1.

In the preface to his collection of stories In the Heart of the Heart of the Country, William H. Gass imagines for himself a reader. He will be “skilled and generous with attention, for one thing,” Gass writes, “patient with longeurs, forgiving of every error and the author’s self indulgence, avid for details.” Gass doesn’t stop there:

In the preface to his collection of stories In the Heart of the Heart of the Country, William H. Gass imagines for himself a reader. He will be “skilled and generous with attention, for one thing,” Gass writes, “patient with longeurs, forgiving of every error and the author’s self indulgence, avid for details.” Gass doesn’t stop there:

…ah, and a lover of lists, a twiddler of lines. Shall this reader be given occasionally to mouthing a word aloud or wanting to read to a companion in a piercing library whisper? yes; and shall this reader be one whose heartbeat alters with the tense of the verbs? that would be nice…

Eventually, Gass conjures a reader without a body: only lips for mouthing the words, and eyes for reading them, and perhaps a finger to hold down the page. “Let’s imagine such a being, then,” Gass writes. “And begin. And then begin.”

I’ve shown this passage to students before asking them to create their own ideal readers. Most new writers don’t like to imagine anyone actually reading their work–the idea is either preposterous or terrifying, or both–and this exercise forces them to do just that. From now on, there is an audience. An ideal reader, thankfully, is interested in what you’re interested in, delights in what you delight in, and thus reads your work eagerly, and with compassion. That’s not to say they’re your mindless yes-man, either (well, mine isn’t–though Gass’s might be). As much as my ideal reader inspires and motivates me, she also keeps me honest. That woman, she’s a tough cookie! I want to entertain, beguile, discomfit and move her. I’m beholden to her.

This reminds me of an interview with Kurt Vonnegut that I heard on NPR a few years ago. He said he wrote everything for his deceased sister. She was his intended audience whether or not she was alive to read his work. I think this a beautiful and noble reason to return to one’s desk every morning, don’t you? Or, let’s be honest: it’s a reason, period.

2.

Not all of my readers are imaginary. My husband reads everything I write multiple times (why he hasn’t filed for divorce yet, I don’t know), and I have a few friends with whom I exchange work on a semi-regular basis. As with my fictionalized readers, I feel a modicum of safety with these real ones, as well as a desire to 1. Surprise them. 2. Not bore them. And, 3. Make them feel something complicated, maybe even transcendent. Without these reading relationships, I would be a much worse writer. And, honestly, I’m not sure writing would feel as necessary as it does to me.

Sometimes I think the best gift I could give a student would be a classmate who truly gets their writing. After the class ends, they could go off on their own, and carry on a friendship that would hopefully last years, manuscripts. I have such a friendship with a poet I’ll call Alice. We don’t exchange work often, but we’re big fans of each other’s writing, and we understand the other’s voice and vision of the world.

Recently, Alice sent me some prose, which she had originally written for another friend. Alice had written the piece for her friend’s birthday, with her friend in mind; the writing itself was the birthday gift. I loved this idea, but in an email Alice expressed her concerns:

I sometimes like to give myself little assignments to write something for a very particular audience–rather than the ambiguous, ambivalent “world”–it helps me to return to a more generous and playful place in my poems. I don’t know. Perhaps these small acts of “publishing,” a story sent to a friend on her birthday, a poem written for a wedding, reveal a lack of ambition–or perhaps deep fear of real, acknowledged failure. Maybe keeping the stakes so low is cowardly. Perhaps bravery must hold hands with generosity, and in that, real genius.

I don’t totally agree. After all, Alice’s prose was not intended for me, and yet I still enjoyed it. Just because a piece of art is made for one particular person doesn’t mean it can’t be consumed and adored by others. And narrowing the “ambiguous, ambivalent” world into one person is, in its own way, daring. In his “Thirty-Two Statements About Writing Poetry,” Marvin Bell suggests writing poems that at least one person in the room will hate; that seems easier than writing poems that only one person in the room will love. Pleasing a single idiosyncratic reader is indeed an act of generosity, and if that will liberate you and open you up to artistic risk, then I say: Why question it?

Of course, Alice might have a point. She doesn’t submit her work; for the past couple of years, she has kept the stakes low by only sharing her poems with friends. Her aesthetic ambition soars, but without the acknowledgment of, and engagement with, a larger audience of readers, one could argue that she’s playing it safe.

3.

I’ve been wondering a lot about how sharing one’s writing with a larger audience alters one’s process–how having multiple readers, a potential world of them, can strengthen that process, and challenge it, and how it can also, if you aren’t careful, wound and compromise it. A few more-seasoned writers than I have advised me to try to finish my second novel before the first one is published. After all, once a writer’s first book comes out, she has expectations to live up to or defy, she has a body of work to build upon, she has an identity to answer to. Before that, she’s just a writer in her garret, sharing her words with one imaginary reader and perhaps her husband and a handful of friends. There is freedom in being unknown; you’ve still got your shimmering potential to keep you warm at night.

