A few weeks ago, a friend of mine posted a goodreads review of Jennifer Egan’s A Visit from the Goon Squad. In it, he wrote that he wished books with more than 10% of “teenage girl content” came with an advisory warning. This way, he could avoid them. This was puzzling to me. If a book had a label that said, “Warning! Teenagers Inside!” I would be more likely to pick it up. Doesn’t every reader, male or female, young or old, find that phase of life to be particularly dramatic, moving, screwed up, and beautiful? I loved the teenagers that populated Egan’s latest novel, especially Rhea, who narrates the chapter/story “Ask Me if I Care,” and not only because she’s a freckle-face like I was (am). She’s vulnerable and wise, and also incredibly naive, too. Her desires are painfully strong, and yet she cannot totally understand them.

A few weeks ago, a friend of mine posted a goodreads review of Jennifer Egan’s A Visit from the Goon Squad. In it, he wrote that he wished books with more than 10% of “teenage girl content” came with an advisory warning. This way, he could avoid them. This was puzzling to me. If a book had a label that said, “Warning! Teenagers Inside!” I would be more likely to pick it up. Doesn’t every reader, male or female, young or old, find that phase of life to be particularly dramatic, moving, screwed up, and beautiful? I loved the teenagers that populated Egan’s latest novel, especially Rhea, who narrates the chapter/story “Ask Me if I Care,” and not only because she’s a freckle-face like I was (am). She’s vulnerable and wise, and also incredibly naive, too. Her desires are painfully strong, and yet she cannot totally understand them.

Teenagers have a real drive to be independent, to discover and define (or defy) their identities. And yet, they’re also powerless. They have their parents’ will to contend with, and their friends’ complicated codes of behavior. They have the secret shames of the body. They long for the purity and ease of childhood even as they fling themselves into the dangers of adulthood. In short, they make for compelling characters.

Books about teenage boys, it seems to me, are often about a rage that is hard to control and understand. Jim Shepard’s Project X is a fine example of the genre. About a Columbine-style act of school violence, and the two eighth grade boys who perpetrate it, the novel is engrossing, compassionate, and oddly mundane in its faithful depiction of contemporary American adolescence. Whenever I think of Go-gurts, I think of this book.

Books about teenage boys, it seems to me, are often about a rage that is hard to control and understand. Jim Shepard’s Project X is a fine example of the genre. About a Columbine-style act of school violence, and the two eighth grade boys who perpetrate it, the novel is engrossing, compassionate, and oddly mundane in its faithful depiction of contemporary American adolescence. Whenever I think of Go-gurts, I think of this book.

I haven’t yet read Patterns of Paper Monsters by Emma Rathbone, but I want to. Narrated by seventeen year-old Jacob Higgins, who is sent to a juvenile correctional facility for committing a violent crime, the book has been described as sad and funny, and The Daily Beast promises “there’s no sappy uplift here.” At The New Yorker Book Bench blog, Eileen Reynolds writes that Jacob, “may be cut from the same cloth as Holden Caulfield, but he’s a good bit funnier and a lot less mopey than the angsty adolescent male narrators from many coming-of-age books that have followed Catcher in the Rye.” He sounds like a narrator I could fall in love with.

Though I like books about teenage boys, I prefer to read about teenage girls, most likely because I used to be one myself. Man, if I had been the narrator of a novel! What a weird and exhilarating book that would be! (See also: mortifying). I recently finished a novel manuscript about an adult woman looking back on her 16 year-old self. I (mostly) avoided reading books about similar milieus while I was writing it (for fear of undue influence), but I did, from time to time, consider some of my favorite teenage heroines. Here are just a few:

Jane Eyre. According to a footnote in my edition, Charlotte Bronte’s novel about the poor, unloved orphan who falls for that creep Mr. Rochester is probably the first occurrence of a first-person narration by a child in British literature. Perhaps that’s what renders this book so intimate and authentic. Jane is a complex, independent woman, and her storytelling is modern and hyper-conscious. I’ve always loved Jane’s bookishness, her honesty, and her plain looks. It’s her evolution from child to woman that provides us with a panoramic understanding of her character.

