This was the sixth phone call I’d made. My question was always the same. Have you heard of someone called R. D. Twala, who ran as a candidate in the 1963 legislative elections in Eswatini, a country in Southern Africa? Twala had lived in the small town of Kwaluseni, on the outskirts of Eswatini’s second-largest city, Manzini. Whoever this person was, Twala was also an accomplished anthropologist whose work was published in the prestigious journal African Studies (in which no biographical detail accompanied its articles). I had also come across R. D. Twala in the Uppsala University archives of the Swedish historian Bengt Sundkler. Twala had worked as a researcher for Sundkler in the late 1950s, sending the Swedish scholar meticulously crafted reports on religion in Eswatini. Whoever they were, woman or man, R. D. Twala was intelligent, erudite, politically active, and highly opinionated. My curiosity was piqued. I wanted to learn more about them.

But the answer to my question was also always the same. The historians whom I asked (both professional and lay), the journalists, the political activists, and the Kwaluseni residents all hesitated, thought for a few seconds, and then—I could sense it on phone calls—shook their heads and gave me a no. R. D. Twala was someone about whom they knew nothing at all. The name didn’t even elicit a stirring of vague recognition. A complete blank. I was surprised. I had expected that a candidate in Eswatini’s first semi-democratic elections—a momentous occasion for the country, just five years before it gained independence from Britain in 1968—and an individual who was a rare published Black African anthropologist of the 1950s would have left some imprint in public memory. Eswatini, moreover, was not a large country—only seven thousand square miles, slightly smaller than the state of New Jersey. My experience of growing up in Eswatini in the 1980s and 1990s was that this was a country where it was hard to remain anonymous.

My sixth phone call broke my streak of bad luck. I was contacting Professor Bongile Putsoa, an academic in her eighties who had taught at the country’s university for many years (the university was in the small town of Kwaluseni, adjacent to busy Manzini). I rang Putsoa and gave my usual explanation. But before I had finished, Putsoa laughed and cut me off: “Oh, you must mean Regina!” For the next fifteen minutes, Putsoa spoke about a woman called Regina Twala who had lived in Kwaluseni in the 1950s and 1960s and who had died in 1968. (I later found out that Regina was born in 1908, placing her at an early sixty when she died.) Putsoa had been a young woman in the 1960s, and her memories of Regina energetically striding around Kwaluseni were still vivid. In Putsoa’s recollection, Regina was a social worker engaged in uplift of the community, although she did also hazily recall that Regina was active in politics. One thing in particular stood out in Putsoa’s memory. Regina had founded a small library, certainly the only one in Kwaluseni and one of only a very few in the entire country in the 1960s. The tiny building still stood today, Putsoa told me, although now a broken shell with a tree fallen through its roof. She would take me to see it.

I met with Putsoa a few days later, and she did indeed take me to see the old library founded by Regina Twala. It was now a sad ruin under the Kwaluseni sun. A fading name in peeling paint read “Prince Mfanyana Memorial Library.” Regina had named the library after Abner Mfanyana Dlamini, the first liSwati man to gain a university degree. Inside I could still see ancient, overturned bookshelves. I would later learn that Regina’s founding of this library spoke to her lifelong dedication to the emancipation of the emaSwati people from British colonial rule and to her conviction that education was integral to this goal.

Obscurity and marginalization (frequently at the hands of white scholars) are themes that shape Regina Twala’s life and legacy. Bringing marginalized people into focus is not a unique predicament for a biographer. There is an entire genre of biography that tells the little-known stories of ordinary women and men, deliberately eschewing attention to the elite, the famed, and the celebrated. Many of these biographies focus on quotidian figures as a way of illuminating a particular period or region. Biographers select “ordinary” people not for their extraordinary features but rather for their everyman qualities. But Regina Twala does not fit this pattern of an obscure woman being clawed from the blank forgetfulness of the past by a dedicated historian. As I was fast finding out, she was far from an ordinary woman. Regina was part of a tiny group of middle-class professional Black women of twentieth-century Southern Africa. In her company were the first female nurses, doctors, teachers, politicians, and social workers, pioneering figures who pushed the boundaries of what was considered acceptable feminine behavior. Yet even among this illustrious company, Regina stands out as exceptional.

