1.

Poets love the metaphoric possibilities of flowing water. In his book Can Poetry Save the Earth? A Field Guide to Nature Poems, John Felstiner writes of a keen attention to water’s “motion and stillness,” its “changing constancy” in the work of poets like Coleridge, Eliot, William Carlos Williams, A.R. Ammons. And in Robert Frost, who in the poem “West-Running Brook” writes of how the brook of the title is “Flung backward on itself in one white wave,” a wave that “runs counter to itself,” resisting its own forward motion. “It is from that in water we were from,” Frost continues, “Long, long before we were from any creature.”

Poets love the metaphoric possibilities of flowing water. In his book Can Poetry Save the Earth? A Field Guide to Nature Poems, John Felstiner writes of a keen attention to water’s “motion and stillness,” its “changing constancy” in the work of poets like Coleridge, Eliot, William Carlos Williams, A.R. Ammons. And in Robert Frost, who in the poem “West-Running Brook” writes of how the brook of the title is “Flung backward on itself in one white wave,” a wave that “runs counter to itself,” resisting its own forward motion. “It is from that in water we were from,” Frost continues, “Long, long before we were from any creature.”

The earliest river I recall is a muddy branch of the East Fork of the White River, winding through the rural southern Indiana county where I grew up. My friends and I would bike to a rusted iron grate bridge over that branch, the Honeytown Bridge, which rose like some ancient beast from a sea of lowland cornfields. I recall the thrill of aligning my bike tires in the narrow grooves between wider, splintery planks that were there for the tires of cars — flashes of brown water below, a quivering railing on either side.

I drove to find that bridge recently and was sorry to see it replaced by a bland, bleached concrete thing with a flimsy metal guardrail — like one on any roadway, over any river, anywhere. All around it, still those same cornfields. Nothing but corn anywhere you looked. Barely begun sprouts of it on that first day of June — there’d been lots of rain, and farmers were late getting it planted, my father said. These are the fields that I learned, growing up, to call the bottoms. Bottom of the sloping hills, bottom of the agricultural ladder, land that always floods. Fertile land, but volatile, as likely to be underwater as not, less accessible to the big machinery of big farming.

Even a forgotten little river like the White River has its potency. Yet I don’t recall the quiet farmers I knew as a child reaching for ways to describe the river’s power, ascribing human qualities to this sometime foe, this routine flooder of their bottom land. That I’ve found, instead, in the work of poets, like the farmer-poet Robert Frost. In an early poem called “A Brook in the City” (about an urban stream he calls “an immortal force/ No longer needed”), Frost describes this brook as “Staunch[ed] . . . at its source/ With cinder loads dumped down . . . And all for nothing it had ever done/ Except forget to go in fear.”

I love Frost, but I don’t know what to do with another poem of his, a troublesome one, “The Gift Outright.” I’m not sure anyone does, now. And maybe we could ignore it, if it weren’t for the story—trotted out every four years, at the time of every American presidential inauguration — of his choosing to recite it from memory at John Kennedy’s inauguration in 1961, rather than read the new poem he’d composed for the occasion. The wind was ruffling the pages; the sun was in his eyes — so instead of reading his new poem, with his white hair blowing, he intoned this poem that I am unable to interpret as anything but a praise-song for the American notion of manifest destiny:

The land was ours before we were the land’s.

She was our land more than a hundred years

Before we were her people. . . .

And in lines near the poem’s end:

Such as we were we gave ourselves outright

(The deed of gift was many deeds of war)

To the land vaguely realizing westward.

Maybe I could forget about “The Gift Outright” — if it weren’t for that regularly retold story of Kennedy’s inauguration, and if it weren’t for the fact that it’s such a powerful poem, such a clear and potent statement of our longed-for, tormented, permanently ingrained notion of ourselves as Americans, our sense of ourselves as rugged and trailblazing, bursting free from Europe, always edging vaguely westward. Never mind who, or what, else was already here.

