Ghostwriting used to be book publishing’s dirty little secret. A vaguely disreputable art, it was practiced quietly on the back streets of the business’s shadier precincts. The term itself speaks to a desire for privacy and anonymity—ghosts were invisible and, for the most part, happy to stay that way.

No more. Today a growing cadre of writers are discovering that checking their ego at the door and telling someone else’s story can make them very successful, very rich and, in at least one case, as close to happy as most writers will ever get.

Meet Michael D’Orso, the happy ghost.

“I bristle at the term ‘ghostwriter,'” says D’Orso. “It indicates dishonesty. It indicates hiding behind the scenes. I prefer collaborator. I’m not a shill.”

Fair enough. D’Orso, a former newspaperman, has collaborated on 10 books with subjects ranging from a U.S. senator to an inner-city principal, a fitness guru, an amateur genealogist, a professional football player and a civil rights icon. He has also written five non-fiction books on his own, on such topics as the enclave of expats on the Galapagos Islands and a disappearing tribe of native Alaskans above the Arctic circle. He has been nominated for the Pulitzer Prize six times. One of his books rose to #1 on the New York Times best-seller list and stayed on the list for more than three years. He was able to quit his newspaper job long ago and now writes full-time in his elegant – and paid-for – 4-bedroom brick Tudor house facing the Lafayette River in Norfolk, Virginia. A workaholic by any measure, he is collaborating on two books at the moment – one with a woman named Deborah Kenny who operates four thriving charter schools in Harlem, the other with the actor Ted Danson about the world’s endangered oceans. The oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico is very much on D’Orso’s mind these days.

This track record has made him rich and has put him up there in the thin air with the most sought-after collaborators. The unofficial dean of this rarefied group is William Novak, whose 1984 mega-hit, Iacocca, alerted the publishing industry to the fact that there is so much money in ghostwritten celebrity autobiographies and memoirs that the things can’t possibly be shameful. Indeed, when Bill Clinton’s former aide George Stephanopoulos bagged Novak to pen his memoir in the late 1990s, the New York Times allowed that having a big-name collaborator has become “a mark of prestige like being seen about town with a trophy wife.” Chris Ayres, who ghostwrote Ozzy Osbourne’s memoir, told the Chicago Sun-Times: “Who you choose as your collaborator is seen as almost part of the talent of the (subject). It’s seen as a decision that’s an important part of the creative process.”

This track record has made him rich and has put him up there in the thin air with the most sought-after collaborators. The unofficial dean of this rarefied group is William Novak, whose 1984 mega-hit, Iacocca, alerted the publishing industry to the fact that there is so much money in ghostwritten celebrity autobiographies and memoirs that the things can’t possibly be shameful. Indeed, when Bill Clinton’s former aide George Stephanopoulos bagged Novak to pen his memoir in the late 1990s, the New York Times allowed that having a big-name collaborator has become “a mark of prestige like being seen about town with a trophy wife.” Chris Ayres, who ghostwrote Ozzy Osbourne’s memoir, told the Chicago Sun-Times: “Who you choose as your collaborator is seen as almost part of the talent of the (subject). It’s seen as a decision that’s an important part of the creative process.”

Madeleine Morel’s 2M Communications Ltd. in New York represents more than 100 ghostwriters. Morel, who considers herself more of a talent agent than a conventional literary agent, usually matches writers with projects that come to her from editors and other agents. “Books aren’t books anymore, they’re products,” she says. “In non-fiction you have to have a platform – somebody who has a household name, or schleps around the country giving seminars, or gets a lot of media exposure. A lot of this is dictated by the fact that we’ve all become such slaves to pop culture. It’s very unromantic.”

Madeleine Morel’s 2M Communications Ltd. in New York represents more than 100 ghostwriters. Morel, who considers herself more of a talent agent than a conventional literary agent, usually matches writers with projects that come to her from editors and other agents. “Books aren’t books anymore, they’re products,” she says. “In non-fiction you have to have a platform – somebody who has a household name, or schleps around the country giving seminars, or gets a lot of media exposure. A lot of this is dictated by the fact that we’ve all become such slaves to pop culture. It’s very unromantic.”

