“There is no change of death in paradise.”

– Wallace Stevens

1.

Pitch dirt onto a parent’s dead body and in that second understand that bits of dirt just became as much part of the parent as any other bit you might hold onto: a snapshot, a clock with bent hands, shoes still bearing the imprint of feet, ties scented with stale aspiration. We mortals grasp. In my father’s last minute as a living, breathing, incorporated entity, he was on the phone with me – or rather a nurse I’ll call Bob held the phone up to my father’s ear.

Before my last conversation with my father last September, the first of many unilateral discussions ever since, I had fallen asleep next to my three-year-old, helping her go to sleep, a custom probably far too common in our house with its tilt toward entropy.

This house: it is situated in the kind of town for which Manhattanites leave the grid. Faces radiant, they come to trip over our uneven sidewalks, aquiver with the possibility of serendipity and rustication. Obedient to hebdomadal divisions, they rise for their upstate sabbath fully pagan, rousting in ancient corporeal nostalgia: antiques and wine, jam, farmers’ markets, holiday festivals, round bread, any ritual useful in making sense of time, not to mention the oddity of toting around a body bearing desire and all its malfunctions.

My father, a geophysicist, would have remarked less on the Manhattan tourists and more on the old granite of upstate New York, its igneous intrusive so different from the endless metamorphic slop and shift of soft Californian plates in which sections of oceanside cliff change overnight, where if a tsunami won’t get you, a shark will.

This same scientist once stood in his office, an old, almost condemned Art Deco building in an Oakland not yet refurbished by Jerry Brown’s idealism. Under and around him the great earthquake of 1989 terrorized the earth. In a building not up to code in its seismic retrofitting, there my father stood under an antique chandelier and not under a doorframe as all Californian schoolchildren learn early in primary school, nor under a desk or table, but keeping his balance on the rolling earth.

From timing the swings of that potentially lethal lamp, my father factored the P and S waves on the surface of the land and in this way estimated the geographic navel of the earthquake, its epicenter. Later he was pleased not so much to have survived without a scratch, given that the quake figured 6.9 on the Richter scale and caused scads of devastation, but rather more tickled that his knowledge of California fault lines and mathematics had positioned the epicenter accurately, some fifty-six miles away on the coast of Santa Cruz.

The night of his death, while half-sleeping in New York, the night that started a period of not just unilateral conversation but unknowable maps, I heard my husband say: I got a call. Your father’s dying. This time it’s real.

For years this father, half bon vivant and half scientist, had been creeping farther and farther out onto an isthmus of abstraction. I found it easiest to understand the clouds that increasingly populated his watery blue eyes and his similarly aqueous mind as some brilliant philtre the body seeped into one’s brain as a way to soften the fear of dying.

My father loved to put on a brave show. Despite his early years in Israel that had made him a chalutznik, yet another pioneer taught that men should sport only fur but no sensitivity, like all of us he had his favorite talismans against fear and the frequency of their apparition could show even a casual observer how afraid he really was. His military posture, for one, with its rigid grace, which made his bearded self look at, say, a party – this was a man who loved parties – like a blue-eyed Lincoln reconfigured as your average broad-shouldered lieutenant. He would sit smiling and upright as if to say: I am here, I claim this spot on the mobile earth, nothing threatens me, I am ready for pleasure.

Another talisman against fear would be one of his favorite morning songs, a kabbalistic melody whose words, translated from Hebrew, told him that all the world is a narrow bridge, and the most important thing is not to fear (the passage from life to death). In his long, stretched-out dying, he showed a survivor’s tenacity, his final talisman: if theoretically he wanted to die, in reality he found it hard to leave the party.

2.

We the living become quick adepts in our trafficking in the jargon of meds which, in our modern-day business of dying, act as a professional undertaker, fake in their helpfulness, the words that slither and whisper and prompt us alongside our slow processionals toward a funeral.

Or you could say we become a kind of snake swallowing the elephant of death, à la the illustration in the early pages of The Little Prince which shows the elephant bulging inside the boa constrictor.

Or you could say we become a kind of snake swallowing the elephant of death, à la the illustration in the early pages of The Little Prince which shows the elephant bulging inside the boa constrictor.

Therefore, to use the jargon our family so obediently swallowed: for months prior to the flash and siren of the last ambulance taking him to the last hospital, my father could be found in a “skilled nursing facility”, an infelicitous phrase which always made me wonder, what, as opposed to that other facility known for its staff so judiciously unskilled?

In his non-home, attended to by those with skills, he had been lying in bed or in a wheelchair, playing pioneer tunes on his harmonica in desultory fashion near the nurses’ station, positioned on an island which was a decommissioned naval base out in northern California. Could it have been more perfect that the name of his home, dedicated to liminal states, was Water’s Edge?

