Oh, what a vileness human beauty is,

Corroding, corrupting everything it touches.

–Euripides, Orestes, 126-7

With such painstaking awe is the beauty of The Red and The Black’s Julien Sorel detailed that one might think Stendhal was describing a woman. We are treated to countless descriptions of Julien’s “fine complexion, his great black eyes, and his lovely hair, which was curlier than most men’s…” We learn that his eyes sparkle with hatred when he is angry, and indicate thought and passion when he is at peace. “Among the innumerable varieties of the human face, there may well be none more striking,” Stendhal suggests, almost matter-of-factly.

With such painstaking awe is the beauty of The Red and The Black’s Julien Sorel detailed that one might think Stendhal was describing a woman. We are treated to countless descriptions of Julien’s “fine complexion, his great black eyes, and his lovely hair, which was curlier than most men’s…” We learn that his eyes sparkle with hatred when he is angry, and indicate thought and passion when he is at peace. “Among the innumerable varieties of the human face, there may well be none more striking,” Stendhal suggests, almost matter-of-factly.

In The Greater Hippias, Plato argues that beauty is good and the good is beautiful: the two are identical. Superficial though the ancient Greeks might have been, even later Christian philosophers like Castiglione held that only rarely does an evil soul dwell in a beautiful body, and so outward beauty is a true sign of inner goodness.

Stendhal would have agreed. With Julien’s high Napoleonic ideals and his violent, even physiological, reactions to all things base or hypocritical, he has “a soul fashioned for the love of beauty.” But life does not turn out so well for this young romantic because, predictably, Julien “was barely a year old when his beautiful face began to make friends for him, among the little girls…”

Fictional characters enjoy exaggerated attributes, but few have the sort of beauty that marks Julien Sorel, where the beauty is not only essential to his character, elevating his soul, but outside of it, dictating his destiny. If beauty can be distilled from its specific fictional forms, does it have a cogent power of its own in literature?

1. The Most Beautiful Woman in Fiction

If there were ever a fictional beauty contest of sorts, the stand-out winner might very well be Remedios the Beauty from 100 Years of Solitude. Naive to the point of saintliness, Remedios the Beauty unintentionally causes the deaths of several men who lust over her. But despite being entirely uninterested in feminine wiles, dressing in course cassocks, and shaving her head:

If there were ever a fictional beauty contest of sorts, the stand-out winner might very well be Remedios the Beauty from 100 Years of Solitude. Naive to the point of saintliness, Remedios the Beauty unintentionally causes the deaths of several men who lust over her. But despite being entirely uninterested in feminine wiles, dressing in course cassocks, and shaving her head:

…the more she did away with fashion in a search for comfort and the more she passed over conventions as she obeyed spontaneity, the more disturbing her incredible beauty became…

Under the Platonic model there is a “scale of perfection ranging from individual, physical beauty up the heavenly ladder to absolute beauty.” And in that lofty vein, Garcia Marquez describes Remedios the Beauty as though she were beauty manifest, in too pure a form for this Earth, and she leaves her novel by mysteriously ascending to the sky, like a spirit.

What exactly was it that made Remedios the Beauty so “disturbingly” beautiful? For one, it had very little to do with the worldly practice of seduction. Writes Neal Stephenson (about another beautiful character) in The System of the World:

What exactly was it that made Remedios the Beauty so “disturbingly” beautiful? For one, it had very little to do with the worldly practice of seduction. Writes Neal Stephenson (about another beautiful character) in The System of the World:

Faces could beguile, enchant, and flirt. But clearly this woman was inflicting major spinal injuries on men wherever she went, and only a body had the power to do that. Hence the need for a lot of Classical allusions… Her idolaters were reaching back to something pre-Christian, trying to express a bit of what they felt when they gazed upon Greek statues of nude goddesses.