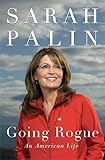

Hard words, but undeniably true. What Morel does – putting interesting (or merely famous) people together with talented storytellers to produce commercially viable books – is an equation that makes a great deal of sense for these times. Many people have intriguing life stories, and many others appeal to readers simply because of they’re famous or notorious or stylish or rich or powerful or weird. Quite often such people are incapable of writing a single coherent sentence, let alone a book. Given that, it might even be regarded as a public service that professional writers are brought in, more and more often, to help such people tell their stories. Anyone who has heard Sarah Palin talk was surely relieved to learn that she’d hired a professional writer named Lynn Vincent to ghostwrite her memoir, Going Rogue. Speaking for Palin and her husband, Vincent wrote: “We felt our very normalcy, our status as ordinary Americans could be a much-needed fresh breeze blowing into Washington, D.C.” The sentiment might make you want to blow lunch, but the sentence could have been so much worse.

Small wonder, then, that ghostwriting has officially left the ghetto. In the years since Iacocca appeared – and perhaps going back to Alex Haley’s legendary ghostwriting job on The Autobiography of Malcolm X in 1965 – the engines that drive the arts, entertainment, celebrity and technology have been working together, sometimes by accident and sometimes by design, to remove any lingering taint from the act of collaboration. As the generation weaned on computer technology takes center stage, the embrace of pastiche in all art forms is challenging the very notion of a unique artistic voice. When everything belongs to everybody, originality itself becomes a questionable proposition. After a German teenager named Helene Hegemann won rave reviews for Axolotl Roadkill, her novel about druggy Berlin club kids, a blogger pointed out that she’d lifted entire pages, almost verbatim, from another writer. Unfazed, Hegemann countered that her methods were part of the sampling culture the novel set out to capture and celebrate. The judges of a prestigious German literary prize agreed. “There’s no such thing as originality anyway,” Hegemann said, “just authenticity.”

Small wonder, then, that ghostwriting has officially left the ghetto. In the years since Iacocca appeared – and perhaps going back to Alex Haley’s legendary ghostwriting job on The Autobiography of Malcolm X in 1965 – the engines that drive the arts, entertainment, celebrity and technology have been working together, sometimes by accident and sometimes by design, to remove any lingering taint from the act of collaboration. As the generation weaned on computer technology takes center stage, the embrace of pastiche in all art forms is challenging the very notion of a unique artistic voice. When everything belongs to everybody, originality itself becomes a questionable proposition. After a German teenager named Helene Hegemann won rave reviews for Axolotl Roadkill, her novel about druggy Berlin club kids, a blogger pointed out that she’d lifted entire pages, almost verbatim, from another writer. Unfazed, Hegemann countered that her methods were part of the sampling culture the novel set out to capture and celebrate. The judges of a prestigious German literary prize agreed. “There’s no such thing as originality anyway,” Hegemann said, “just authenticity.”

It is possible to argue with that sentiment, but there’s no denying its broad appeal and growing acceptance. In such a fluid climate – and in a culture that’s pie-eyed drunk on celebrity in its glitziest and tawdriest forms – it’s not surprising that ghostwriting has won acceptance as just one of many legitimate ways to produce books. Including novels. Brand-name author James Patterson has a stable of writers helping him churn out his best-selling thrillers. The rapper 50 Cent, who must be a very busy man, pays someone to ghostwrite his 140-character tweets for Twitter. A reading public inured to fabricated journalism, fake memoirs and bald acts of plagiarism barely shrugged when word got out that Ted Kennedy had quietly worked with a ghostwriter whose name did not appear on the cover of his posthumous memoir, True Compass. The publisher insisted that the late senator was deeply involved in the writing. Such is not always the case. Some subjects’ brazen lack of involvement in their own books has become the source of loopy publishing lore. When Ronald Reagan’s memoir, An American Life, appeared, the Gipper gave high praise to his ghostwriter, Robert Lindsey. “I hear it’s a terrific book,” Reagan said. “One of these days I’m going to read it myself.” Long gone are the days when the likes of Ulysses S. Grant, Charles de Gaulle and John F. Kennedy shouted down any suggestion that they’d relied on ghostwriters to help them produce their memoirs. Such authorial integrity now seems so 19th- and 20th-century, so quaintly pre-digital.