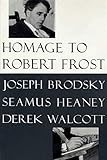

The poem was first published in 1942; Frost recited it, in his old age, in tribute to a “next Augustan age” — youth, revival, exploration, expansion — ushered in by the inauguration of John F. Kennedy. It’s interesting to watch other poets and critics — all admirers of Frost — struggling to make their admiration fit with this poem’s obvious themes (we possessed it before we even got here somehow) and obvious oversights (it belonged to no one else but us). In his chapter in Homage to Robert Frost, Derek Walcott dispenses with “The Gift Outright” early (“No slavery, no colonization of Native Americans, a process of dispossession and then possession, but nothing about the dispossession of others that this destiny demanded”) before devoting his attention to other poems. Similarly, after acknowledging the poem’s connection with the troubling notion of manifest destiny in the introduction to Can Poetry Save the Earth?, John Felstiner never mentions “The Gift Outright” again.

The poem was first published in 1942; Frost recited it, in his old age, in tribute to a “next Augustan age” — youth, revival, exploration, expansion — ushered in by the inauguration of John F. Kennedy. It’s interesting to watch other poets and critics — all admirers of Frost — struggling to make their admiration fit with this poem’s obvious themes (we possessed it before we even got here somehow) and obvious oversights (it belonged to no one else but us). In his chapter in Homage to Robert Frost, Derek Walcott dispenses with “The Gift Outright” early (“No slavery, no colonization of Native Americans, a process of dispossession and then possession, but nothing about the dispossession of others that this destiny demanded”) before devoting his attention to other poems. Similarly, after acknowledging the poem’s connection with the troubling notion of manifest destiny in the introduction to Can Poetry Save the Earth?, John Felstiner never mentions “The Gift Outright” again.

Responding to this poem, a student of mine, a big fan of Frost, insists the poet must have been making heavy use of irony in the poem. It’s hard, I think, for anyone under 30 (maybe even under 40), to imagine the decidedly un-ironic earnestness of the early 1960s. Yet even now, in our more ironic, more knowing, more environmentally conscious twenty-first century, how willing are we to question our right to claim ownership of a piece of land (along a river maybe) — and to do with it what we will?

2.

Why would anyone choose to live on a flood plain anyway?

The first time I recall hearing someone ask this question I was living in New York and working for a textbook publisher. The woman who asked it, a coworker of mine, was trying to express her bewilderment — and irritation — over the fate of residents of the Midwest who’d lost their homes to flooding of the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers in the early 1990s.

This woman was not, as they say, an unintelligent woman. And this was not the first, nor the last, time I would hear someone express the view that where we live is simply a matter of choice. I’ve heard similar questions many times in the last twenty years. Why would anyone choose to live in the path of hurricanes? Or tornadoes? Alongside an earthquake-inducing fault line? Near a bunch of inadequate levees?

Why wouldn’t they just leave?

I did leave the Midwest, in my early twenties. I was someone with the freedom to do so — educated, employable at a time when there was more employment to be had, with help from my parents toward the deposit on my first apartment, in Queens. Looking back, I can see the story that drove me eastward: New York, I thought, was where any Midwesterner who dreamed of being a writer had to go.

Maybe all lovers of poetry let myths and stories drive their life choices. Ten years later I left New York in search of a patch of green, the open air, a house: another deeply etched American myth. That time, vaguely realizing westward, I landed in the Lehigh Valley of eastern Pennsylvania, where two rivers, the Delaware and the Lehigh, converge.

The Lehigh and the Delaware are big boys in the world of rivers — old-time, big-time players, power sources for industry. Or they were. Bethlehem Steel is gone now; near one of its still-standing stacks along the Lehigh River, there is a new casino. According to the Emmaus, Pennsylvania-based Wildlands Conservancy, the 100 mile-long Lehigh River and many of its tributaries are included on the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection’s list of Impaired Waters. The two biggest threats to these waters are abandoned mine drainage to the north and run-off of sediment, fertilizer, pesticides, trash, and other materials in the Lehigh Valley itself.