What I tried to understand that mapless last night of his life was that this time his dying was real. From our entropic New York aerie, this was the totality of what I could divine.

I sat in our tiny dining room next to my husband who was dialing the hospital and using his best Brooklyn-bred diplomacy to get through the telephone lines into the exact right artery that would lead into the ER and whatever last bit of listening might be left in my father’s ear.

I should say that I sat like a penitent schoolgirl, fists clenched between tight knees, waiting in a room that had just lost its circulation. I chilled, for once the phrase right, since the temperature of the world had just dropped. While my mate tried getting through, it seemed everyone else in my family also tried the lines, this being a family not known for its lack of words. Of course at this second the lines would be getting clogged, heart to head, family flocking to its cerebral patriarch, and in seconds I would lose the chance to – to do what? Use words to sustain a last moment? Did the urgency of needing to talk to him have to do with affirming our connection? To say life and all its recent indignities had mattered? To show that despite being geographically challenged I would care and then care always, memory conjugated out over the rest of my lifetime? I cared, I care, I will care, those who don’t know you will care, you have a legacy.

Before those crucial seven ounces of consciousness left his body, I had to tell him he mattered, that all of the suffering and aspiration of his life had been worthwhile, that we mattered, that he would continue to matter within the context of the living.

3.

Since the dawn of the answering machine, I have been a phone-phobe, voice seeming such a poor substitute for presence. This unfortunate sensibility makes me lack the grace of friends who sound ready and delighted to answer a ring, those with the talent of making time expand accordionlike in their affinity with Graham Bell’s invention. Instead, and this serves as no apologia, I seem always to hang up first, cavemanlike, unrefined and coarse: there should be a twelve-step program for those like me. Hi, I’m Edie and I do bad phone. While email redeemed most of my social life, which it did, my aversion to the phone stood as one of many traits which my father, with his take-all-comers attitude but his unfamiliarity with computerized letters, accepted as a quirk.

Simply, therefore what I was awaiting in that pendulous minute before my minute to talk with my father arrived was this: make of the phone a friend. It was all I had.

My husband handed me the receiver and Bob the nurse came on to say: You want to say your goodbyes.

Right, I thought in that nanosecond, brilliant, that’s the name for it, I’m going to say my goodbyes.

The plural fit for a man of my father’s complexity, suspended in a metaphysical state of so many parts, within a state of so many pluralities.

And until that moment I had not realized that every person has stored within some finite amount of goodbyes for each person who matters and that right now, despite all brink moments and prior goodbyes, I was about to use up the last goodbye, tagged for him alone. This time the goodbye reverted to a greater status. I was about to spend my last goodbye as if some Maximum Leader had just declared the currency of goodbye not debased by all its manifold apparitions. This time the currency would count.

4.

For five years, all my father’s near-deaths had summoned me from New York back to what will forever feel like home: California. Each death seemed realer than the one that came before. Each time my father’s Egyptian lady doctor said to me if it were my dad I’d come now. Westward I flew, often with a baby on my lap, and the babies grew. The youngest especially became a fan of firetrucks, given the coincidence of their hectic arrival, coming to oxygenate her grandfather every second day after we arrived for a visit to California.

There he would be, in his medically outfitted room off the kitchen on the lower level of my parents’ house, his heart exalted by the nearness of family but his lungs drowning in the fluid that kept wanting to fill that aqueous spirit, and once again we would be summoning empirical data and conventional logic in order to persuade the scientist, the traveler who now wanted to stay home, that this was something of an emergency. There I would be, fingers robotic in dialing 911 for the firemen to come again – I got to know them — up the fifty-one stairs to the house in order to put yet another oxygen mask on him and spirit him away and me into the plethora of questions that came in his wake, all from the young truck-lover (who now every night, her choice, her subliminal Yahrzeit, sleeps in a plastic replica of all those firetrucks):

Where do the firemen take him? Why does Saba wear that mask? Will they fix Saba so he can walk again?

And my own questions, all mainly circulating around this question: did he not once get me to promise that his life’s coda would have the dignity of freedom he had found in his adopted state?

But who was not to say that in his travels, bedbound, he was not fulfilling the imaginative promise of California?

5.

Consider the name. Unlike other states drawn from Spanish – Colorado (“red”), Florida (“flowered”), Nevada (“snowy”) – the name California itself is a made-up place, drawn from a fantasy land mentioned in Don Quixote. Which suggests how readily you, too, can project on a land made up of such shifting plates. It is a shock to encounter, say, a tenth-generation Californian – though they do exist, great-grandchildren of dusty legacy and agricultural ingenuity, usually the great-grandsons of early ranchers with some Mexican or Spanish romance thrown in.