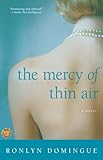

Ronlyn Domingue’s refreshingly honest essay about receiving a horrible review of her first novel The Mercy of Thin Air in the New York Times has stayed with me since I read it over a year ago. Her experience is one any writer would struggle with. Perhaps it’s the very threat of this kind of rejection and criticism that my friend Alice fears. But Domingue’s conclusion is wise:

Ronlyn Domingue’s refreshingly honest essay about receiving a horrible review of her first novel The Mercy of Thin Air in the New York Times has stayed with me since I read it over a year ago. Her experience is one any writer would struggle with. Perhaps it’s the very threat of this kind of rejection and criticism that my friend Alice fears. But Domingue’s conclusion is wise:

Although the advice to have a thick skin was well-meant, it is emotionally dishonest. Sharing one’s writing is a naked act not intended for the meek. Harsh words can—and sometimes do—undermine the most confident, successful writers. It’s human. It’s okay. It will pass. Now, my guidance to myself, and others, is to have a permeable skin, one that doesn’t resist or trap the good or the bad. Reviews, critiques, comments come in, then move on. Then there’s space, inside and out, for something new.

The opportunity for “something new” is created, I think, by a readership.

4.

This may sound silly, but before my novella If You’re Not Yet Like Me came out, I didn’t anticipate what it might feel like to have readers respond to it. I had no idea how biographically (and, in some cases, autobiographically), the readers I know personally would read my writing. An old friend thought the main character was a lot like her; her ex-boyfriend admitted to me in an email that he saw himself in the main character’s love interest. My brother, who mistakenly believes he has big hips, wanted to know why I had to rag on men who “gain weight like a woman does,” as if I were my narrator. A former coworker thought the story of Joellyn and Zachary’s failed romance was a parallel story of me and my husband, had things gone awry. My closest friend listed all the elements of the story I’d taken from my own life–and she was accurate.

My mother said that my book was “good”–and she only volunteered this laconic response after I’d asked for one. I guess my face fell at her unconvincing tone, and she said, “What am I supposed to say? Oh, Edan, you’re so talented!” Um–maybe? I suppose, since she’s an avid reader, that I’d hoped we might have an in-depth conversation about the text, and that she might share observations that I hadn’t considered when writing it.

But–wait–is that true? My mother is one reader that I purposefully don’t consider when writing, for fear of how her spectral presence might censor me. Lorrie Moore has told her students to write something they’d never show their mother or father, and that’s sound advice if you want to write freely. But when an “orphaned” writer publishes said book, she must contend with these readers. Victoria Patterson wrote about this very experience for The Millions last year. Of her mother’s response to her short story collection, she said:

Despite my apologies (“I never meant to hurt you, that wasn’t my intention; no one wants to hurt their mother!”), and my insistence on the fictionalized nature of the stories, my mom continues to feel deeply wounded, and she vocalizes it, especially after a few glasses of wine—lashing me with guilt. Yet she keeps a file with all my reviews and articles, and has given copies of Drift to her friends

That’s more tame than Gina Frangello’s account of her mother-in-law’s outrage at her first novel, My Sister’s Continent:

What I know a little something about could only be called the interpersonal consequences of trying to write with emotional honesty. The way we writers stretch ourselves out on the line, inviting grudges, inviting a fight. The way I discovered I hated to fight (how had this happened? I’d kicked my share of little-girl-ass back in the hood when I was a kid. But my temper, it seemed, had been “gentrified,” and I realized, more than anything else, that I had left the environment of my youth not for a bigger house or even an advanced degree, but because I wanted to be able to live without violence) . . . yet even this being true, I would continue to put my neck out to the blade of others’ criticism or anger when writing. I would continue to write as if everyone I had ever known was already dead, even though they were not, and even knowing there could be reckoning.

Neither Patterson nor Frangello regret their work, no matter the pain it might have caused these readers. As Frangello says, “Writing is risk. If you don’t feel that when you’re writing, for god’s sake stop.” Part of that risk is offending those who might not want to venture into your imagination. Maybe I foolishly long for an extreme response from someone close to me, for it means that reader has been truly affected by my work. When I re-read Patterson’s essay, I thought, My father hasn’t even read my book. I’ve realized that another challenge of readership is that some members of your audience aren’t paying attention.

5.

As has been advised, I’m working on a new novel now. The way things are going, it will certainly be done (a good draft at least) before my first one is published. When I head to my desk, I think of my ideal reader–slathering butter on French bread as she reads, greasing up the page. She’s got the window open, as she likes the breeze on her face, and maybe there’s some music playing softly in the other room. I think of my husband, who loves a good campus novel, and of my writer-friend Madeline, who delights in an acrobatic sentence. I think of Alice, who will help me name the trees in this book, and who I hope will someday write a poem for me and me alone.

There are many, many people I won’t think about. They’ve been banished from the garret. But only for now.

(Image: bunker: light-door of hope ? from frenchy’s photostream)