The Delaware River is one of the only free-flowing rivers in the eastern United States. It runs for nearly 390 miles, beginning in upstate New York, dividing the states of Pennsylvania and New Jersey, and emptying into the Delaware Bay between Cape May, New Jersey and Cape Henlopen, Delaware. According to the environmental advocacy group Delaware Riverkeepers, the river’s watershed makes up only four-tenths of one percent of the continental U.S. land area, but supplies water to five percent of the nation’s population. In 1978 nearly 73 miles of the Upper Delaware were designated as one of the original National Wild and Scenic Rivers.

Thirty-seven miles of the Upper Delaware are now part of the 70,000-acre Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area. Driving east or west along Interstate 80, you’re likely to be stunned by the scenic views from the bridge over the Delaware, wondering if you’re dreaming (how can something this dramatic suddenly appear along an interstate connecting New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania?). This is the Delaware Water Gap — better seen from the Point of Gap Overlook on Route 611 in Pennsylvania — where erosion and glacial uplift formed the Pocono Plateau to the west and the Kittatiny Ridge to the east, with the Delaware River carving a perfect, sinuous S-curve between the two.

Thirty-seven miles of the Upper Delaware are now part of the 70,000-acre Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area. Driving east or west along Interstate 80, you’re likely to be stunned by the scenic views from the bridge over the Delaware, wondering if you’re dreaming (how can something this dramatic suddenly appear along an interstate connecting New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania?). This is the Delaware Water Gap — better seen from the Point of Gap Overlook on Route 611 in Pennsylvania — where erosion and glacial uplift formed the Pocono Plateau to the west and the Kittatiny Ridge to the east, with the Delaware River carving a perfect, sinuous S-curve between the two.

According to the National Park Service, nearly five million people visit the Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area each year. They come to camp, swim, boat, hike, fish, and hunt, or just to admire the landscape from River Road on the Pennsylvania side or Old Mine Road on the New Jersey side. With the aid of a lovely little book called Exploring Delaware Water Gap History, compiled by Susan A. Kopczynski and edited by William G. Dohe, you can take a self-guided driving tour, stopping to gaze on the sites of old resorts, colonial villages, waterfalls, an old copper mine shaft, and abundant — though not always immediately visible — old farmhouses, some of which date back to the eighteenth-century Dutch settlement of the area. Dutch, and then English, Scots-Irish, and German, settlers forced out native peoples, the Lenape and the Minsi, who had dwelled in the area since the retreat of the glaciers.

Most of the old farmhouses are unoccupied now; some provide storage or offices for the National Park Service. Many of them, along with their fertile fields along the river, were seized in the years following the establishment of the Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area in 1965, ten years after a devastating flood. Original plans for the national recreation area called for construction of a dam and a 250 billion-gallon reservoir on the Delaware River at Tocks Island, six miles upstream from the Delaware Water Gap. By the late 1960s, resistance to the dam’s construction would draw broader regional, and even national, attention. “Nix on Tocks” read popular signs and bumper stickers distributed by groups opposing the dam — clearly and deliberately linking the plans for Tocks Island with the federal government.

Many people assume it was the August 1955 flood, which had killed nearly 100 people within the Delaware River Basin, that prompted the Army Corps of Engineers plan to build the Tocks Island dam. But according to Richard C. Albert, author of Damming the Delaware: The Rise and Fall of the Tocks Island Dam, by the time of that flood, a dam on the Delaware was already “largely unfinished business.” Though Pennsylvania and New Jersey had signed an anti-dam treaty nearly 200 years before (to keep the river open for lumber rafts), by the first half of the twentieth century, according to Albert, more than a dozen studies had examined the possibility of dams on the Delaware River for either hydropower or water supply.

Many people assume it was the August 1955 flood, which had killed nearly 100 people within the Delaware River Basin, that prompted the Army Corps of Engineers plan to build the Tocks Island dam. But according to Richard C. Albert, author of Damming the Delaware: The Rise and Fall of the Tocks Island Dam, by the time of that flood, a dam on the Delaware was already “largely unfinished business.” Though Pennsylvania and New Jersey had signed an anti-dam treaty nearly 200 years before (to keep the river open for lumber rafts), by the first half of the twentieth century, according to Albert, more than a dozen studies had examined the possibility of dams on the Delaware River for either hydropower or water supply.

