about Sergey and Vladimir and the uses and abuses of fiction.

The Millions: When did you first think about writing a novel about Sergey Nabokov?

Paul Russell: My answer should be, “Ever since I wrote my Ph.D. dissertation on Vladimir Nabokov back in the early ‘80s.” I was certainly aware that Nabokov had a gay brother about whom he had very mixed feelings; he writes candidly — albeit briefly — about those mixed feelings in his autobiography Speak, Memory. But it wasn’t until I read Lev Grossman’s essay “The Gay Nabokov” in Salon that I realized here was a subject that had been lying in plain sight for years, and I somehow hadn’t seen it. So I’m very grateful for Lev’s work for making visible certain possibilities for story-telling that should have been obvious; I’m rather embarrassed they had to be pointed out to me like that!

TM: Why a novel? Did you ever consider doing a biography instead?

PR: I don’t really have the patience or talent or temperament to do the kind of research you’d have to do to write a proper biography. It seemed much more congenial to forge Sergey’s memoirs rather than have to track down real life, reluctant sources. I’m a very shy person in many respects; if I can’t do a project while sitting at my desk in my study, chances are I won’t do it. I’m not so good at uncovering facts, but have become quite skilled at dreaming my way toward them. Besides, when I asked Lev if there was other material he’d come across in his extensive detective work but left out of the published essay, he told me he’d put in everything he had. The farther Sergey’s life strayed from his brother’s, the fainter the trail becomes.

TM: This is your first novel about a real person, right? Did you feel trapped or liberated by writing about someone who actually existed?

PR: A little of both. In one sense I had the plot, the basic trajectory of Sergey’s life: his unhappy boyhood in Russia, the family’s flight into exile after the revolution, his Cambridge education, his years in Paris, his Austrian boyfriend, his death in a labor camp outside Hamburg. In another sense, I didn’t have the plot at all — by which I mean the day-to-day details and concerns and preoccupations, all the various eddies that roiled the larger current as it swept him inexorably along toward his fate. I knew about Hermann Thieme, the Austrian, but I had to invent all the other love interests. I knew the famous people Sergey was friends with, but most of our daily lives aren’t lived among famous people. I had the skeleton; I had to invent the organs and musculature and flesh.

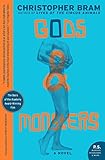

TM: When I wrote Gods and Monsters about movie director James Whale, I first felt freed by having facts to draw upon. Later, however, I became frustrated knowing that no matter what I invented, my protagonist would still have to end up at the bottom of his swimming pool. “Quit complaining,” my agent told me. “Most writers don’t know where their story will go, but you’ve been given a great ending.”

TM: When I wrote Gods and Monsters about movie director James Whale, I first felt freed by having facts to draw upon. Later, however, I became frustrated knowing that no matter what I invented, my protagonist would still have to end up at the bottom of his swimming pool. “Quit complaining,” my agent told me. “Most writers don’t know where their story will go, but you’ve been given a great ending.”

PR: I think it was Hemingway who said, “Follow any life far enough, and it ends badly.” For me, the great looming end was Sergey’s death in a concentration camp. This presented a number of difficulties, especially since, from the beginning, I wanted to write in the first person. I felt it important to give a voice — quite literally — to the silenced brother. To have the fiction of that voice somehow continue into the abyss of the camp seemed not only impossible, but in some way indelicate, even obscene. For a while I toyed with the notion of switching to the third person in order to follow him into the camp; in the end I chose to include a brief Afterword summarizing what happened to him after his arrest by the Gestapo in December, 1943 (he died in January, 1945).

TM: Sergey is not the only historical figure here. You also include Jean Cocteau and Gertrude Stein. What was it like using famous figures fictionally?

PR: Great fun, actually. Stein and Cocteau, paradoxically, intimidated me less than some of the minor characters whom I invented out of thin air. They practically wrote themselves in that their fictional incarnations often quote or at least paraphrase their real life counterparts in dialogue.

TM: What are the legal issues with writing about real people? What are the moral issues?

PR: The legal issues, at least in the US, are simple: you can say anything you want about the dead. The moral issues are, obviously, more complex. In terms of famous people like Cocteau, Stein, or Vladimir Nabokov, I think they’ve ceded any claim to privacy. Sergey presents a different case. He didn’t call attention to himself. He didn’t inscribe his heart on a page for all to see. Some people will feel I shouldn’t have written about Sergey at all, that I’ve stolen something that isn’t mine, that I’ve violated a privacy that, by virtue of the unassuming life he led, he still should retain his right to. Did I struggle with this question a lot? Not really. That may seem profoundly or perversely strange, but in order to write Sergey I had to become Sergey. For instance: I have no religious beliefs whatsoever, but in order to write about Sergey’s conversion to Roman Catholicism, I had enter as deeply and seriously into the mystery of faith as I could. Ballet doesn’t interest me at all, but I had to become a balletomane—or at least try to understand what it is to be a balletomane. Does that sound like madness? It’s the reason I write: to live more abundantly as others than it’s possible to live as myself. Because in writing about Sergey I was also writing about myself — not the self I had previously been, but the expanded self I was forced (or privileged) to become through the very act of imagining Sergey. There’s that line from Rimbaud: “I am someone else.” That’s what I strive for — at least in my writing. Maybe in my life as well.

