1. Into the Tillmanverse

You never quite realize what Lynne Tillman’s done until it’s too late. She takes formal adventures in flavors of novels that had never before welcomed them. She carefully embeds details deep in her texts that others would dutifully (and dully) trot out up front. She crafts what feels like one distinctive, coherent fictional reality without explicitly connecting any of her long-form stories to one another. Published over two decades, her five novels so far build and explore what I call the “Tillmanverse” through the eyes and ears of worldly, culturally keen women (and one man), shapen or misshapen by their undeniable compulsions, obscure fixations, and grimly complex senses of humor.

The Tillmanverse now has one more extension in the form of Someday This Will Be Funny, a collection of short stories newly published by Red Lemonade. Their women (and occasional men) write copious communiqués, trust and distrust their memories, trust and distrust their imaginations, don’t quite reconnect with the cast of their past, see themselves in their relationships, move ahead at the behest of odd desires, and stake out patches of the cityscape all their own. What’s more, they do it in text that knows just what to tell and what to leave completely untold. Tillman tends to lay out her novels and stories in pieces, but with piece-curation skills like hers, who needs wholes?

The Tillmanverse now has one more extension in the form of Someday This Will Be Funny, a collection of short stories newly published by Red Lemonade. Their women (and occasional men) write copious communiqués, trust and distrust their memories, trust and distrust their imaginations, don’t quite reconnect with the cast of their past, see themselves in their relationships, move ahead at the behest of odd desires, and stake out patches of the cityscape all their own. What’s more, they do it in text that knows just what to tell and what to leave completely untold. Tillman tends to lay out her novels and stories in pieces, but with piece-curation skills like hers, who needs wholes?

Indeed, the latest book’s 22 tales showcase Tillman’s abilities in microcosm; what you find in them, you find in even greater depth and quantity in her novels. What better time, then, to take a look back at all her full-length novels to date? The more detailed your map of the Tillmanverse, the richer you’ll find your own wanderings through it.

2. Would you really call it agency?

Haunted Houses, Tillman’s debut novel, braids the stories of three women growing up in and around New York. The epigraph “We are all haunted houses” seems to bode ill, as if predicting for the protagonists 208 pages of playing receptacle for assorted traumas. While none of the trio endure quite so rough a time as that, they nonetheless live apparently shapeless lives pocked by impulse, inertia, and confused frustration. They display flashes of agency, whether about the places they live, the books they read, or the fellows they let in, but the book’s overall form never stops asking whether agency is really what you’d call it.

Haunted Houses, Tillman’s debut novel, braids the stories of three women growing up in and around New York. The epigraph “We are all haunted houses” seems to bode ill, as if predicting for the protagonists 208 pages of playing receptacle for assorted traumas. While none of the trio endure quite so rough a time as that, they nonetheless live apparently shapeless lives pocked by impulse, inertia, and confused frustration. They display flashes of agency, whether about the places they live, the books they read, or the fellows they let in, but the book’s overall form never stops asking whether agency is really what you’d call it.

Jane, constantly struggling with her weight, desperate to shed her virginity, and genuinely close only to her hokey, obese uncle Larry, ultimately loses that virginity to a dopey co-worker at Macy’s. The bookish Emily — “Why can’t you be more normal?” laments her mother — grows into a sloppy, lackadaisical culture vulture who attaches herself to English rockers and married Austrians. Grace, spooked in childhood by periodically tussles with her erratic mother and the sight of a blank-eyed farm boy tossing a bag of kittens off a bridge, drifts to Providence and becomes the spitefully reluctant muse of her gay, Oscar Wilde- and Marilyn Monroe-worshipping best friend Mark who stages plays at bars.

Tillman sketches the three childhoods in gritty enough detail to let you assume that, having established the wrongs foisted upon these ladies in youth — isolation, imagined frights never corrected, groundless disapproval, dead friends, freaky dads — she’ll proceed to deterministically follow the reverberations into three disappointing adulthoods. Yet she plays it just craftily enough to throw that interpretation into question while also avoiding the obvious move of getting these three together. From start to finish, Jane, Emily, and Grace remain united mainly by the late-mid-20th century in which they come of age and the geographical territory they do it in. Even when one breaks away, as when Emily takes a proofreading job in in Amsterdam, none shake their vague existential claustrophobia.

3. What we call personality

The travel bug bites Motion Sickness’ unnamed American heroine harder, so much harder that she never stops traveling — indeed, barely pauses in any one place — rendering normal whatever “motion sickness” she suffers. This twitchy peripateticism offers Tillman the chance to structure the novel both in fragments and geographically: you read a shard of narrative in Paris, then one in Istanbul, then one in Agia Galini, then one in Amsterdam, then another in Istanbul, and so on. The protagonist’s financial support? A bit of savings and a small loan from Mom — no wandering aristocrat, she. Her cultural armory? Copies of The Interpretation of Dreams, The Quiet American, and My Gun is Quick, and a love of Chantal Akerman and Luis Buñuel.