What the flood did precipitate was the involvement of the federal government, and an Army Corps of Engineers comprehensive planning effort that began in 1956 and, by 1961, had called for eleven dams in the Delaware River Basin. The formation of the Delaware River Basin Commission, with representatives from New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Delaware, followed in 1961, the establishment of the Delaware Water Gap Recreational Area in 1965.

Resistance to the dam, and its ultimate defeat, are considered pivotal moments in the nascent American environmental movement. Opponents to the dam could point to many problems — issues with the bearing capacity of the site, for one — but the biggest problem, ultimately, was the ever-growing (and grossly underestimated) cost, at a time when the increasingly unpopular war in Vietnam was draining federal resources. Environmental legislation passed in the late 1960s and early 1970s created further barriers, and in 1975 the Delaware River Basin Commission voted 3 to 1 against immediate construction of the dam (only my home state, Pennsylvania, voted in favor of construction; the federal government abstained). In 1978 the portion of the river where the reservoir would have been became part of the National Wild and Scenic Rivers system, and finally, in 1992, the project was deauthorized by Congress.

That’s a story you can find on the National Park Service web site, though it takes a bit of searching. It’s a story that has not endeared the Park Service — the remaining public face of federal plans, more than forty years ago, to dam the Delaware River and create a giant reservoir — to residents of the Upper Delaware region, on either the Pennsylvania or New Jersey side. Of the reported five million annual visits to the park, most are made by people from farther away, many from New York and Philadelphia and their suburbs. Locals, in general, seem less interested.

One man, whose family were among those who lost their homes in the run-up to the building of the dam and reservoir that were never actually built, voiced lingering resentment in a 2001 article in The Pocono Record. Thirty years after he and his family were evicted from their home north of Shawnee-on-the-Delaware, in Pennsylvania, he reported that he still got “hot under the collar” when he saw a Park Service uniform. He’d rather not hunt along the Delaware anymore, he said.

That Pocono Record article was part of a series by Dave Pierce, who is also at work on a book about the Tocks Island Dam story. Albert’s Damming the Delaware, published in an updated second edition in 2005, is a definitive, and scrupulously detailed, account. But Pierce wants to recount the stories of the people who were evicted, as well as those of some of the strange bedfellows who successfully fought construction of the dam. Among these were local farmers and “housewives” (in the language of the time), but also “hippie squatters” from New York City and elsewhere who moved into abandoned properties on both sides of the river. These squatters arrived after the Army Corps of Engineers, in need of income to support the faltering project, sought renters for the properties in publications like New York’s Village Voice. Even Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas joined a much-publicized 1967 hike to Sunfish Pond in New Jersey — a hike designed to draw attention to the forty-acre glacial pond atop the Kittatiny Mountain that would have been destroyed by the original plans for the dam.

Meanwhile, there’s another regional story Pierce has been working on since around 2003. His investigations into real estate fraud and rampant foreclosures in Monroe County, Pennsylvania — particularly in newly developed communities along Interstates 80 and 380, around twenty miles west and north of the Delaware Water Gap — led to an award-winning series of articles, published in The Pocono Record in 2003 and 2004.

Pierce reports that between the mid-1970s and today, the population of Monroe County, Pennsylvania, home of the Pocono Mountains, grew from 40,000 to 165,000. In April 2004, well before the mortgage crisis became an item of national interest in the U.S., New York Times writers Michael Moss and Andrew Jacobs reported that in the preceding decade, foreclosure proceedings were brought against 5,700 homes in Monroe County. That was one in five of all mortgaged homes.

Pierce, Moss, Jacobs, Matt Birkbeck of the Lehigh Valley, PA Morning Call, and other reporters have all recounted the tales of unscrupulous developers and financiers who lured first-time home buyers — particularly middle-income minority buyers from New York City — to Monroe County with promises of green lawns, stunning views, and gated communities in the beautiful Pocono Mountains. All for less than half the price of a home in nearer suburbs in New York or New Jersey. Never mind that that unbelievably low price was probably inflated a good twenty-five percent over the home’s actual market value. And that its buyer was, often, rushed into a decision on a one-day visit from New York, and also, possibly, pressured to “bump up” his or her income or conceal a bad credit record.