It is possible to argue with that sentiment, but there’s no denying its broad appeal and growing acceptance. In such a fluid climate – and in a culture that’s pie-eyed drunk on celebrity in its glitziest and tawdriest forms – it’s not surprising that ghostwriting has won acceptance as just one of many legitimate ways to produce books. Including novels. Brand-name author James Patterson has a stable of writers helping him churn out his best-selling thrillers. The rapper 50 Cent, who must be a very busy man, pays someone to ghostwrite his 140-character tweets for Twitter. A reading public inured to fabricated journalism, fake memoirs and bald acts of plagiarism barely shrugged when word got out that Ted Kennedy had quietly worked with a ghostwriter whose name did not appear on the cover of his posthumous memoir, True Compass. The publisher insisted that the late senator was deeply involved in the writing. Such is not always the case. Some subjects’ brazen lack of involvement in their own books has become the source of loopy publishing lore. When Ronald Reagan’s memoir, An American Life, appeared, the Gipper gave high praise to his ghostwriter, Robert Lindsey. “I hear it’s a terrific book,” Reagan said. “One of these days I’m going to read it myself.” Long gone are the days when the likes of Ulysses S. Grant, Charles de Gaulle and John F. Kennedy shouted down any suggestion that they’d relied on ghostwriters to help them produce their memoirs. Such authorial integrity now seems so 19th- and 20th-century, so quaintly pre-digital.

Given this history, it’s easy to find much to admire in the way Michael D’Orso collaborates on a book. He had to learn the craft from scratch, and his education began one day in 1986 when he received a phone call from Jackie Onassis, then a book editor at Doubleday. She had read a newspaper article of D’Orso’s that had gotten picked up by the wire services, the story of a black social worker named Dorothy Redford who was researching her slave ancestry.

(Full disclosure: When D’Orso received that phone call, we were both working as staff writers at the Norfolk Virginian-Pilot. I had already developed great respect for D’Orso’s fierce energy, his skill as a reporter, and his ability to craft vivid sentences and narratives. After reading three of his books, my admiration has only grown.)

Initially D’Oroso was taken aback when he realized that Onassis wanted him to write a book with Redford, not a book about her. Every collaborative book he could think of was, as he puts it, “a piece of shit.” Then, remembering The Autobiography of Malcolm X, D’Orso decided to take the plunge.

“I made my own simple rules,” he recalls, speaking with the same intensity he brings to his reporting and writing. “Number one, it would truly be a collaboration. We agree to go in together and we’re not going to leave until we both agree on the final result. Number two, what the subject brings is his or her story and what I bring are my skills as a writer. I’m going to push you as far as you can go. I’m going to ask questions that go into more detail than you’re used to giving. A lot of it might be hard and painful, but you’ve got to agree to answer everything. It’s a leap of faith. I like to climb into the person’s head.”

All proceeds would be split 50-50, and D’Orso’s insisted his name appear on the cover after “and” or “with.” Predictably, there were sparks. Redford balked at revealing that her paternal grandfather was white, and that she had never married the father of her daughter. D’Orso insisted that both facts be in the book, arguing that readers would embrace Redford for her candor. He won the argument, and his prediction came true. “One of Dorothy’s friends said the book sounded so much like her that she thought it was transcribed,” D’Orso says. “I couldn’t receive a higher compliment.”