Still, the ascending beauty of Remedios the Beauty struck me as close to paradoxical. She might have been beauty in essence, but her absolute beauty was something she achieved, namely, by renouncing her beauty through eschewing feminine clothing and, more vividly, shaving her head.

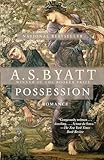

There is a curious relationship between hair and destiny in literature. Chaucer, like Hollywood, is known for casting women by their hair color, but he is far from the exception. In keeping with the practices of Remedios the Beauty, the most reputable beautiful women in fiction part ways with their hair altogether at some point, such as Maria “the cropped headed one” in For Whom The Bell Tolls (whose name is an arguable allusion to the Virgin Mary by Hemingway), or Janie in Their Eyes Were Watching God, who hides her hair under a rag for much of her life (and is reputable to her readers, if not always to the townsfolk of Eatonville). Even fictional literary scholar Maud Bailey from A.S. Byatt’s Possession picked up on the strange connection between hair and destiny for beautiful women: she kept her head nearly shaved in her early teaching days, recounting Yeats’ “For Anne Gregory”:

There is a curious relationship between hair and destiny in literature. Chaucer, like Hollywood, is known for casting women by their hair color, but he is far from the exception. In keeping with the practices of Remedios the Beauty, the most reputable beautiful women in fiction part ways with their hair altogether at some point, such as Maria “the cropped headed one” in For Whom The Bell Tolls (whose name is an arguable allusion to the Virgin Mary by Hemingway), or Janie in Their Eyes Were Watching God, who hides her hair under a rag for much of her life (and is reputable to her readers, if not always to the townsfolk of Eatonville). Even fictional literary scholar Maud Bailey from A.S. Byatt’s Possession picked up on the strange connection between hair and destiny for beautiful women: she kept her head nearly shaved in her early teaching days, recounting Yeats’ “For Anne Gregory”:

Never shall a young man

Thrown into despair

By those great honey-coloured

Ramparts at your ear

Love you for yourself alone

And not your yellow hair.

But Julien Sorel never made such sacrifices. It would be most remiss to compare him to the saintly Remedios the Beauty, as he dabbles in vanity, employs manipulative mind-games, and continuously – though not malevolently – makes full use of his preternatural sex appeal in pursuit of his romantic ambitions. Rather, Julien is far better suited to a category of characters with a starkly different literary reputation…

2. The Second Most Beautiful Woman in Fiction

Notable beautiful women with such a lust for life include Flaubert’s Madame Bovary, who “had that indefinable beauty that results from joy, from enthusiasm, from success” and Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina, with her “mysterious, poetic, charming beauty, overflowing with life and gayety…” But the most beautiful of all is The Return of the Native’s Eustacia Vye:

Notable beautiful women with such a lust for life include Flaubert’s Madame Bovary, who “had that indefinable beauty that results from joy, from enthusiasm, from success” and Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina, with her “mysterious, poetic, charming beauty, overflowing with life and gayety…” But the most beautiful of all is The Return of the Native’s Eustacia Vye:

Eustacia Vye was the raw material of a divinity… Her presence brought memories of such things as Bourbon roses, rubies, and tropical midnights; her moods recalled lotus-eaters… her motions, the ebb and flow of the sea; her voice, the viola. In a dim light… her figure might have stood for one of the higher female deities…

Eustacia’s textual description is not exactly an exercise in restraint. On Hardy goes for two pages, describing the curve of her lips, her “pagan” eyes, the weight of her figure – and two paragraphs alone devoted to the sheer bounty of her dark hair, of which “a whole winter did not contain darkness enough to form its shadow.”

Like Julien Sorel, Eustacia Vye is naive, egotistical, self-serving, and obsessed with the idea of Paris, “the centre and vortex of the fashionable world.” She is far too human to achieve the Platonic ideal of beauty, “transcending sex, sensuality and ‘mere’ physical beauty” to “the region where gods dwell.” Nevertheless, Hardy gives a nod to “the fantastic nature of her passion, which lowered her as an intellect, raised her as a soul.”