Consider the name. Unlike other states drawn from Spanish – Colorado (“red”), Florida (“flowered”), Nevada (“snowy”) – the name California itself is a made-up place, drawn from a fantasy land mentioned in Don Quixote. Which suggests how readily you, too, can project on a land made up of such shifting plates. It is a shock to encounter, say, a tenth-generation Californian – though they do exist, great-grandchildren of dusty legacy and agricultural ingenuity, usually the great-grandsons of early ranchers with some Mexican or Spanish romance thrown in.

Consider that whenever America encountered problems with coexistence, which sounds better in Spanish, convivencia, it expanded its territories westward, so that a slow seep of individualism spread from the tight eastern harbors out toward the hyper-individualism of California, which may go a long way toward explaining why people from the middle states tend to be so other-directed and polite, a legacy of making do enough to declare, as in the license plates of Oklahoma, hey, this state is okay.

While people in California must perform elaborate yogic or Buddhist tricks to come out feeling their state is okay. They come to California to go beyond the quais, to find their big dreams, seeing it as Don Quixote might have: the state will be a kindly queen, allowing them to realize in large acres and billboards their fantasies.

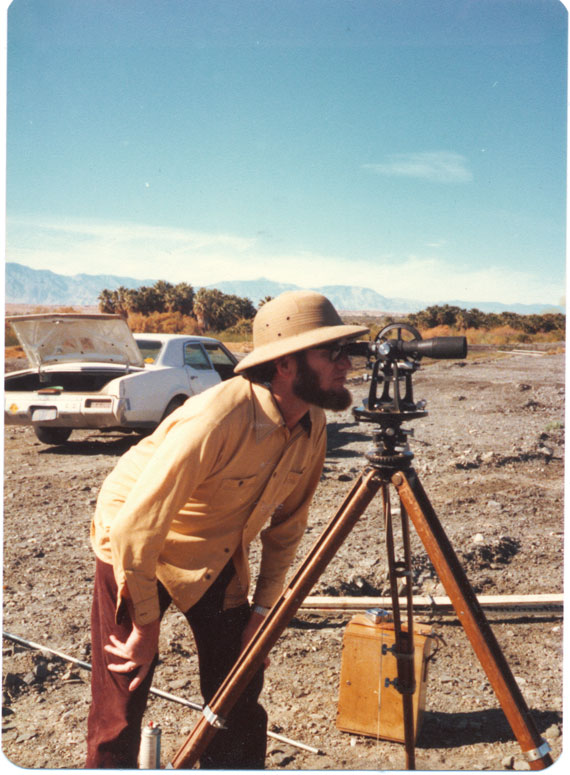

This was how my father, a resourceful, adaptable person, well-suited in psyche and profession to the state, used it. An ambitious restless geophysicist, he was dedicated to, as one of his company’s business cards had it, the evaluation and exploration of natural resources.

Part of the liberty of the state, of course, has to do with the weather: it rarely constrains you, and when it does, the constraint has the dimensions of a Greek tragedy, as only the biggest ecological disasters take foot here: earthquakes, tsunamis, mudslides, fires, geological capstones fitting the dimensions of the state, the heroic flaws and grand destinies of those drawn to it. If every state has a psychological age appropriate to it, California is forever an adolescent, dreaming in bright colors and assuming suicidal proportions at its misfortunes.

Which may be one of the reasons, right before we moved into its take-all-comers embrace, the state assumed leadership in that youngest of decades, the sixties: the civil rights movement, the free speech movement, the rollicking music and the rocking hills of Haight-Ashbury all fit the national demographic bulge of youth. Accordingly, the majority of my friends’ parents came from the following range, one drawn from the disappointed dreams of youth: drifters, horse-race gamblers, Vietnam vets, café chess players, social agitators, drug users, therapists, famous musicians, polyamorists or ex-psych ward types.

Many were divorced, or separated, or lived in alternative arrangements. By contrast my family seemed solid and well-endowed, conventional, with two working parents, their indiscretions unknowable. California and the times may not have made much of a dent in my parents’ Old World creamed herring and Mediterranean tomato-cucumber-lemon-onion diet, but it did allow them to wear peasant shirts from my father’s many travels at all the many parties they hosted, parties in which my mother, an engineer at the public transit system, would invariably at some point don her green jeweled bellydance outfit to shimmy before the guests, ululating as she had taught many of them to do, often accompanied by the happy jiggling students she also taught in a swirl of cloths on Sunday mornings, all before she invited my father up to do a sort of loose-hipped sheikh host imitation with her before all of them: California at its multiethnic apotheosis.

Come to the party and we’ll dance for you!

The one common social denominator in any setting was this: the body, its hopes, its staving off of decay.

6.

