In his 1975 novel The Monkey Wrench Gang, Edward Abbey famously based the character of George Washington Hayduke, a Vietnam veteran turned ecoterrorist, on the real-life environmentalist Doug Peacock. Hayduke was a hero for increasingly excessive and exploitative times. Peacock’s own entry in the canon of environmental literature, the 1996 book Grizzly Years: In Search of the American Wilderness, was an earnest if rather quiet paean to living more respectfully, even reverently, in relation to animals and the planet. Since then, the environmental movement has spiraled out of the wilderness and finds itself far beyond Abbey’s and Peacock’s American West—it matters everywhere, in all regions and at all levels. So what is the role of such traditional environmental literature these days?

In his 1975 novel The Monkey Wrench Gang, Edward Abbey famously based the character of George Washington Hayduke, a Vietnam veteran turned ecoterrorist, on the real-life environmentalist Doug Peacock. Hayduke was a hero for increasingly excessive and exploitative times. Peacock’s own entry in the canon of environmental literature, the 1996 book Grizzly Years: In Search of the American Wilderness, was an earnest if rather quiet paean to living more respectfully, even reverently, in relation to animals and the planet. Since then, the environmental movement has spiraled out of the wilderness and finds itself far beyond Abbey’s and Peacock’s American West—it matters everywhere, in all regions and at all levels. So what is the role of such traditional environmental literature these days?

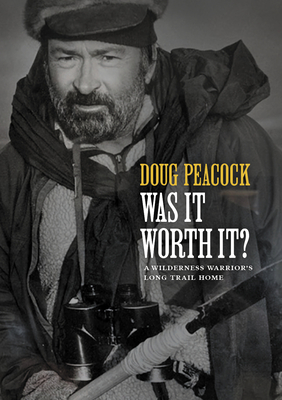

Reading jacket copy of Peacock’s latest book, Was It Worth It?: A Wilderness Warrior’s Long Trail Home, one might expect more of the same. But Peacock is hardly at war in this book—there is no monkeywrenching, no dramatic tales of brute survival. The single threat of close combat comes when Peacock fabricates an eight-foot spear just in case a polar bear charges him during an expedition in the far north—an incident that he really, really hopes will not happen. (Spoiler: It doesn’t.)

Was It Worth It? is a collection of essays culled from across the past few decades, all of which reflect Peacock’s decidedly subdued approach to wilderness adventuring, and writing. Indeed, whereas the jacket describes the book as “gripping stories of adventure,” readers might be delighted to find instead a recurrent lack of adventure on the page—at least, by expected standards. If the narratives “grip,” it’s because of Peacock’s prose: the adventure lies in the wording, a suspense built by sentences. Apex predators and sublime wilderness remain curiously—and importantly—elusive throughout the book. The “long trail,” such as it is, is meandering, often mundane, and with plenty of dead ends.

It’s an understandable marketing move by the book’s publisher, Patagonia, to play up Peacock’s mythos. But a very different story begins to emerge within the pages—I found myself surprisingly moved and inspired by Peacock’s mellow, methodical, and meditative recounting of various trips and landscapes. Was It Worth It? is about his friendships with people and encounters with wildlife, and about some solitary experiences too. Simple if simply decadent meals are cooked over campfires; beers are consumed, and sometimes poured out rather than imbibed, to honor past lives.

Peacock is a masterful observer of detail, wherever he is. In many ways the book is a paragon of nature writing. But the detailed accounts often subvert the genre. For instance, on a solo trip down the Jefferson River in Montana, he writes about the many diversion dams that channel and attempt to control the river’s current. These “little dams” are both a physical obstacle to his journey, and a semaphore of the type of human intervention that Peacock often rails against. But he doesn’t blow them up or damn them to hell; he just navigates his old wooden drift boat around them, at times with great effort, on his way down the river. Early in the trip he admits that he’s not even sure how many of these dams there are on his route. But: “It didn’t actually matter, as I had no choice but to keep going; I’d figure it out as I moved downstream.” So long wilderness warrior, hello Taoist ordinaire.

On that same river trip, Peacock occasionally stops to fly fish, but these scenes are delightfully anticlimactic. Seeing some big trout rising at the end of a run of rapids, he “felt all the old magic again.” But unlike Hemingway’s Nick Adams, who feels something similar, the fish don’t bite for Peacock. After the initial anticipation and a few excited casts, the scene fizzles entirely: “Nothing doing.” Peacock quits fishing as abruptly as the trout first appear in all their alluring splendor. Again the book upends the genre conventions, spending more time in a quiet, ruminative state rather than relishing in ornate imagery and dramatic escapades. (Another story includes a slightly more successful fishing interlude, on Belize salt flats, but even it features photo of the fly fisherman above a self-deprecating caption: “Doug fishes poorly; skunked again.”)