These stories don’t really end — sagas of miserable commutes (I-80 runs directly from New York City to Monroe County, but the Poconos are 100 miles away, and the long-promised rail system shows no sign of materializing); of higher than promised property taxes and hidden fees; of shoddily constructed houses and improperly documented lots; of overcrowded schools and children who are home alone for hours while their parents are at work in New York; of racial tensions in a county that has undergone a demographic sea change in the last twenty years; and ultimately, in many cases, of painful losses of homes, foreclosures, evictions.

One Pocono-area builder, Gene Percudani, launched an advertising campaign in New York that rings with hollow irony now. “Why Rent?” asked his billboards and television ads, which counterposed a gang- and gun-infested New York City with bucolic green lawns and sparkling new homes in the Poconos. “Our goal is homeownership for you and your family. Every American wants it; every American deserves it.”

One of several problems with Percudani’s promises: He was both the builder and the loan broker for his homes. He also hired the appraiser who assessed his homes’ values. These were things that the mortgage unit of Chase Manhattan — the bank Percudani worked with — somehow overlooked.

3.

The land was ours before we were the land’s . . . . We can try to keep realizing westward, but unfortunately, some things are simply finite. Would that the ownership of property — of land, of moving water — were as simple as what Gene Percudani’s “Why Rent?” ads or political rhetoric about home ownership imply. But, as legal scholar Eric Freyfogle writes in The Land We Share: Private Property and the Common Good, private land is understood differently in the realms of law and culture than it is in the “real world of nature”: “Nature is an interconnected whole, one parcel fully linked with the next. Even a seemingly slight action on one tract of land can trigger far-spreading ecological ripples.” One land owner’s use of land — agricultural, industrial, recreational — inevitably affects another land owner’s comfort, pleasure, possibility of profit.

The land was ours before we were the land’s . . . . We can try to keep realizing westward, but unfortunately, some things are simply finite. Would that the ownership of property — of land, of moving water — were as simple as what Gene Percudani’s “Why Rent?” ads or political rhetoric about home ownership imply. But, as legal scholar Eric Freyfogle writes in The Land We Share: Private Property and the Common Good, private land is understood differently in the realms of law and culture than it is in the “real world of nature”: “Nature is an interconnected whole, one parcel fully linked with the next. Even a seemingly slight action on one tract of land can trigger far-spreading ecological ripples.” One land owner’s use of land — agricultural, industrial, recreational — inevitably affects another land owner’s comfort, pleasure, possibility of profit.

A new struggle over land and water in the Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area emerged in 2010, when Pennsylvania Power and Light Electric Utilities and New Jersey Public Service Electric both received state approval (pending environmental permits) to begin building a 500-kilovolt power line through the park. The 100-mile, two-state line would span the river and would require the erection of 200-foot-high towers in the middle of the park. Besides marring the landscape, opponents contend that construction of the line could contaminate groundwater.

To the south, at the other end of the river, a coalition of environmental organizations battled Army Corps of Engineers plans to deepen the Delaware River’s main navigation channel from a depth of 40 feet to 45 feet — a plan that the Delaware Riverkeepers contend threatens the drinking water of residents of Philadelphia and southern New Jersey, as well as marsh and wetland habitats of many fish and birds.

And in June 2010, the Upper Delaware River was #1 on the list of “America’s Most Endangered Rivers,” compiled each year by American Rivers, a conservation organization founded in 1973. The greatest threat to the Upper Delaware, according to the American Rivers web site, was the location of both the river and its watershed over the geological formation known as the Marcellus Shale. Writer Sandra Steingraber (author of Living Downstream), filmmaker Josh Fox (maker of Gasland), and others have argued that the process of extracting natural gas from the Marcellus Shale (hydraulic fracturing, or “fracking”) poses immeasurable environmental threats to groundwater. Multinational energy corporations have already acquired drilling rights to tracts of land atop the extensive Marcellus Shale, which covers large portions of New York, Pennsylvania, West Virginia, and Ohio. According to American Rivers, two companies alone, Chesapeake Appalachia and Statoil, plan to develop 13,500 to 17,000 gas wells in the Upper Delaware River region in the next twenty years. On this year’s list of Most Endangered Rivers, the Upper Delaware was replaced by the Susquehanna, which runs through New York, Pennsylvania, and Maryland. The greatest threat to the Susquehanna, according to the American Rivers web site, is natural gas extraction. At risk is clean drinking water.