My response to this awareness of social disparity – all that we seemed to have in relation to all others seemed to lack – was to try to bring people in to what seemed the potluck bounty of our house, and even without my intervention, an uncountable many came and lived with us. A lost mother of a friend with her daughter; the daughter of a pot-smoking vet who later became something of a celebrity murderer; a German exchange student; a therapist; a secretary; a massage therapist; a lost philosopher; a friend with stepmother troubles; a friend with stepfather troubles. The list goes on. We had a succession of housekeepers who lived in the basement apartment, and one had an ex-boyfriend who came by, parking his red-painted former milk truck on our cul-de-sac for a week. I would bring him treats until I finally asked my parents if he too could not live in the house, one that had been bought for $25,000 back when that area of South Berkeley, not far from the invisible but real border with Oakland, was considered too close to racial troubles. In our basement kitchen, this latest of our inhabitants penned for his dented guitar a song that ricochets around my head sometimes, a Californian anthem with one of those strident melodies of childhood:

I’m a drifter and I drift this world around

And I know who I want to be and just where I’ve been

To be free to flow with the wind (2x)

And despite or because of all its disappointed dreaming drifters, the town seemed to function, believing itself a microcosm of the world, the best of the best to be found there, believing itself potent on the world stage. Alice Waters was starting Chez Panisse, the gourmet ghetto mentality of the town was radiating out, the town was claiming its position as the only American city to have its own foreign policy and my father’s grandiosity linked with the town’s.

Just as, after an early rise and fall in sheep husbandry, my father had gotten involved with geothermal energy, because geophysics seemed a concrete, practical way to help Israel and also, somehow, to save the world, just as every family trip we ever took had to do, inevitably, less with pleasure and more with a visit to sulfurous, spitting sections of the earth where you would be dwarfed by the grandeur of nature and its machinations, even after the fog of his dementia started to cloud in, my father never proved lazy.

As he started his long slow dying, I would, as ever, try to make of the phone a friend and call him. If I asked how he was doing, he might say: well, some medieval colleagues and I were trying to figure out all the names of god and the colleagues were really quite congenial. Or: someone handed me a capsule containing a worm that could destroy humanity and I was just figuring out the best way to save everyone.

He had, like the small liberal town he had chosen, long had a utopian mission to save the world. He had started an Israeli cultural circle and would invite prominent Bedouins, Palestinians, and Arabs to come speak to that volatile group of talkers. He supported causes, soup kitchens, candidates. The Department of Energy named him, with great ceremony and a placard, an energy pioneer. He did what he could in his way, writing a poem that appeared in a millennial anthology Prayers for a Thousand Years that had a last line that went something like this

He had, like the small liberal town he had chosen, long had a utopian mission to save the world. He had started an Israeli cultural circle and would invite prominent Bedouins, Palestinians, and Arabs to come speak to that volatile group of talkers. He supported causes, soup kitchens, candidates. The Department of Energy named him, with great ceremony and a placard, an energy pioneer. He did what he could in his way, writing a poem that appeared in a millennial anthology Prayers for a Thousand Years that had a last line that went something like this

May I in my small way do the best I can, knowing that for my time I did the best I could for others

And for all his love of trafficking with high and mighty causes, people, places, he remained a socialist, a person who wore the same holey plaid shirts, who would say, if a vase broke: it’s just a thing. He never went out without a roll of quarters in one of his threadbare pockets, ready to dispense change to people in need. He was unafraid of homeless people found sleeping in his car and would give them a ride wherever they needed. When at age fourteen I was caught stealing sunglasses for my brother’s birthday, from a drugstore on Telegraph Avenue, the open-air post-hippie emporium street that hosted so many lost denizens, under the influence of all those friends the product of those broken post-sixties Californian homes, my father did not scold me. Instead he merely shook his head, hours after my release from a scary graffiti’d cell, and said: Look, Edie, it’s never the thing that counts when you give a gift, it is the thought. Thought is everything.

In later life, accordingly, he also inhabited his body as if it were an uneasy, stolen perch, an afterthought, a car in which his homeless self happened to find itself. Once, on a business trip while I was living on the Upper West Side, he visited me and said goodbye to me on Broadway. I watched him walk away, his back disappearing into the sidewalk masses. A father barely skimming the earth, he carried not even a briefcase, a stick-skinny man whose movement radiated out from a loose central axis, his wrists flopping out a bit as if the wind could spirit him and his untailored suit away.

7.

Sometimes, during my father’s long dying, our upstate-New York family flew west to spend some summer month in one housesitting situation or another, caring for this canary or that dog, my daughters delighted to be in the ease of extended family and the weather that surrounded them. Their sociable grandfather, who had always had a bipolar way of saying goodbye – either expert in the gooey and endless Jewish art of goodbye, or Israeli in the way he could say, for example, to someone he was chauffeuring I love you, now get out! – would be equally delighted by the multiplication of family.