Jane Eyre. According to a footnote in my edition, Charlotte Bronte’s novel about the poor, unloved orphan who falls for that creep Mr. Rochester is probably the first occurrence of a first-person narration by a child in British literature. Perhaps that’s what renders this book so intimate and authentic. Jane is a complex, independent woman, and her storytelling is modern and hyper-conscious. I’ve always loved Jane’s bookishness, her honesty, and her plain looks. It’s her evolution from child to woman that provides us with a panoramic understanding of her character.

Mick Kelly. It’s been a long time since I’ve read The Heart is a Lonely Hunter by Carson McCullers. I have a terrible memory, but this novel’s teenage protagonist is never really far from my mind. Mick dresses like a boy. She feels trapped in her small Southern town. She is composing a symphony in her head called “This Thing I Want, I Know Not What.” That phrase…God, it’s haunted me for years.

Thisbe Casper. Thisbe is the younger of the two teenage daughters in Joe Meno’s most recent novel, The Great Perhaps. She’s a fervent believer in God among a family of nonbelievers, and she also has a crush on her friend Roxie, which fills her with fear and shame. She’s aglow with all kinds of feelings, and I adore her. It’s no surprise that Thisbe was Meno’s favorite character in the book.

Thisbe Casper. Thisbe is the younger of the two teenage daughters in Joe Meno’s most recent novel, The Great Perhaps. She’s a fervent believer in God among a family of nonbelievers, and she also has a crush on her friend Roxie, which fills her with fear and shame. She’s aglow with all kinds of feelings, and I adore her. It’s no surprise that Thisbe was Meno’s favorite character in the book.

Chloe from Charles Baxter’s The Feast of Love. The Feast of Love was on my list of favorite books of the decade, partially because of Chloe’s sections, which are narrated with a raw, kinetic energy. Chloe’s boyfriend is pierced-up Oscar with “the blond hair, the snaggle-toothed smile, the bomb-shelter eyes.” I’m not sure how old Chloe is (if it said in the book, I don’t remember), but she seems about nineteen to me — she’s got that reckless hopefulness in her. At the beginning of her first section, she says of her and Oscar, “We were swoon machines,” and I, the reader, swoon myself. I love that Baxter marries colloquialisms and cliche with striking, unique turns of phrase to get at a teenager’s way of moving through the world.

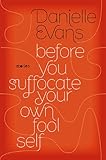

I’ve recently started Before You Suffocate Your Own Fool Self by Danielle Evans, a debut collection of stories about young African-American women (some of them teenagers) living on the east coast. In her laudatory review in the New York Times, Lydia Peelle writes, “Rather than limiting the collection’s gaze, this perspective amplifies the universal pitfalls of coming of age in 21st-century America.” I’ve only read the first story, “Pilgrims,” but the conflicts therein already support Peelle’s thesis. In a scene between the high school-aged narrator, her friend Jasmine, and some older guys they’ve met a club, there’s one finely-wrought moment. The girls have, of course, lied about their age:

I’ve recently started Before You Suffocate Your Own Fool Self by Danielle Evans, a debut collection of stories about young African-American women (some of them teenagers) living on the east coast. In her laudatory review in the New York Times, Lydia Peelle writes, “Rather than limiting the collection’s gaze, this perspective amplifies the universal pitfalls of coming of age in 21st-century America.” I’ve only read the first story, “Pilgrims,” but the conflicts therein already support Peelle’s thesis. In a scene between the high school-aged narrator, her friend Jasmine, and some older guys they’ve met a club, there’s one finely-wrought moment. The girls have, of course, lied about their age:

“Man, look who we got here,” said the one in the passenger seat, turning around. “College girl with a attitude problem. How’d we end up with these girls again? Y’all are probably virgins, aren’t you?”

“No,” Jasmine said. “Like hell we are. We look like virgins to you?”

“Nah,” he said, and I didn’t know whether to feel pissed off or pretty.

This exchange captures so well what it feels like to be that age: wanting approval, and respect, and also wanting to be desired, even if you don’t feel that desire back. I’m looking forward to reading the rest of Evans’s stories, to see how she deepens her exploration of this puzzling and complex demographic. Something tells me she will.

Writing this almost makes me want to write another book about a teenager. Almost — it’s not easy, throwing yourself into that world again. But I could read dozens of books about teenagers. Dozens! And those warning stickers? They’d help.