Maria Bamford doesn’t worry about being noticed at the dog park. “It’s Los Angeles,” she tells me over the phone when I ask if anyone recognizes her from her decades-long comedy career. “Nobody gives a shit if they did.” When she offers to text me a photo of her dogs patronizing said park, I decline for the sake of maintaining a professional facade.

I’m a fan of Bamford’s, from her semi-autobiographical Netflix series Lady Dynamite to her Portlandia-esque Target commercials. We’re having our first of two calls to discuss her debut book, a tongue-in-cheek riff on self-help and For Dummies called Sure, I’ll Join Your Cult. The book delivers the precisely unsettling intimacy that Bamford’s stand-up comedy is known for when it comes to chronic loneliness, disturbing thoughts, and an unfortunately relatable apathy toward living.

“I’m not suicidal,” Bamford prefaces in the book’s introduction. “But I’m also not particularly psyched.”

Bamford brings this dead-pan sincerity to the story of her life, including topics even career memoirists sidestep: unwanted violent thoughts, in-patient psychiatric treatment, and how much money she and her husband have in assets. (She even invites readers to email her with feedback about her charitable donations.)

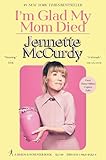

Bamford’s humor is smart and sad, sincere and self-deprecating; she’s been called a comedian’s comedian, but by the time I finished reading her book, I mentally recategorized her as a weirdo’s weirdo. She’s also an expert in her own lived experience, and and this hilarious, aching book manages to feel in conversation with literary works like The Collected Schizophrenias by Esmé Wejun Wang, Sick by Porochista Khakpour, and Ask Me About My Uterus by Abby Norman, as well as Jeanette McCurdy’s I’m Glad My Mom Died, another celebrity memoir celebrated for its similarly brutal and charming honesty.

Bamford’s humor is smart and sad, sincere and self-deprecating; she’s been called a comedian’s comedian, but by the time I finished reading her book, I mentally recategorized her as a weirdo’s weirdo. She’s also an expert in her own lived experience, and and this hilarious, aching book manages to feel in conversation with literary works like The Collected Schizophrenias by Esmé Wejun Wang, Sick by Porochista Khakpour, and Ask Me About My Uterus by Abby Norman, as well as Jeanette McCurdy’s I’m Glad My Mom Died, another celebrity memoir celebrated for its similarly brutal and charming honesty.

I spoke with Bamford about workers rights, making money as an artist, and the intrusive thoughts we both live with over the course of two phone calls in July.

Marissa Higgins: Can you summarize your book in a few sentences?

Maria Bamford: It’s a For Dummies-version of a mental health memoir. Hopefully not too many big words. It’s okay to skip giant swaths and just read the prurient details, which is what I always do with the For Dummies books. Just the saucy bits and then move on.

MH: Your book covers really nuanced material in terms of mental health; specifically, living with some of the less palatable realities of OCD. What would you tell people who don’t understand unwanted intrusive thoughts?

MB: Ask somebody: Hey, have you ever had a weird thought? Like, oh my god, why did I think that? One of those weird, creepy thoughts where you’re like, I don’t know where that came from? Most people just go, Oh, that was weird—anyway! And go on with their day. Somebody who has a special brain goes: Oh, that really means something about me. Then suddenly it becomes an obsession, and then you gotta do a compulsion to get it away.

MH: What are the biggest misconceptions about seeking mental health care in the US?

MB: I think everybody has got a health care experience to talk about. It’s just not ideal in our country unless you have the money where it’s a concierge service. And even then that’s problematic; I got my current psychiatrist, who basically just refills my prescription any time I want, which is a little bizarre. So I think I’m gonna change to a psychiatric nurse.

I’m training to be a peer specialist, which is a new designation under the funding of mental healthcare in California. They hire people to be a part of mental health teams to go out with emergencies or drop-in centers. The isolation of seeking care starts with saying, Okay, if something’s wrong, you’ve got to go someplace special… that won’t let you in. When you’re hospitalized in a “good facility,” that can be traumatizing, too, especially if you have a dual diagnosis and a number of things going on. I think what gives me hope is the ground floor of family and community care.

MH: You interrogate your privileges in this book. Why is this important for you to address on the page?