In addition to taping hours of interviews in order to absorb the rhythms of his subject’s voice, D’Orso interviews friends, families and enemies, visits important locales, and researches personal papers and printed records. He is, at heart, still an old-school reporter, a believer in atmosphere and context and the telling detail. While collaborating with Congressman John Lewis, for example, they drove together to many of the battlefields of the civil rights movement, including Nashville, Birmingham, Selma and the Montgomery bus station where Lewis got his head split open by a ravening mob of white racists.

When a collaboration with the partially paralyzed NFL football player Dennis Byrd won a $1.1 million advance at auction in 1992, D’Orso was finally able to give up newspapering and write books full-time. Over the years he has turned down several potential subjects, including former L.A. police chief Daryl Gates (“a cowboy run amok”), Vice President Dan Quayle (“an idiot”) and P. Diddy (“that asshole”). There have also been disappointments, most notably U.S. Senator Joseph Lieberman’s memoir, In Praise of Public Life. “That’s the one book I’d like to erase off my resume,” D’Orso says. “On paper it looked like a good story, but it turned out there wasn’t any there there. I couldn’t penetrate his facade, and the book was bloodless, lifeless.”

When a collaboration with the partially paralyzed NFL football player Dennis Byrd won a $1.1 million advance at auction in 1992, D’Orso was finally able to give up newspapering and write books full-time. Over the years he has turned down several potential subjects, including former L.A. police chief Daryl Gates (“a cowboy run amok”), Vice President Dan Quayle (“an idiot”) and P. Diddy (“that asshole”). There have also been disappointments, most notably U.S. Senator Joseph Lieberman’s memoir, In Praise of Public Life. “That’s the one book I’d like to erase off my resume,” D’Orso says. “On paper it looked like a good story, but it turned out there wasn’t any there there. I couldn’t penetrate his facade, and the book was bloodless, lifeless.”

And then there was the case of troubled football star Ricky Williams. D’Orso’s immersion in that project included helping deliver Williams’s daughter on the kitchen floor in his Toronto home, and compiling 1,000 pages of transcribed interviews. But three years into the project Williams suddenly made himself invisible until D’Orso, with 300 polished manuscript pages on his desk, swallowed hard and withdrew from the project. Many writers operating on a thin margin would have been devastated by so much wasted effort. D’Orso could afford to shrug it off and move on.

In fact, that’s what money is to him: the freedom to pick and choose his projects, and occasionally fail. “I never had the goal of being rich,” he says, “and I have never been super-ambitious. A newspaper’s big enough for me. As long as I was able to make a living from my writing, I was happy. My ambition was to have people consider my writing truly great. Look, I need to be writing because you can’t be more alive than when you’re climbing into other lives in other worlds, whether it’s the Galapagos Islands or the Arctic circle. I’ve felt rich from the beginning – from the day I split the $40,000 advance for my first book.”

Then again, he felt hire-an-accountant rich on the day he drove to the bank in his wheezing Mitsubishi to deposit his first royalty check from Body For Life, his collaboration with the fitness guru Bill Phillips that became a #1 best-seller. When the bank teller realized the check was for $1.2 million, she looked up at D’Orso, her eyes as shiny as new dimes, and asked: “Are you married?”

Then again, he felt hire-an-accountant rich on the day he drove to the bank in his wheezing Mitsubishi to deposit his first royalty check from Body For Life, his collaboration with the fitness guru Bill Phillips that became a #1 best-seller. When the bank teller realized the check was for $1.2 million, she looked up at D’Orso, her eyes as shiny as new dimes, and asked: “Are you married?”

Most writers – ghosts, collaborators, midwives, brand names, wannabes, novelists, journalists, geniuses and hacks – would kill for the chance to cash such a check and get asked such a question. Michael D’Orso knows this. It’s one of many reasons why he’s a happy ghost.

Image: Pexels/Min.