The travel bug bites Motion Sickness’ unnamed American heroine harder, so much harder that she never stops traveling — indeed, barely pauses in any one place — rendering normal whatever “motion sickness” she suffers. This twitchy peripateticism offers Tillman the chance to structure the novel both in fragments and geographically: you read a shard of narrative in Paris, then one in Istanbul, then one in Agia Galini, then one in Amsterdam, then another in Istanbul, and so on. The protagonist’s financial support? A bit of savings and a small loan from Mom — no wandering aristocrat, she. Her cultural armory? Copies of The Interpretation of Dreams, The Quiet American, and My Gun is Quick, and a love of Chantal Akerman and Luis Buñuel.

Despite her intriguing taste in books and films and merciless drive toward perpetual flight, this woman reveals remarkably little about herself. Yes, we’ve all read narrators who do and say much while concealing even more, but Tillman somehow casts aside even our standard desire to get further into her interior. A swirl of secondary characters, almost all compulsive travelers with a tendency to turn up in several different nations, offers a distraction: our heroine helps an aged eccentric assemble her memoirs, signs on to a tour of aggressive sightseeing with a pair of English brothers, drinks with an ill-fated ex-cop, separately encounters a Buddhist American single mother and her runaway husband, and falls for a Yugoslavian who argues, with increasing strenuousness, for the melancholic weight of history that supposedly hunches all Europeans.

But does this supporting cast counterbalance the failure to probe of the narrator’s deeper character, or do the countless, always-developing nuances of her various relationships with them constitute her deeper character? Haunting cafés with one, momentarily shacking up in a rented room with another, writing postcards to many others but tearing most of them up — these actions, and nothing else, could prove enough to make a human being. “In a sociology course I took the professor said that what we call personality doesn’t exist except in relation to others,” Tillman, with an uncharacteristic explicitness, has her protagonist say toward the book’s end.

In Cast in Doubt, Tillman creates Horace, another traveler whose gender alone makes him feel at first like a stark departure. But his homosexuality emerges in the early chapters, either bringing him closer to or distancing him from his lady colleagues in the Tillman oeuvre. The relevant question: what do male homosexuality and female heterosexuality have in common — a lot, or nothing? If Horace doesn’t approach this issue directly, he at least takes on questions in its orbit when he develops a controlling aesthetic-intellectual infatuation with a girl who one day lands in his tiny Greek town.

In Cast in Doubt, Tillman creates Horace, another traveler whose gender alone makes him feel at first like a stark departure. But his homosexuality emerges in the early chapters, either bringing him closer to or distancing him from his lady colleagues in the Tillman oeuvre. The relevant question: what do male homosexuality and female heterosexuality have in common — a lot, or nothing? If Horace doesn’t approach this issue directly, he at least takes on questions in its orbit when he develops a controlling aesthetic-intellectual infatuation with a girl who one day lands in his tiny Greek town.

Horace, you see, has long since gone expat. At 65, shacked up on Crete with a surly twentysomething local, he tosses off crime potboilers while avoiding work on a hazy magnum opus called Household Gods. When Helen — surely the most loaded possible name, given the Greek context — enters his life, his hypertrophied fictionalist’s mind builds around her a towering mystique. Though the objective details portray Helen as nothing more than a callow, flighty psychiatrist’s daughter with a loopy scrapbook in hand, Horace looks at her and practically gets vertigo. Needless to say, her disappearance, which comes as suddenly as her arrival, only intensifies his obsession.

Beneath Cast in Doubt’s stolidly un-flashy surface, Tillman uses Helen’s draw on Horace to perform a fascinating act of genre subversion. Horace funds his self-imposed exile by writing the surprisingly inventive yet still groan-inducing exploits of detective Stan Green, and Horace looks to Green as his model when he resolves to drive across the island in pursuit of his quasi-muse. But Tillman very nearly sets the issue of whereabouts entirely aside, focusing instead on who-abouts. Soon after dedicating himself to his investigation, Horace comes to realize how little he ever knew about Helen. This doesn’t stop him from speculating, sometimes wildly, which enriches the inevitable collision of his imagination and reality — reality coming in the form of that diary in which Helen scribbled so purposefully.

Parts of the book play as a detective tale; other parts play as a standard psychological narrative; most parts play as a genre less easy to pin down. Horace’s way with stories, the remote setting to which he relegates himself, the hodgepodge cast that surrounds him — a South African provocateur; a black New York “scenemaker”; a former opera star, a limp, cynical aesthete; a hirsute English hermit — and the reigned scowl underlying even his happier moments all remind me of David Markson’s Going Down. What can we call this tiny genre? I suggest “oblique, vaguely menacing narratives of fictional complacent expatriate writers.” Barnes & Noble can start building that shelf any day now.

