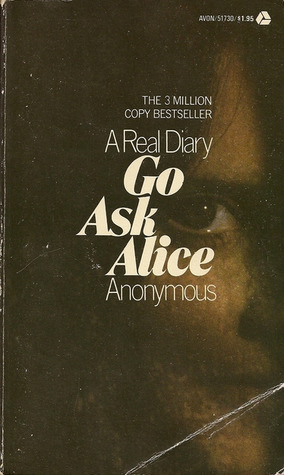

I don’t know how I came by my copy of Go Ask Alice. In my memory, the book appeared on my bedroom bookshelf one day, a small mass market edition with yellowed newsprint pages and a glossy black cover that made it seem slightly illicit. Like other talismans acquired during my teenaged years, its provenance felt mysterious, like the punk mix-tape I found on the floor of my car, or the cardigan that might once have belonged to a friend’s friend but now hung in my closet. Then again, I might have bought my copy from the Kramer Books in D.C.’s Dupont Circle and just forgot.

For those who haven’t read it, Go Ask Alice, attributed to “Anonymous,” narrates a series of increasingly calamitous drug trips taken by a 15-year-old diarist, who is inducted into this doomed timeline when someone at a party laces her Coca-Cola with LSD. (To this day, when I see a solo cup, I think, “Button Button, Who’s Got the Button”). After the fated soda, our heroine’s descent is swift. She experiments rapidly and in seemingly random order with a range of opiates, hallucinogens, uppers, and downers; takes a bus to San Francisco; falls into sex work; and only then turns to that most dangerous of controlled substances—weed.

At 14, I was hardly worldly, but even I knew there was something fishy about this sequence of events, which reversed the reefer-madness-era rhetoric of pot as gateway drug. “They don’t call it dope for nothing!” my best friend’s mother liked to remind us, often while tipsy on Chardonnay. It seemed even more absurd that a supposedly strung-out teen would have the presence of mind and writing materials on hand to maintain an up-to-date diary. “Like here I am in Denver,” begins one of several entries that a footnote informs us were found scrawled “on single sheets of paper, paper bags, etc,” and retrieved at an indeterminate date by some angel collator.

So why did I find myself coming back to this clearly fake “found” manuscript? One which, I discovered later, was actually penned by a middle-aged Mormon therapist and youth counselor named Beatrice Sparks, who developed a sideline forging diaries by wayward teens, and whose next effort chronicled the downfall of a young Satan worshipper?

On the one hand this dispatch, however phony, offered access to an actual rather than ersatz counterculture—that is, it belonged to a moment when there was a counterculture of sufficient potency to be perceived as a threat. This, by contrast, was the ‘90s, the era of Woodstock ‘99, a sad retread of the original festival, featuring Korn and Limp Bizkit, and faux-vintage army jackets from Urban Outfitters. We had Riot Grrrls and grunge but neither had political teeth; feminism’s third wave was a pale version of its second. To paraphrase Portlandia, the dream of the sixties was alive in this bizarre piece of 1971 propaganda, even if—or, really, because—it imagined the decade as a nightmare.

But the appeal was about more than nostalgia. I was fascinated by the book’s obviously suspect moral agenda. A child of the Reaganite ‘80s, I grew up with after-school specials, D.A.R.E. campaigns, and commercials that likened my young brain on drugs to an egg sizzling in a hot pan. I knew fear-mongering when I saw it, but I also came of age believing Reading Was Fundamental, and so to my mind books existed in some space apart, free from politics or adult interference.

Go Ask Alice, in short, was my crash course in ideology—the text that taught me texts are never neutral. Paradoxically, it took encountering this exercise in obfuscation to raise my consciousness. It’s not too much to say that the book helped me learn how to read: skeptically. That I am now a person who teaches students to think and write critically about narrative is not directly due to this book, of course, but it’s not entirely unrelated.

Many years later, during a John Carpenter kick, I watched his 1987 film They Live. In a famous sequence, the protagonist puts on a pair of sunglasses that allow him to literally see the messaging implicit in mass media: “Obey!” “Marry and reproduce!” “Consume!” Go Ask Alice might as well have come emblazoned with its own axioms: “Don’t do drugs!” “Stay in school!” “Avoid parties!” And even more pointedly, “Hippies are bad!” “Sex is bad!” “White femininity is always endangered!”

Really endangered, it turns out, since—spoiler alert—we learn in the final pages that the girl, returned to the bosom of her family but having suffered a bad trip, has died. “Was it an accidental overdose? A premeditated overdose? No one knows, and in some ways that question isn’t important,” an editorial presence concludes solemnly, in an obviously tacked-on coda. “What must be of concern is that she died, and that she was only one of thousands of drug deaths that year.”

In an era of shrill extremism, this sober polemicizing feels almost quaint. Sure, the messaging is clumsy; yes, the book reads like one long PSA. But such ostentation has its purpose: it gives you practice recognizing bad ideas. Most efforts at secular indoctrination aren’t this obvious. Most authors don’t broadcast their bias so clearly that it occurs to young readers there might be something to resist.