His party never ended, the goodbyes never stopped, and meanwhile the meds worked their damage, fighting a war in his liver, the meds that said to his corporeal being, essentially, the opposite of I love you, now get out!

I destroy you; now you must stay in life!

8.

A few months after my father’s death, the attending doctor described Bob, the last person in that last room, as a kind and dedicated representative of the art of nursing, a practice for which I only gain respect each passing year of my own life as a two-time mother and mortal.

There Bob was, on the phone in that expanse of time, his voice so dry and tight it almost sounded sarcastic, conveying over the unclotted line the atmosphere of the emergency room, thick with death, telling me: You want to say your goodbyes.

Yes? I said.

You can talk, he can hear you, he said.

He could hear but could he listen? Back to the character of this father of mine. In the same way that I was living in exile, out in New York, forever hankering for the calm skies of my northern Californian childhood, the freedom of being able to go outdoors with your children any time you darn well chose, my father had lived his whole life in exile. We grew up in a little Israel of the imagination, set, provisionally, in the liberal airs of Berkeley. My father’s Israel had begun in 1933, where he had moved when he was three. Prior to that, his family had lived in the small Polish town of Przmsl where his father, Joshua, had been a woodsman and a community leader. When anti-Semitism roved their town like some fanged beast, Joshua scented survival and took his family to Haifa. Soon after, all the family — the uncles and grandfathers and cousins who remained in Poland — were killed.

Survival instinct, therefore, lived deep in the nature or nurture of the family.

Someone who married into the Meidavs traced our geneology back point by diasporic point through the Maharal of Prague, the Baal Shem Tov and Rashi, through Lucca, Italy, through the house of David and all the way back to some humble Palestinian second-century BC sandalmaker named Yohanan, and something about this millennial-long connection to the land paradoxically provided succor to my increasingly leftist father who loved the ideation of the Palestinian thinker Sari Nusseibeh. To his death, this American exile remained an exponent of the two-state solution, clearly a “yored”, a person who had “come down from” Israel, a distant survivor of an era and not, as our Israeli cousins liked to point out, a person on the ground, like his more rightist brother who had remained in Haifa.

Part of my father’s lofty idealism – so well suited to both California and his Israel, the Israel of the 1950s, before a moral conscience started riddling certain sectors — meant that a favorite book among the many antique books in his collections was a set of lithographs done by David Roberts, Travels to the Holy Land, in which the Englishman had penned lovely romanticizing images of Bedouins hunkered down by a well, little aquarelle-like images of the land and its peoples coexisting, and for copies of books such as these, preserving the memory of a time before strife, my father would travel to book fairs seeking out unfoxed copies of the early Holy Land.

In this way and in so many others, my father was ideally suited to California. Because California seems to listen but insists on rose-colored landscapes. It has the compelling charisma of a narcissist, one which lures emigrants out to fulfill internal, narcissistic dictates. In its royal beneficence it makes lifestyle urges, ethical or sybaritic, holy, the body its temple.

9.

Stay simple, a handwritten imperative on the cover of a notebook of one of our Berkeley house’s many inmates dictated. Stay simple, an idea perplexing my child’s mind. Was it better to stay simple so one could feel the world and all its categories better, anew, as if one were truly an innocent? Or was it better to gain in the intricacies of the world, cultural or natural, so that one could better understand its phenomena? Is it better to know the name of a leaf or does knowing the name mask appreciation of the leaf?

If you could, hypothetically, wash yourself clean of culture, would you then live the life of the body more purely? Our California had all the romantic-savage idealism of Truffaut’s Wild Child, in which the wolf-boy loses the inner truth of his body once he is civilized, yet our California also had the gourmet jadedness of your average American international food court: sample the best of everywhere else, become a multiplied citizen, and why ever leave? Motion could become stasis in the perfect microcosm of Berkeley.

10.

We came to the zion of California, and specifically Berkeley, after my family had already tried out Saint Louis, Haifa, Toronto, Westbury. We came the year the sixties truly ended, that is, in 1974, when the whole city was entering what I would later realize was one prolonged hangover, the buzzkill that included Reagan, the Charles Manson years, the various propositions announcing that people did not want to pay taxes to support anyone other than themselves. Vietnam veterans smoked their only pleasant artifacts of the war, their tiny pinched hoardables, sitting on the curbs along Telegraph Avenue, the main drag toward the university, steeping the whole area in sickly sweet fumes. Open-air sellers sold hippie jewelry – and what did ever happen to macramé, which seemed such an important art to my young self, as important as basket-weaving or the making of incense-holders? – underneath a mural depicting the people’s struggle to save People’s Park from the pigs, the police. There was a sense of revolution mutely dimmed. Now the bourgeoisie got to eat their massive alfalfa-sprout salads while kids growing up during that time in that place got to see what happened if you went the way of drugs, a massive cautionary display on every corner.