And like Julien Sorel, Anna Karenina, and Emma Bovary, Eustacia – mired by the societal constraints on her free will – ponders:

But do I desire unreasonably much in wanting what is called life – music, poetry, passion, war, and all the beating and pulsing that is going on in the great arteries of the world?

3. The Curse of Beauty

The short answer: Yes. Without question. All four romantic leads bring about varying degrees of generalized suffering and to some degree their own demise, whether in gruesome and painful detail, like Emma Bovary, or only in critical speculation, like Eustacia. In literature, as it turns out, it is dangerous to be ambitious just as it is dangerous to be beautiful, but to be both ambitious and beautiful is fatal.

Helen of Troy is the prototypical example that ancient aesthetic philosophy ascribed a darker tone to female beauty than it (generally speaking) did to male beauty. Historian Bettany Hughes writes, “Rather than positioning Helen’s beauty as a worthy gift of the gods – ancient authors… saw her peerless face and form as a curse.” And yet, the power of Julien’s beauty proves to be as inevitably corrosive in The Red and The Black as it does in the respective novels of our beautiful female characters.

In fact, that sheer absence of a double standard to a great extent saves The Red and The Black from losing its modern flavor. As P. Walcot acknowledges the ancient Greek belief in “the male’s inability to resist… the immense power that the female wields through her sexuality,” so, too, are Julien’s female admirers Madame de Rênal (despite being married!) and Mathilde de La Mole (despite being solely motivated by boredom!) judged equally helpless in succumbing to their desire for him.

In part this arises from an amount of sympathy that Stendhal clearly harbored for women (he apparently had a beloved sister), even wealthy, spoiled, bored young women like Mathilde: in reference to her, he quotes from the Memoirs of the Duke d’Angouleme, “The need of staking something was the key to the character of this charming princess… Now, what can a young girl stake? The most precious thing she has: her reputation.”

Julien Sorel, conversely, escapes Stendhal’s goodwill far longer. From Diane Johnson’s introduction to The Red and the Black:

This accounts for the side of Julien that is calculating, flattering, insincere, and inwardly hostile even to people who intend to help and love him – indeed, he is an early example of an anti-hero of whom, at first, even Stendhal cannot approve. (emphasis added)

4. The Cure of Youth

At first.

But The Red and The Black has an unexpected twist: Julien gets to die like a martyr. There is hardly a consensus on this interpretation, but I read his death as something akin to a happy ending. Julien somehow manages to give everyone what they want from him – in particular, his most affected conquests. He returns the pious Madame de Rênal’s love and fulfills the passionate Mathilde’s Gothic fantasies while (outwardly) rejecting neither of them. But more amazingly: he reaches a sort of inner peace. He listens to his own heart which – unbelievably – instructs him to be truthful, sincere, to love the woman who most deserves it, and to carry the sole blame and make the entirety of amends for all the misfortune his (prior) self-indulgent, romantic nature hath wrought. Rather than marking a fundamental lack of character, Julien’s selfishness can be dismissed as mere youthful indiscretion.

Having sought the mystery behind the divergent destinies of Julien and his beautiful female counterparts in terms of the role of beauty in fiction, I come to find that it resolves itself in another, altogether more disconcerting thesis: that perhaps the nature of the young romantic hero in literature is eventually malleable, whereas the nature of the young romantic heroine in literature is essentially fixed.

Towards the end of her life, it occurs to Anna Karenina, “I am not jealous, but unsatisfied…” Emma Bovary and Eustacia Vye have similar exits: their earthly desires resist satiation, but congeal and turn ever more destructive. Their three fates recall the following canto from Dante’s Inferno, which warns of a female beast:

And has a nature so malign and ruthless,

That never doth she glut her greedy will,

And after food is hungrier than before.

And so beautiful women in literature are brought to ultimately ugly ends.