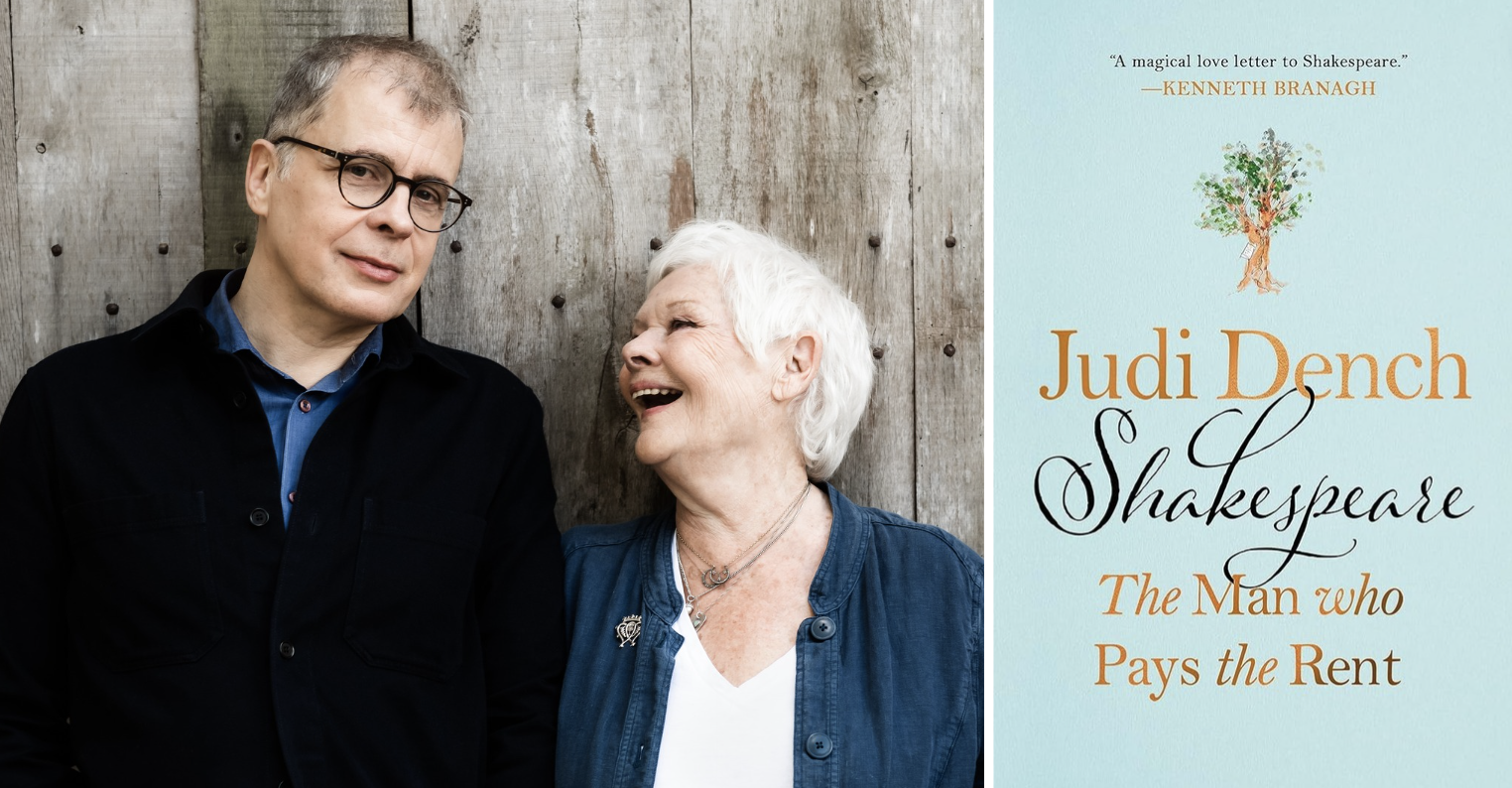

In their candid, comprehensive book Shakespeare: The Man Who Pays the Rent, legendary actress Dame Judi Dench and actor and director Brendan O’Hea discuss Dench’s experiences performing iconic Shakespearean roles, including Cleopatra, Titania, and Lady Macbeth. I talked with Dench and O’Hea about actor-audience reciprocity, the communal experience of theater, and the importance of instinct.

Lenny Picker: How did this book happen?

Judi Dench: I had no conception of making a book; it was Brendan’s idea, after Covid, when we were all completely locked up, and got very bored with ourselves, and Brendan had suggested coming down and just talking about every role I played. I’d never done that before. I’ve talked about individual plays, but I’ve never spent hours, just discussing and remembering things. It was actually a rather cleansing experience for me, and something I never thought I would get the chance to do. It amazed me how many plays I’d actually done. And it brought back a great amount of memories because Brendan had done his homework very successfully.