So in the end the body became the path of improvement

California’s adolescent desire to make a better world, once nipped, became the realpolitik of someone entering their late twenties and early thirties, the more mature evaluation made by someone who realizes their own risks and mortality and who then makes adjustments.

In the buzzkill years, seeded by a genealogy beginning with the Jack LaLannes and continued by the Jane Fondas, what the state’s citizens were left with was the body. In the state I grew up in, the body was everything. You could retreat into the body and its nurturance and rejuvenation, its vitamin protocol or cryogenic suspension. Retreat into a fanfold of body therapies because the body would not betray, or if it did, it was your fault. You could control your health, as well as your fate, and any illness was a sign of poor internal combustion. Every adult I knew was dedicated toward some form of self-development, and these forms usually radiated from and toward the body.

From northern California all these body therapies – what we could see from another vantage as focused outcomes of the gold rush — were introduced, refined, reified, consolidated. Trager points, polarity, dance continuum, Rolfing, tai chi. Because, finally, when you had renounced your birthright, when politics had betrayed you, when you could not believe in your dreams, in community or connection or culture, you would always have the body, its urges, and the sophrosyne of the state writ upon it. You could endlessly self-improve, climb fire trails, eat more phytonutrients, meditate for hours a day and thus insure your own longevity or at least your survival when the great cataclysms would come, and bet your earthquake insurance come they would.

On the east coast and perhaps everywhere else, when people find a body therapy they like, they cling to it as if it is a splintered board after a shipwreck, singular and intense in their devotion to it, truly zealous acolytes in crowded corridors in Manhattan or in meetings in little hard-to-find restaurants. But on the west coast, people slip in and out of the ever-present therapies – because to survive in a place that doesn’t squeeze your contours with a social contract as, say, with New England’s lawns and flags, you need to have some kind of pressure around your corporeal self – with an ease and blending akin to all the state’s experiments with pineapple and pimiento: California Pizza Kitchen indeed.

11.

My parents were not wholly immune to these new-fangled body therapies but also, interestingly, managed to remain in a prior century. My mother used olive oil on her face; my father used hair grease, part of a storm-cloud gathering of intention prior to any important business meeting. Of course he had other icons, all bespeaking the dream of ultimate mobility: the cologne of departure, the briefcase, the traveler’s Dopp kit with its tweezers, band-aids, scissors, shoe polish, an open briefcase. Most of my father’s life was spent in movement. When I was young, he would travel for months at a time for the United Nations to develop sustainable energy projects in Ethiopia, Honduras, Kenya, the Philippines and who knows where else.

My favorite memory of him from my kindergarten years is of a card he sent to me in his careful, floral immigrant cursive, a bird’s African feathers tufted on the front. In his absence, like our last phone call, the token became everything, a talisman of presence.

After his brief stint for the U.N., where he couldn’t stand being a company man, out in California, the land of possibility and future attainment, he started two companies. Over his career, he traveled the world and it was only after his death, as I took the plane westward that chilly middle of the night, that I realized that on planes, trains, boats, in any movement whatsoever, I had always been closest to him.

A few months after his death, I went on an already planned research trip to Nicaragua and realized, as the plane began its touch-down in Managua, the local women around me busily applying eye-makeup against the backdrop of volcanos, how so many moments of his life were spent in true California sybaritic fashion, enjoying and appreciating the artistry of the people around him.

Of, say, the chef at the Hotel Cesar in Managua.

I knew how much he loved this hotel because he had taken me to it once, on a business trip where I would serve, nominally, as his interpreter. For him, as with any Californian doing tai chi in the sun, any pleasure could be justified if it could somehow be categorized as being in the service of utopian work. Since he was forever a man confident about his children’s capacities and blithe about risk, being the kind of person who had fallen many times in his life – once down an elevator shaft in Haifa, once into a geothermal hot spring in Greece — he decided to send me, on this first trip to Nicaragua, packing with a team of boys on laden burros up the volcano of Momotombo so that, using machetes ahead of the burros as we rode, we could place antiquated seismic monitors in strategic locales.

He wanted me to know the liberals’ favorite fantasy, the pleasure of being one with the people; he thought I would want this experience and in this he was not wholly wrong. While he certainly liked knowing fancy people, he was also wholly unpretentious in how he tried to connect with anyone he met, whether parking attendant or fellow passenger, and was always filled with stories of strangers he had met on a trip, humble or grand, this woman whose charity in Nicaragua he had decided to support or some Oakland Baptist evangelist whose family needed succor.