On that same river trip, Peacock occasionally stops to fly fish, but these scenes are delightfully anticlimactic. Seeing some big trout rising at the end of a run of rapids, he “felt all the old magic again.” But unlike Hemingway’s Nick Adams, who feels something similar, the fish don’t bite for Peacock. After the initial anticipation and a few excited casts, the scene fizzles entirely: “Nothing doing.” Peacock quits fishing as abruptly as the trout first appear in all their alluring splendor. Again the book upends the genre conventions, spending more time in a quiet, ruminative state rather than relishing in ornate imagery and dramatic escapades. (Another story includes a slightly more successful fishing interlude, on Belize salt flats, but even it features photo of the fly fisherman above a self-deprecating caption: “Doug fishes poorly; skunked again.”)

Some of the stories told in Was It Worth It? are legendary, such as Edward Abbey’s secret desert burial and the wake that followed. But Peacock tells these stories in plain language and with simple aplomb, the effect being that the mythical figures of the environmental literary canon are brought down to earth—right where they should be. In this way Peacock is paving the way for all sorts of writing and art that is indebted to, but grown up and out of, the earlier phases of green activism. The point isn’t to keep repeating the slogans or elevating the masters: now, we need to make it real, and keep it relevant. After a certain bear sighting in British Columbia, Peacock articulates the outcome of the experience with utter directness and precision: “The presence of this vulnerable animal shattered my anthropomorphic prejudices.” Rather than being outdated or obsolete, we need this kind of ecological humility more than ever—at this moment when, as Peacock remarks in another chapter, “the hot winds of climate change are coming for us all.”

Beyond Peacock’s sober reflections on climate change and imminent ecological destruction, there are at least two other sources of trauma haunting this book. There is Peacock’s own acknowledged PTSD from his time in Vietnam; this comes up several times throughout the book, almost repetitively—just as flashbacks would for someone suffering from the disorder. Then there’s Peacock’s keen awareness of the erasure of indigenous peoples and cultures, and the ancestral role he plays in this ongoing arc of history. At one point, in another episode that almost reads as absurdist, Peacock and his cousin sneak around suburban lower Michigan to “repatriate” a cache of arrowheads and other ancient tools that Peacock had dug up and collected as a kid. The reader hovers above the page as Peacock commando crawls through a flower garden outside a McMansion, to restore some semblance of cosmic order. It’s a touching scene, absolutely serious and a bit funny, too—which is to say, classic Peacock.

I have been reading—or reading about—Doug Peacock since my college years in the ‘90s, when I first started to study environmental literature. We share a mutual friend in the Montana poet Greg Keeler, and Peacock offered a generous endorsement for my book Searching for the Anthropocene. So I was hardly a neutral reader of this new book. But having taught and written about environmental literature for two decades now, I come at this genre with a sharp critical sense of what works, and what doesn’t. When I first heard about Peacock’s new book, I’ll admit that I thought the title was glib. Was it worth it? Was what worth it? What could that even usefully mean? But reading the book, going along with Peacock on his trips through the mind and across the planet, the question takes on multiple registers. It reverberates, pressing on the reader in a way that is not just useful but urgent. Nature writing is more difficult, and more important, than ever. I had thought about this when reading other recent books that loosely fall in this realm, and are actively expanding it, like Lauret Savoy’s Trace, Helen Macdonald’s Vesper Flights, and Barry Lopez’s last book Horizon—all books that show how the work of observing and deriving lessons from our world gets dragged down by all the weights of human history and our present conundrums.

I have been reading—or reading about—Doug Peacock since my college years in the ‘90s, when I first started to study environmental literature. We share a mutual friend in the Montana poet Greg Keeler, and Peacock offered a generous endorsement for my book Searching for the Anthropocene. So I was hardly a neutral reader of this new book. But having taught and written about environmental literature for two decades now, I come at this genre with a sharp critical sense of what works, and what doesn’t. When I first heard about Peacock’s new book, I’ll admit that I thought the title was glib. Was it worth it? Was what worth it? What could that even usefully mean? But reading the book, going along with Peacock on his trips through the mind and across the planet, the question takes on multiple registers. It reverberates, pressing on the reader in a way that is not just useful but urgent. Nature writing is more difficult, and more important, than ever. I had thought about this when reading other recent books that loosely fall in this realm, and are actively expanding it, like Lauret Savoy’s Trace, Helen Macdonald’s Vesper Flights, and Barry Lopez’s last book Horizon—all books that show how the work of observing and deriving lessons from our world gets dragged down by all the weights of human history and our present conundrums.

Peacock’s new book isn’t prescriptive, and isn’t overtly heroic. It’s realistic, modest, even. But it shows how close humans always are to our biological being, a fact to be ignored at our own peril. Peacock’s essays reveal how it’s always worth it to pay attention—and not just during high-profile adventures. The true adventures of environmental awareness might always be taking place off to the side of where the action seems to be. Or, really, the adventure is everywhere—we just have to see it, and act accordingly. Doug Peacock shows us how.