LP: Brendan, is there something that you learned from talking with Judi that shaped how you directed Shakespeare?

Brendan O’Hea: After interviewing Jude about A Midsummer Night’s Dream, I directed it at the Globe Theater. The breakthrough for me in doing so was Jude saying that Titania is completely besotted with Bottom, and it was the truthfulness of that, that was, for me, kind of revelatory, because it really released the comedy. As Jude says in the book, an actor playing Bottom can camp it up and muck about, but Titania has to be totally in love with him, and that’s where the charm and where the humor comes from.

LP: Judi, what was your very first Shakespearean role?

JD: My first job was at the Old Vic in 1957, and I got very dodgy notices indeed when I played Ophelia. Michael Benthall took an enormous chance on casting me just out of drama school. It was right that I should get dodgy notices, because I didn’t know the business properly. But Michael, I owe such a lot to him because he said, stay with the company, and you’ll play small parts, you’ll understudy, you’ll play everything. I remember never going to my dressing room at the Vic. I remember standing only on the stage and watching other actors all the time.

LP: Do you have a favorite of the parts you played in a Shakespeare play?

JD: People used to laugh openly when they heard I was going to play Cleopatra because Cleopatra is a very tall, beautiful Egyptian woman, and I am just barely five feet, and a very British person. I just loved it and Tony Hopkins was heaven playing Antony; there’s one long scene, and I remember Peter Hall directed it by saying, “I’m not going to set the scene, I’ll leave it to the two of you.” And so there was an incredible danger about it, but the adrenaline it made was phenomenal. And some of her speeches are just wonderful—well, like all of them.

LP: You also played Lady Macbeth; how do you understand her?

JD: I’ve never urged anyone to murder somebody, but when I played Lady Macbeth, I had to find the reason for her to do it. It’s out of love for him that she does it. You hear very early on in the play that they’re so mad about each other that she wants everything she wants. And she says, by God, he’s gonna get it too. He’s gonna have exactly what he wants. And if it means that we have to do away with the king, we’ll do away with the king. It is interesting that her first lines are about the fact that he is a mild-mannered man—that although he may want what the witches prophesied, he may not have the guts to go through with it. But she says, by God, he’s going to, I’m going to see he does.

LP: In the book you talk about doing a lot of homework preparing for a role, trying to figure out the character’s inner life and backstory; to what extent did you study scholarship to do so?

JD: I’d never studied a great deal of Shakespeare at school. My older brother Jeffery (1928-2014) was an actor, and still holds the record of appearing in more seasons with the Royal Shakespeare Company in Stratford-upon-Avon than anyone else, and through him, I was brought up with it very much. I would say that I was entirely instinctive; you can do a scene in a play with one actor, and then you can do the same scene with another actor, and something else will come out of that. So I believe very much it’s an amalgam of a coming together of what you, and what you bring out of an another actor—that might make something that everybody knows very well quite unique in a certain way.

LP: Brendan, does that approach resonate with you?

B O’H: Yes—I think maybe I had a tendency as an actor to overcomplicate things,

and maybe before working on this book with Jude, probably as a director, I tended to overcomplicate things. But Jude is very good at the instinct—to just get into the simplicity and the truth of it, and also just telling the story as it happens. As she said from her work with Sir Peter Hall, “you can’t play the whole of Cleopatra in the first scene.” It’s like a mosaic. You play one aspect of her, then the next scene, you play another aspect. And by the end—this is Jude’s analogy—it’s like a Seurat painting, where you’ve got a dot of red, a dot of blue, a couple of dots of green, and you stand back and there’s a woman with a parasol. I think that’s a wonderful analogy for acting. You don’t have to overload every single scene with the whole character. You just play aspects. So that insight from Judi was a revelation for me as well.

LP: Judi, could you expand on your comments in the book about the importance of your audience to your performances?

JD: I think that that’s why every single performance you do for an audience is different. What is so wonderful is that after you have been doing a play, you can have been doing it for weeks, and suddenly you come to a night where you feel for some reason that the audience brings out something else in the play and somehow that is very contagious to actors. Acting is the art of reacting—obviously that’s to do with what you do with your fellow actors, but that’s as much to do with the audience as well. It’s a communal experience—they will bring something and you bounce off them. You can’t just go from A to B and then go home. We are only as good as the audience and the audience are only as good as us. It’s a reciprocal contract that we have. And that doesn’t always happen, but when it does, it’s electric, isn’t it?

LP: Is there a specific example that comes to mind,?

JD: When I played Cleopatra, I knew that there was one line that she said that should have a laugh—I knew that it was said to get a laugh. We did 100 performances of Antony and Cleopatra at the National and on the hundredth, I got the laugh. Now, I don’t know why—perhaps I finally said it in the right way.