In his desire to give me this common touch, that first trip to Nicaragua, of course he could not have predicted that perhaps it formed part of the strategy of this team of Nicaraguan brothers to lose me and the youngest brother in the endless jungle so that the youngest could entertain half a hope of losing his virginity, and that this meant that the brother and I ended up truly lost, with no water or food, clinging to trees above the nighttime cobras. Nor could my father have predicted that in the morning we would magically manage to pull the reluctant burros on circular paths toward, finally, an exit from those miles of wilderness.

After the slow return back to the safety of his Hotel Cesar, his home, after this life-or-death jungle experience, I was perplexed by the way my father sighed, relieved: I am just glad I did not know it was happening. I would have sent helicopters to try to rescue you.

Perhaps this meant that he would rather remain in hopeful ignorance than have to admit to friction. This possibly Israeli trait was another that suited him well to California, where people prefer to pursue the specificities of lifestyle, each one facing the ocean, rather than being aware of the particularities of all who rub shoulders next to them.

During that first visit to Nicaragua, after the life-or-death experience in the jungle, he and I stayed a few more days at Hotel Cesar where he chatted often with the chef, a bit like Hemingway in Cuba if without the drink. He was apparently happy to sit poolside, speaking an intelligible if slow Spanish to one after another person in endlessly futile business meetings.

His Nicaraguan ventures, motivated by a typically idealistic desire to provide a sustainable clean energy source to poor people, never quite got off the ground. Part of this failure, as one associate later told me, had to do with his refusal to adhere to important local customs, bribery paramount among them. And clinging to some self-spun philosophy, his fortunes went down, as they often did, like those of your average 1849 gold miner.

12.

When I came for the second time to Nicaragua, I was glad to be in a space not demarcated by him, a tatty little inn and not his Hotel Cesar, though I, nonetheless, like him, relied hugely on the kindness of strangers. On this trip, soon after his death, I felt especially close to him, a father who easily made of random new acquaintances a mobile family, much like the energies of his chosen profession and our California. What he had bequeathed me: to be in exile, making only of the body and one’s immediate acquaintances a home.

His most religious custom was to check into a hotel in some foreign city and then to call home, call my mother, call any one of us to tell us he had gotten in and what his latest geographical coordinates were: the purpose had arrived at its goal, and in this, my parents accorded each other great latitude. In movement – the dream shared by Zion and California – one could find meaning, purpose, belonging.

Say your goodbyes then, said Bob the unflappable nurse.

In other words, make a cord to a man of so many moveable parts.

In that one last second I had to talk to him – fittingly exiled — the trumpet-blast of a lifetime together came out of me:

Dad, I said, never having really known what name fit a man of so many origins, you are responsible for so much of anything that is good in me and your children and grandchildren love you and we’ll do what we can to honor your memory and legacy and all the good you’ve sown and you’ve been holding on so long and now it might be your time to let go and do you remember that song you loved about all the world being a narrow bridge, the important thing being not to fear and –

I got to hang up now, said Bob the knowledgeable, sixty seconds into my swan song.

Thirty seconds later, according to later reportage, my father, who allegedly smiled and nodded lightly as I spoke, was dead.

No one gives you a user’s manual to how such moments proceed. Somewhere inside I had signed a contract that I would be by my father’s side when he died, a kind of fellow traveler, as if my childhood in Berkeley – that made-up Californian confection, a pastiche of a bardo, made up of everyone else’s in-between spaces, a kind of tunnel — meant I had to be with him in this final threshold zone.

That we had that last moment could have relieved me, just as my father was relieved not to have sent helicopters to rescue me from near-death in that Nicaraguan jungle. To be close but not to have to feel the pain of potential separation.

I could have said: jeez, at least I got to talk to my dad in his last second. He heard me, he smiled.

Instead, when a minute later the doctor called us in New York to tell us what we already knew, I felt I had betrayed my father’s legacy. I had not been by his side. I had taken his California Zion lesson too deeply. I was a person too much in movement, too much a traveler, exiled, too far away, following dreams of my own.

And still that doctor’s call released me from a deep freeze. I ran through our house as if on amphetamines, middle of the night on tiptoes, unable not to rush, as if it would change anything if I were speedy in booking a ticket from Albany, the nearest airport, so I could fly toward California. We the living scurry while our dead have all the time in the world. History sleeps and we hurry toward our ends. Plus I did not want to wake my kids to say I was going. Their relative innocence, lips fluttering over crucial dream-words, seemed crucial, almost more important than whatever had just happened. This was how my psyche compartmentalized its loss, organizing its metaphysical sock drawer. If you don’t orphan the details, you won’t have to see your own orphaning.