But back to Sergey, and my violation or consecration of him. I knew from the beginning that, however complicated he might turn out to be as a human being, I wanted to honor the memory of this gay man who was silenced in so many different ways — by his chronic stutter, by his outré sexuality, by the labor camp, and finally by his brother, who failed to mention Sergey’s existence until the third version of Speak, Memory. I think Nabokov, to his credit, eventually regretted that — but it took him a long time to come to terms with his own collusion in that silencing.

TM: What would Sergey have thought of this book?

PR: Part of me suspects he’d have hated it. The Nabokovs were, in general, a reserved lot. But then I remember a letter he wrote to his mother, one of the very few instances of his correspondence that survives. In it he talks eloquently and openly about his love for Hermann Thieme:

There is such light in my soul, my entire life now is such [unprecedented] happiness that I can’t help but tell you about it. There are people who would not understand it, who do not understand such things at all. They would prefer to see me in Paris, barely making it by giving lessons, and at the end, a deeply unhappy creature. There are some talks about my “reputation” etc. But I think that you will understand, understand that all those who do not accept and do not understand my happiness are strangers to me. I wanted to tell you all this and, most importantly, I want you to accept my present life seriously — it is so extraordinary and fairy-like that one has to [think] about it; and the way how many people do it — one can come to a completely wrong conclusion.

So I’d like to think that Sergey would have wanted his story — especially the story of his and Hermann’s love — to be told, and told forthrightly.

Readers will have to make up their own minds.

TM: Your most important famous figure, of course, is Sergey’s brother, Vladimir. What is your history with Nabokov? He is a very important writer for you, right? When did you first discover him? How has your relationship changed over the years?

PR: My first encounter with Nabokov’s work was beautifully Nabokovian. I was a junior in high school, and had checked Pale Fire out of the library. It didn’t have a dust jacket, so I had no warning of what I was getting myself into. As I began to read it, I couldn’t figure out whether John Shade was a real poet, and whether the poem was a real poem (whatever that might mean) and whether I was supposed to take the increasingly erratic commentary by Charles Kinbote (a real scholar?) seriously. I soon put the book down with a shudder — as if I’d stumbled on something monstrous. But as with all things monstrous, I couldn’t stay away for long. The next year, knowing a bit more about it, I read it through, and was delighted, especially by Kinbote’s wild and swooning erotic commentary, with which I completely identified. Then a few months later I happened to come across a description of Kinbote as the novel’s “mad narrator” and was once again thrown for a loop. It hadn’t occurred to me that Kinbote was mad. And of course, now I have enough confidence in my own powers as a reader that I can see that dismissing Kinbote as merely mad misses the point entirely.

PR: My first encounter with Nabokov’s work was beautifully Nabokovian. I was a junior in high school, and had checked Pale Fire out of the library. It didn’t have a dust jacket, so I had no warning of what I was getting myself into. As I began to read it, I couldn’t figure out whether John Shade was a real poet, and whether the poem was a real poem (whatever that might mean) and whether I was supposed to take the increasingly erratic commentary by Charles Kinbote (a real scholar?) seriously. I soon put the book down with a shudder — as if I’d stumbled on something monstrous. But as with all things monstrous, I couldn’t stay away for long. The next year, knowing a bit more about it, I read it through, and was delighted, especially by Kinbote’s wild and swooning erotic commentary, with which I completely identified. Then a few months later I happened to come across a description of Kinbote as the novel’s “mad narrator” and was once again thrown for a loop. It hadn’t occurred to me that Kinbote was mad. And of course, now I have enough confidence in my own powers as a reader that I can see that dismissing Kinbote as merely mad misses the point entirely.

By the time I’d finished college I’d read all Nabokov’s novels, and wrote my honors thesis on him. I was at the same time trying to become a fiction writer by imitating the master. That was of course a terrible idea, though it took me a long time to realize that. In graduate school I intended to write my dissertation on Dickens, but ended up returning to Nabokov — unfinished business, I guess. By the time I completed my dissertation I’d freed myself of his influence — in fact, I never wanted to think about him again, which is the way I imagine many people feel about their dissertation subjects. When I started teaching at Vassar, I realized I didn’t want to do scholarly work but instead write novels, so that’s what I did. Most readers would probably agree that, up till now, my work has been distinctly un-Nabokovian (a reviewer in The Village Voice once described me as a cross between E.M. Forster and Jean Genet!) I do think there’s something poetic in having finally learned how to write like Nabokov — only not the genius Nabokov, but the forgotten Nabokov of modest and dissipated talents.