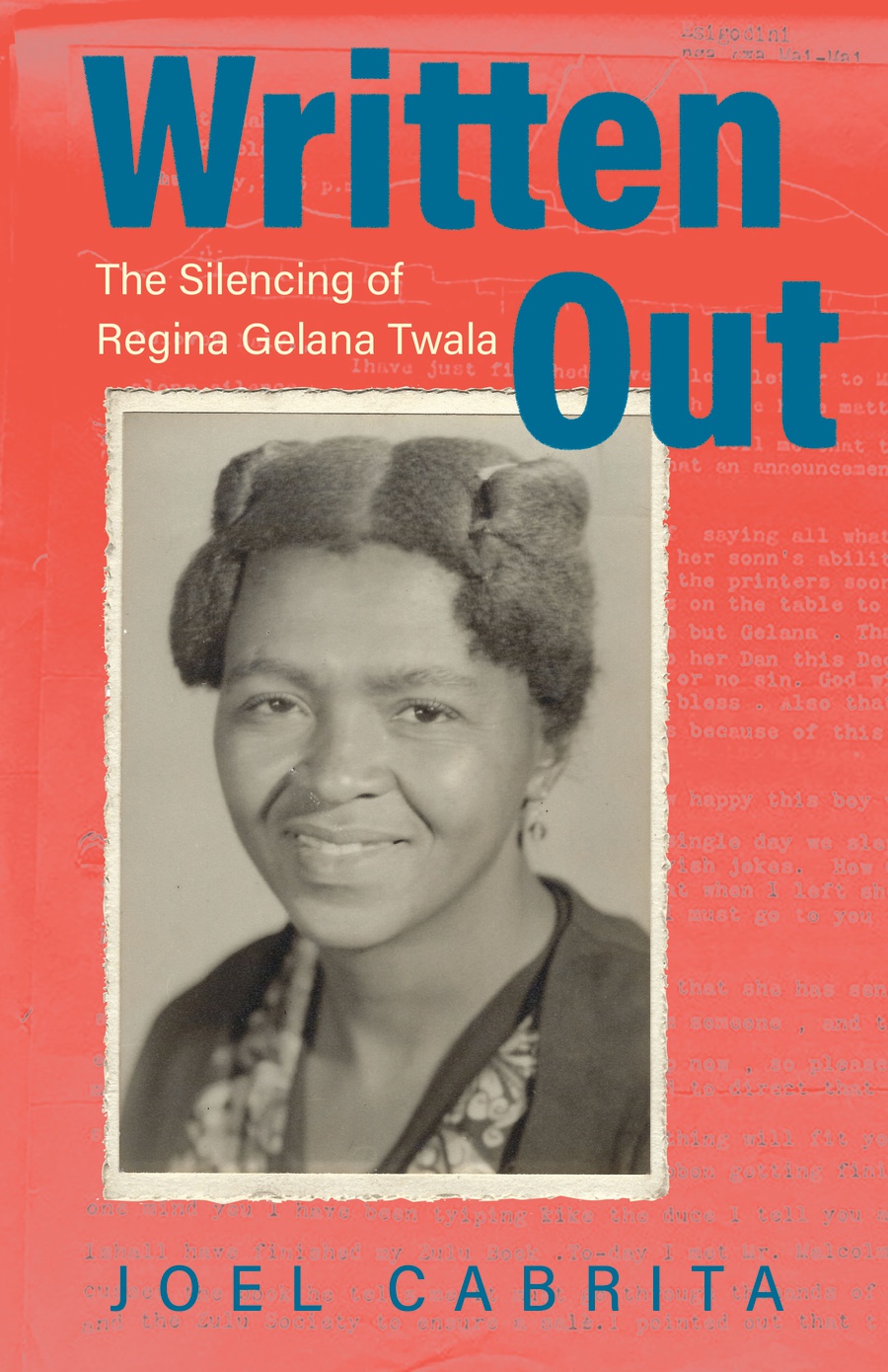

Born and raised in a Zulu family in the small village of eNdaleni in the Midlands of South Africa, Regina Twala would be only the second Black woman to graduate from the prestigious University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, emerging with a degree in social studies (a mixture of sociology and anthropology). Throughout Regina’s life, she wrote prolifically, producing perhaps as many as six book manuscripts (only two survived, one only partially) and over one hundred journalistic and academic articles. Alongside her academic interests, Regina was also an active political figure, protesting for many decades against the racism of the South African apartheid state and against the British colonial state in neighboring Eswatini. Regina also emerged as an outspoken critic of the traditional Swati monarch, Sobhuza II, who seized absolute power after the departure of the British.