In a cold car in a parking lot in the middle of the night at that Albany airport, I pretended to sleep before my flight, enjoying the physical discomfort. No bed of nails could have been spiky enough. Already in movement I was closer to him but I still needed a physical correlate to the metaphysical dislodging death performs, some way to show my father I understood what his body might have known, despite its hyper-sedation, in all its recent injustices.

13.

When I got to California, it was somehow fitting that the religious mandates around his burial kept me from seeing his body on that first day. My siblings and I sat outside the back door of the locked, squat suburban building within which a guard sat praying over his body. We looked past native wildflowers into a valley half river-rift and half tectonic shift, with a large silver aqueduct lacking, in typical drought fashion, its water that could spill down into the canyon, exactly the kind of landscape my father would have appreciated: the grandeur of nature with a small token of failed human intervention, your archetypal Californian scene.

The next day, I sat in a room in that squat building alone with his body, so oddly still and yet alive, his huge bony head looking peaceful, the love that he radiated out to so many chillingly present in the room.

My youngest daughter, the firetruck lover, the three-year-old who has something of my father’s brow, had told me that morning she had glimpsed Saba walking in the house again and that, scared, she had hidden from him. The night of his death, before we knew he was dying, before I had put her to sleep in that upstate house with its tilt toward entropic custom, she had been trying to tell me, with strange insistence, that sometimes people go to hospitals and then they die.

I had chalked this up to, merely, her metabolism of some talk she’d heard about a month prior.

Earlier that same day of his death, I had been teaching two classes. In the first, after hearing a particular student story, I’d had an uncanny urge to tell my students the story of the death of one of my father’s closest relatives, but had suppressed the urge, as it had no obvious correlation with any pedagogical point. In the next class, I had been struck with the urge to laugh uncontrollably, much as had happened at the exact moment of death of a best friend of mine, many cities away from me, years ago and soon after the shoplifting incident, while I had been sitting in a class in a troubled Jerusalem.

Perhaps these occurrences – my daughter’s insistence on the suddenness of death, the odd telegraphs I wanted to convey to my students but did not — were nothing or perhaps they are as strong as the telephone cord. What ties the living to the dead, after a while, has mostly to do with the cord of belief, while the soul of writing will always be elegy: one uses words to create a trail back to some missing source, the platonic home you hope for but can never quite reach. Like the hundreds of unfinished highways you find in California, founded in big dreams and crashing in reality, all the roads that begin, continue, and never reach its end, this bit of writing is, perhaps necessarily, unilateral, incapable of neat conclusion.

14.

I write this now from the lobby of a Cuban hotel under a statue of the one omnipresent heroic American you find here, Lincoln, the emaciated liberator, almost as ubiquitous as Che or Fidel, Bolivar, Allende, Maceo, Martí. My family, daughters and all, have been living in this country in an apartment owned by a slumlord on a street spilling over occasionally with rivers of sewage. For days at a time, we will have no water; on other days, the gas or electricity goes. To live here you live inside a national body, the scent of cologne and urinals and sugar everywhere, sugar being a useful substance for keeping a population somewhat peppy. It seems that only on certain government-decreed days, the chickens lay and you find hundreds of people gleeful as they carry gray open trays of eggs home for safekeeping. At scheduled hours, bread appears in the bakeries and every passerby hoists a triumphant loaf of fifty grams, no more and no less. Every restaurant’s menu lists tantalizing items that will never be obtained by anyone.

As legend would have it, the people, however, are mostly a constant party.

In this travel, its deprivations and pleasures, I seem still to be performing some kind of wake for my father, a man who always managed, in his way, to find gold in dirt.

This hotel from where I write is a sybarite’s enclave in an uneasy socialist utopia. As if I have just crawled out of some gasless, waterless outback, I deeply appreciate its café con leche. The months here have made it easy to recognize travelers from Berkeley, flocked here in disproportionate number: they talk out of the corners of their mouths as if their next restless thought tugs for flight. If they are older, they are fit and wear practical many-pocketed vests and floppy hats, their gestures loose and expressive. If younger, they are tattooed, hefty in calf muscle and committed to years of travel, either as foreign guides in Latin America or still fighting the good fight for Che’s idea of the new man motivated by moral profit and not financial gain.

On this early Sunday morning in the spring, over the loudspeaker comes, on endlessly hopeful loop, a Muzak version, replete with Andean pipes and a rumba swing, of the one American song ubiquitous in Cuba, The Eagles’ “Hotel California”.

There she stood in the doorway

I heard the mission bells ring

I was thinking to myself

This could be heaven or this could be hell

In a purgatory of exile, movement, and endless hope, having carried no more than the government-mandated forty-five pounds of luggage into this country, light-handed and skimming the earth, I recognize: right now I am probably as close as I could possibly be to my father’s California, that rosy future and its impossible state, the one I’m pointed toward, the one that can never be.

Havana

March, 2011

All photos courtesy the author