MB: I work in show business; it’s kind of par for the course to say you’re mental. I’m having a luxury love boat experience. The person who’s most interesting to ask is somebody who’s trying to have a job, trying to find housing, trying to maintain relationships and family. That is so much more interesting. I hope the voices of people—the majority of people—living without any of these privileges are amplified.

MH: You’ve talked about mental health in your shows for a long time. Have you always had a thick skin?

MB: No. I still don’t have a thick skin about it. I feel terrible if somebody tells me I’m a monster or I’m a bitch or I’m crazy or whatever. Oh my god I feel horrible. I do not look at my Youtube comments. I definitely only look at the five star reviews on my audiobook. I’m living in a bubble of pink, pink light.

MH: Did you get feedback earlier in your career or have you always worked in isolation?

MB: Totally in isolation. The person whose opinion matters the most is myself, you know? That’s the reason I did stand up—I got to make the decisions. As a child, I felt powerlessness and like I couldn’t choose things. I do get feedback, and I do appreciate that, especially when somebody’s trying to educate me. That’s awesome. But as far as checking with somebody, Hey, is this funny? That hasn’t been interesting to me.

MH: How does the book fit into your body of work? Does it feel like part of your comedy career?

MB: Totally. I did reuse and recycle anything I’ve done in my act—it’s a little depressing when you go, Wait a minute, I’ve heard her say this on stage! I wanted unique content. The only thing that was really different is writing without an audience. Writing without performance was very uncomfortable and a little scary for me in terms of wanting to sound smart. It’s unfortunate, some sort of pride thing, where I’ve read gorgeous memoirs regarding mental health, and I think, Oh, this is gonna be slop comparatively, but that’s okay. We need slop.

MH: What books did you read while working on the book?

MB: Gorgeous mental health memoirs, and so many writer biographies, especially about dead alcoholic poets. Red Comet: The Short Life and Blazing Art of Sylvia Plath by Heather Clark; extremely depressing poet biographies from the fifties and sixties. My favorite!

MB: Gorgeous mental health memoirs, and so many writer biographies, especially about dead alcoholic poets. Red Comet: The Short Life and Blazing Art of Sylvia Plath by Heather Clark; extremely depressing poet biographies from the fifties and sixties. My favorite!

MH: What was your editing process like?

MB: Some things were like, Could you add a few lines to be more clear? And then extensive typos.

MH: How do you know when a joke is done?

MB: I think you just stop working on it. It seems good, and then sometimes it changes, and then, then, then usually, I really wanna let it go. I just recorded an hour of material and now I’d like to change out all my material. But that will be a slow process.

MH: What’s your recording process like?

MB: I slowly start adding new things to the old hour and then hopefully it’ll slop over into a new hour. I don’t have any structured way of doing it. I just think, It’s happening! I’ve used a performance space near my house, a little tiny theater on like, noon on a Saturday. I’ll run 45 new minutes. When I go on the road, I try to just add a few new bits to each show.

MH: How do you structure a show?

MB: I don’t do a whole new hour; I feel too self-conscious. I also feel like, Oh, people deserve to have a well-thought out show. I mean, I don’t know if there’s that much difference between a well thought out show and one that hasn’t been, but in my mind, there is! The changes probably take a year or so. It takes a long time, but I’m not in any hurry.

MH: How did you know when your book was done?

MB: The people I was emailing from Simon & Schuster said OK and seemed to accept it as being done. They said we’re gonna start editing it now, and I was like, Oh, okay. So then I guess it’s done?

MH: Do you want to write another book?

MB: Someone needs to offer me money! I think I would. I always like to write from excitement. And I do enjoy being paid. But I was also excited about writing a book because I’ve never done such a thing. So I thought, Oh, this will be an interesting process. I’m grateful I was given this opportunity, and it’s okay if it ends here. I have a book club I belong to and I can just enjoy the work of others.

MH: Maria! Is your book club going to read your book?

MB: I hope not!

MH: Last question—what would you tell your younger self?

MB: Your mind will be blown. Maybe spend more time with friends and family rather than focusing on work. Relax and hang out more. I was so socially anxious, I didn’t really do that. The weird thing about writing some sort of memoir before your life is over is like, Oh no! Well, other stuff is gonna happen now. You get scared! I should read my birth chart, see what’s coming up.