And in June 2010, the Upper Delaware River was #1 on the list of “America’s Most Endangered Rivers,” compiled each year by American Rivers, a conservation organization founded in 1973. The greatest threat to the Upper Delaware, according to the American Rivers web site, was the location of both the river and its watershed over the geological formation known as the Marcellus Shale. Writer Sandra Steingraber (author of Living Downstream), filmmaker Josh Fox (maker of Gasland), and others have argued that the process of extracting natural gas from the Marcellus Shale (hydraulic fracturing, or “fracking”) poses immeasurable environmental threats to groundwater. Multinational energy corporations have already acquired drilling rights to tracts of land atop the extensive Marcellus Shale, which covers large portions of New York, Pennsylvania, West Virginia, and Ohio. According to American Rivers, two companies alone, Chesapeake Appalachia and Statoil, plan to develop 13,500 to 17,000 gas wells in the Upper Delaware River region in the next twenty years. On this year’s list of Most Endangered Rivers, the Upper Delaware was replaced by the Susquehanna, which runs through New York, Pennsylvania, and Maryland. The greatest threat to the Susquehanna, according to the American Rivers web site, is natural gas extraction. At risk is clean drinking water.

4.

Meanwhile, most of those evacuated farmhouses on both sides of the Upper Delaware River, the ones you can see on your driving tour through the Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area, are languishing. The Parks Service does sponsor a leasing program, whereby farm fields in the Upper Delaware Valley are rented by farmers. This part of the program has been “very successful,” according to a Parks Service spokesperson; the leasing of historic structures on the park property has been less so.

Though long-term leases of twenty to thirty years were once available, in recent years the program has shifted to competitive, three- to five-year leases. To inquire about a property, you have to first contact the Parks Service in writing. Once you’ve seen a property, if you’re interested in going further, you must submit a detailed proposal outlining your resources and your plans for the property. But as the Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area General Information on Park Leasing Program guidelines specify, “None of the buildings are ready for immediate occupancy. Most will require extensive rehabilitation and high investments of time and money on your part — several hundred thousand dollars at the very least. Grants and government funds are not available.” Not surprisingly, few people get to the proposal-writing stage.

“It’s sad,” a Parks Service employee I spoke with told me. “But we maintain the land, and preserve the land for future generations. . . . We do what we can with the funds and the personnel that we have.” The Parks Service has no funds for preserving historic buildings, she says. Their inheritance of these historic structures was, essentially, an accident.

Twenty miles to the northwest, other, newer homes — foreclosed ones — also stand vacant, and beleaguered mortgage holders continue their endless battles with developers (like the giant Toll Brothers Developers, recently known, in the Poconos, as Toll and Big Ridge Developers), who simply form new companies or change their names and move on. In 1999, Al Wilson, a one-time deputy sheriff in Green County, Alabama and then an employee of the New York City Mayor’s Office and the Board of Education, bought a home in Tunkhannock Township, Pennsylvania, for $195,000. After reading a series of articles by Matt Birkbeck, then at the Pocono Record, reporting on allegations of inflated appraisals and other questionable real estate practices, he sought an independent appraisal and learned that his home was actually worth $145,000 to $150,000. Two years later, embroiled in his own tangled legal struggles, Wilson helped found the Pocono Homeowners Defense Association. The group organized rallies in front of the Monroe County Courthouse in Stroudsburg, the Capitol rotunda in Harrisburg, and F.B.I. headquarters in Washington. Quoted in Moss and Jacobs’ April 2004 New York Times article, Wilson summed up the situation neatly: “It’s like the Wild West out here.” Not, presumably, the wide-open west Frost envisioned in “The Gift Outright.”

5.