Regina’s personal life was just as extraordinary. Those who knew Regina remember her as stubborn, opinionated, passionate, determined, and difficult. She could be kind to those in need and bitingly dismissive of those in power. Briefly married and subsequently divorced in the mid-1930s, Regina braved societal censure against women who left their husbands. She chose the prospect of a better life against the known reliability of an unhappy marriage. Regina’s second marriage to the prominent Dan Twala—a thirty-year-long relationship—was a rich and multilayered intellectual, emotional, and physical union, marking the pair out as one of the power couples of midcentury Southern Africa. Yet this was the woman whom history seemed to have forgotten. What was I to make of this puzzle? How was it that a woman as talented, unusual, memorable, and prolific as Regina Twala had been so thoroughly erased? She was a political leader in an era where few women occupied leadership roles, an intellectual luminary, an author of multiple works, an outspoken journalist, a university-trained anthropologist, and an unconventional defier of norms for women. Regina was certainly not an “ordinary” woman, not by the standards of the 1950s and not even by criteria of the 2020s. Regina, rather, was a blazing star, someone who pioneered numerous firsts for Black women in two different countries in Southern Africa. That a woman did nothing “exceptional” of course does not make her life any less worthy of remembering. But taking into account Regina’s many accomplishments does make her invisibility to contemporary audiences all the more puzzling.

Yet the erasure of Regina Twala is a predicament shared by very many African women of the twentieth century. Generations of accomplished female professionals—writers, artists, doctors, and politicians—are virtually unknown outside of their immediate families. One way to measure what writer Zukiswa Wanner calls Black women’s “constant flirtation with erasure” is these women’s difficulty in gaining the attention of biographers. While biographical coverage of African men is regionally uneven (South Africa predominates, while other parts of the continent are relatively unrepresented; the last biography of a liSwati individual was published in 1981), biographies of African women from anywhere in the continent are still a vanishingly rare species. Of the 225 biographies published of South African figures since 1990, I count only ten that have focused on women.

One might argue that African women’s biographies remain unwritten because there is simply not enough material with which to construct their lives; sexist societies have undoubtedly marginalized women from written official records. But the biographers of a nineteenth-century South African Khoikhoi woman, Sara Baartman, still managed to write her story despite a nearly complete lack of written documents for a biographical subject who had died two hundred years ago. And historian Athambile Masola reminds us that the chroniclers of African women should search for their stories in locations that are far from obvious. Often women’s lives appear in the footnotes of written records more concerned with documenting the deeds of men. Scarcity of materials, moreover, was clearly not an issue for Regina Twala. This is not a woman whose written output has disappeared or that did not exist in the first place. Moreover, Regina’s prominence in social and political life—her university education, her high-profile political activity, her social work—all meant that her activities were frequently covered in newspapers in both South Africa and Eswatini. Indeed, it is rare to write about a Black South African woman who has left behind quite so much trace of her life, both archival and published. How, then, are we to explain the silence about her, given there is simply so much material for a curious biographer to get on with?

Given Regina Twala’s bitter experience with white scholars, my own role as biographer is an uncomfortable one to occupy. If Regina is a woman written out of history—both in her own lifetime and afterward—what does it mean that her reintroduction to history is being mediated through myself, a white academic? I am a professional historian residing in North America and employed by a prestigious university. I am, moreover, of white Southern African ancestry: my parents—one an Afrikaner, the other a joint national of Portugal and Mozambique—moved to Eswatini in 1982 when I was two. I lived there until 1998 and on and off since then. My bringing Regina’s work to light is thus shot through with inherited issues of race and privilege. My family’s and my story are part of the history of white supremacy in Southern Africa.

So, however important it is that Regina’s story is finally coming to light, that it takes the mediation of a white academic from the Northern Hemisphere to do its telling would surely have rankled Regina. For all her desires to publish her corpus, manage the narrative of her life, and consolidate her legacy, the task of telling her story and of bringing her work to public attention has been taken up by another—and, what’s more, by an academic employed by the kind of well-funded institution at which Regina was never able to find work. These are dynamics intensely familiar to African studies as a whole, a field of study historically dominated by white scholars (many in the northern hemisphere) telling the stories of Black African individual and communities. When viewed in this light, it is hard to view my biography of Regina in a straightforwardly rehabilitative sense, to laud it as a worthwhile restoration to memory of an important lost figure. Instead, my biography begs difficult questions about continued white privilege in telling the stories of Black historical subjects and of the entrenched institutional power of the universities and presses that have supported my career while spurning individuals like Regina Twala.

Telling the story of a written-out woman thus leads us straight to the crucial question of agency. Since the 1980s, as part of the broader shift toward “history from below,” scholars have celebrated historical actors’ possession of agency and the fact that even the most oppressed individuals are able to assert autonomy and self-determination. Yet, as the literary scholar Naminate Diabate powerfully claims, “There is no agency outside of restrictions.” We might also think of the words of anthropologist Talal Asad: “No one is ever entirely the author of her life.”

Written Out: The Silencing of Regina Gelana Twala by Joel Cabrita, (Athens: Ohio University Press, Copyright © 2023). Reprinted with the permission of Ohio University Press and Wits University Press.