4. What every malcontent needs

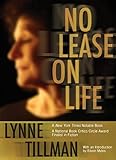

If it weren’t for all the jokes, No Lease on Life would read as yet another story of crushing rent-controlled New York squalor. When Tillman writes squalor, she writes squalor: layer upon layer of grime; collapsed, immobile junkies; heaping piles of human waste; slashed bags of garbage; spreading pools of milk. And that’s just inside Elizabeth Hall’s building! In the first half of the book, Tillman recounts Elizabeth’s battles to nail down an apartment in New York, to fight a minute rent increase, to get her drunken superintendent to clean anything at all, to convince the guy across the street to quite revving his car so early in the morning — all in the course of one night.

If it weren’t for all the jokes, No Lease on Life would read as yet another story of crushing rent-controlled New York squalor. When Tillman writes squalor, she writes squalor: layer upon layer of grime; collapsed, immobile junkies; heaping piles of human waste; slashed bags of garbage; spreading pools of milk. And that’s just inside Elizabeth Hall’s building! In the first half of the book, Tillman recounts Elizabeth’s battles to nail down an apartment in New York, to fight a minute rent increase, to get her drunken superintendent to clean anything at all, to convince the guy across the street to quite revving his car so early in the morning — all in the course of one night.

Transfixed by the sweep of street chaos on her block, Elizabeth stares out the window instead of sleeping, fantasizing about taking up a crossbow to murder the “morons” and “crusties” vomiting and knocking over trashcans all night long. Tillman evokes an almost farcically shambolic New York familiar to anyone who enjoys the literature and film that came from the city in the seventies, but she sets this novel in 1994 — you can tell by the O.J. trial references — thus illustrating that the place didn’t go completely minty-fresh in the nineties. Or at least Elizabeth’s block — her world — didn’t.

When I talk about No Lease on Life’s “jokes,” I don’t necessarily mean that Tillman or Elizabeth, despite the grit-toothed resolve evident in the both of them, lighten these circumstances with the cynical wit every educated lowish-class urban malcontent needs. Besides the line between the book’s two days, which bear the titles “Night and Day” and “Day and Night”, only jokes break up the text. Common, punchline-y, sometimes tired, often sexual or racial jokes, none of which, miraculously, have an explicit relationship to the narrative. I happened to laugh the loudest at this one, which also bears an unusual thematic relevance:

A man who lived in New York City couldn’t stand it any more. So he moved to Montana. His closest neighbor was ten miles away. The first month was great — he didn’t see anyone. It was quiet. After three months he started to get restless. After six months he was so bored, he thought about moving back to the city. A neighbor called. He invited him to a party. The neighbor said, get ready for a lot of drinking, fighting, and fucking. Great, the man said. Who’ll be there? You and me, the neighbor said.

In American Genius: A Comedy, Tillman brings strands of Elizabeth, Emily, Grace, Jane, and the others into a single consciousness, allowing us unprecedented entry. But do we enter it, or does it entrap us? Not until a hefty chunk of pages has passed does Tillman reveal the name of Helen, the novel’s central character and one who has voluntarily entrapped herself in some sort of colony or low-security institution. Though she rarely roams far from wherever it is she lives, her thoughts spread, soar, and loop — especially loop — through subjects and variations on the industrial technology of textiles, the Zulu language, former Manson acolyte Leslie van Houten, and dermatology — especially dermatology.

In American Genius: A Comedy, Tillman brings strands of Elizabeth, Emily, Grace, Jane, and the others into a single consciousness, allowing us unprecedented entry. But do we enter it, or does it entrap us? Not until a hefty chunk of pages has passed does Tillman reveal the name of Helen, the novel’s central character and one who has voluntarily entrapped herself in some sort of colony or low-security institution. Though she rarely roams far from wherever it is she lives, her thoughts spread, soar, and loop — especially loop — through subjects and variations on the industrial technology of textiles, the Zulu language, former Manson acolyte Leslie van Houten, and dermatology — especially dermatology.

Helen: we’ve heard that name before. Could the mind of this middle-aged American History PhD. exiled from the greater social sphere belong to the very same Helen of Cast in Doubt, thirty years on? Or to one of the now very much grown girls of Haunted Houses? Or to the traveler of Motion Sickness, who finally learned a way to stay put and then some? Tillman prevents us from firmly believing or rejecting any or all of those possibilities. I can imagine any of her main characters at home here, wrapped in this oversensitive skin and oversensitive consciousness, reacting in vast paragraphs to this community of disparate eccentrics, ready at any moment to see and build upon the patterns in the seemingly yet deceptively formless play of data, ideas, and recollections that combination sparks.