“Cut the bank for the fill,” begins William Carlos Williams’ “The Defective Record,” a poem from the 1930s. “Dump sand / pumped out of the river / into the old swale.”

“Level it down,” the poem continues at its end,

. . . to build a house

on to build a

house on to build a house on

to build a house

on to build a house on to . . .

I’ve tried to track down the origin of “homeownership” as a single word. I believe it must be as recent as 1994, when President Bill Clinton directed HUD Secretary Henry Cisneros to launch a National Homeownership Strategy, with the goal of finding creative measures to increase the national homeownership rate. Clinton went on to declare June 5, 1995 as National Homeownership Day. Not to be outdone, President George W. Bush declared June 2002 National Homeownership Month. Later that year, addressing the White House Conference on Increasing Minority Homeownership at George Washington University, Bush said, “All of us here in America should believe, and I think we do, that we should be, as I mentioned, a nation of owners. Owning something is freedom, as far as I’m concerned. It’s part of a free society.” He could have lifted that directly from a Gene Percudani “Why Rent?” ad.

According to historian Thomas Sugrue, until the early twentieth century, holding a mortgage was a source of stigma: “You were a debtor, and chronic indebtedness was a problem to be avoided like too much drinking or gambling.” But in response to the Depression, federal housing programs — beginning with Herbert Hoover’s Federal Home Loan Bank in 1932 and continuing through Franklin Roosevelt’s Federal National Mortgage Association (Fannie Mae) in 1938, and beyond — established a pattern of easy credit to boost rates of home ownership. With these programs rose what Sugrue calls “an army of banking, real-estate and construction lobbyists,” determined to protect their industries’ gains.

By the latter half of the twentieth century, then, the idea of “homeownership” as a measure of American success and stability had become entrenched. Never mind that what most Americans owned were mortgages, made possible by federal programs. Still, Sugrue notes, tens of millions of American homeowners “had no reason to doubt that their home ownership was a result of their own virtue and hard work, their own grit and determination — not because they were the beneficiaries of one of the grandest government programs ever.”

Every American wants it; every American deserves it. Do we really know what every American wants? What every American deserves?

Every American wants it; every American deserves it. Do we really know what every American wants? What every American deserves?

Some green space? Some safety? Abundant — and drinkable — water? Easy access to the places we want, or need, to be?

And a gate around it all to keep out latecomers?

Thomas Sugrue has pointed to another disturbing statistic from recent years: In 2006, the last “boom year” for American real estate, more than half of the tainted subprime loans went to African Americans — who make up only 13 percent of the population.

6.

Drawing on the writings of Aldo Leopold and Wendell Berry, Eric Freyfogle tries to frame a new way of understanding property, one no longer rooted in notions of boundless resources and manifest destiny. “The core of their message,” he writes, “is simple and direct: the time has come for America to put the pioneer urge behind, to craft ways of living that allow life to flourish in every neighborhood, consistent with the health of the whole.” Maybe even renters could share in such a vision.

Another poet had a similar vision, back in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries in England, at the time of the Enclosure Act, with its passing of commonly held lands into the hands of private owners. In his poem “The Moors,” John Clare harkens back to his childhood days — before enclosure — in lines like these:

Unbounded freedom ruled the wandering scene

Nor fence of ownership crept in between

To hide the prospect of the following eye—

Its only bondage was the circling sky.

What do we want? What do we deserve? When we mindlessly absorb more land “to build a house / on to build a / house on to build a house on/ to build a house / on,” in the language of Williams’ broken record; when we repeatedly fail to make comfortable, and safe, housing available to poor and working Americans, despite our National Homeownership Strategies and Societies and Days and Months; when we continue to put our water supplies at risk in our endless search for cheap and readily available fuels — what memories of “unbounded freedom,” of the “circling sky,” are we suppressing?

Frost wondered as much, in “A Brook in the City,” which closes with these lines:

No one would know except for ancient maps

That such a brook ran water. But I wonder

If from its being kept forever under,

The thoughts may not have risen that so keep

This new-built city from both work and sleep.

Delaware Water Gap images credit: Jim Hauser