At a party many years ago, I jokingly told another guest that I’d do my best to remember his name after I published a book to great acclaim. I meant to be funny and disarming, but I bungled the delivery. I came off like a jerk. This other guest was a writer, too, and an equally self-serious one. Predictably, he took offense. He pointed his beer bottle at me. I’ll remember you too, he said, when I win my Pulitzer.

I did not shrug off his rejoinder. How could I? He may as well have suggested pistols at dawn. I was young. I was jittery with ambition. I was terrified of failure in all forms. By the time his girlfriend—who’d introduced us—returned with more beers, we were pompously debating who had better odds for a Nobel.

Flash forward to last winter, as I walked to the building where my daughter has choir practice. I wore a thick parka, but I felt my phone vibrate to announce a new email. Once inside the vestibule, I warmed my hands and checked my email to find a message from the agent who’d asked to read my latest novel. “There is really so much to admire in this manuscript,” the email began. I stopped reading and put the phone back in my coat pocket. Then marched onward to find my daughter. Already, I knew: rejection. I knew all the words that would come. I’d heard them all before.

There’s a fairly wide gap between what I expected as a preposterous young man and the writing life as I’ve lived it. I’m old enough to see how disillusionment is the price for adulthood in every vocation, not just writing and the arts. Yet, one facet of my writing life still surprises me with its wicked gleam. Once, I believed as a writer my most important skill would be knowing how to lay words in a line that’s solid as a cut stone wall. Nope. Turns out the most important skill for me as a writer, the skill I can’t live without, and the one that took the longest to learn, is a skill for failure.

OFFSTAGE VOICE (Indignantly): Your Honor, the defendant is beating around the bush. For the record, can he state plainly that he has not, I repeat, not yet won a literary prize of any kind, or general acclaim, or even, I believe, published a real book, yes? Is that right? Can that be right, after all these years?

Yes, yes, that’s true, all of it. I’ll be specific, then: I graduated from an MFA program over 21 years ago now. I was not idle during those years. But it took 12 years for me to write and revise a story to the point that a journal was willing to publish it. The rewriting wasn’t the problem, although I wrote a lot of bad prose, too; the problem was submitting.

Once upon a time, any query that I sent out involved printing an excerpt or a story and sending the pages in the post. I had a stockpile of Uline envelopes, printer paper reams, spare toner, and stamps, always stamps. I was a regular at the drop box in the post office in Newark, N.J., the tired one near the office where I worked. Eventually, the postal tide carried rejections to me in my own self-addressed envelopes. I was prepared for cold, impersonal rejections. I hated to see them, but they were expected. However, nothing prepared me for the kind ones. For the almost-but-not-quite-there rejections, the let downs that were almost yeses. The kindest of cuts stung the most.

“I want to stress how close this came,” wrote one editor, about a story I’d submitted. The first agent I ever queried wrote: “I found myself starting and stopping, convinced by your talent without being fully absorbed.” An editor at Grove went so far as to edit 50 pages of my manuscript before deciding, no, no, not for her. I have a photocopy of the edits; a kind gesture, but also a painful one.

As time passed, more and more people I knew began to show up, one here, one there, in The New York Times Book Review. I wrote genuine congratulatory emails to friends and I tripped to the outer boroughs for readings in book shops, but let’s be real: I felt awful. It’s not that I wished these people ill. (Except that Pulitzer guy from the party long ago. He was insufferable.) I just wanted some wins, too.

One day, I opened the NYTBR to see a large photo of someone who lived three doors down in college. Her jaunty, snazzy novel was a bestseller. I’d had no idea she was a writer before that day, that moment. The shock was like learning your wife’s high school flame is moving in next door. It doesn’t really matter. Except it totally matters.

After the world mutated into its current digital state, submissions became easier, and rejections came faster. Gmail easily captured them all, and it still allows me ready access should I wish to torture myself with re-readings. “I read this piece with great interest, and I thought the characters were beautifully done,” begins a rejection from an editor at Knopf. “I wanted to let you know,” an editor writes at the end of a rejection notice from Electric Literature, “our readers commented on the story’s smart pacing and evocative details.” Another editor, another journal: “Your piece made it to the top of the general submission pile, but we didn’t take any general submissions this year.”

I have more letters like these. Dozens. Dozens of dozens. I did my best to read each and then move on. Sometimes I complained, but I learned, as the years went on, that quiet endurance was what people expect of anyone foolish enough to harbor artistic ambition. If I complained about rejection at, say, a wedding reception, a garrulous bore with a practical degree and a smug worldview was always at hand and ready to point out that this author or that cult classic got the thumbs down from publishers a few dozen, a score, hundreds, hell, why not a thousand times? This is what you asked for, yeah?

Sometimes, a useful piece of criticism would crop up in a rejection letter. “The writing is a bit flat for our list,” said the editor of a small press, after reading my novel about an interracial marriage. How lovely it felt to get clear criticism! Flat, toneless, lacking affect? Got it. This was an observation that I could address. Briefly, I had the clarity of a writing workshop. I rewrote the entire 85,000-word novel. Doubled down on submissions. But it still didn’t sell. An editor at Random House said of that book: “I read this with great interest, and thought the characters were beautifully done, and the writing was lovely, but ultimately, the stakes just didn’t seem to be high enough.”

The failure of that novel—my third since graduate school—was a turning point for me, a moment when I saw it clearly spelled out that perhaps I just plain wasn’t good at something crucial to fiction. I could write crafty sentences, even create plausible characters, but could I make a reader care?

People talk about fiction sometimes as if the elementals are so simple. Make sure your characters want something! Make sure there are stakes! Make sure the prose rings like a wine glass when you tap it! As if these attributes rose out of simple decisions made on a line-by-line basis. Yes, they do. But there’s also something more. There must be. Or else. after years of trying, wouldn’t I already have found the formula that works?

One evening after a reading that made me feel frustrated and jealous, I began writing an essay. I didn’t know that’s what it was. I was just tapping into my phone while riding on the train. But then I kept working on it after I got home. The subject: Why was I still writing? What was it that had me still trying, refusing to quit, despite failing for so long?

That meditation on failure turned into my first published essay; ironically, an essay on not succeeding was my first piece of writing to succeed in reaching an audience. I didn’t quit writing fiction per se after that. But I did write another essay. And another. I found a comfortable niche in personal essays. The canvas is smaller. The stakes are clear in the first few lines. And I fail less often when I send essays out.

Of course, I am stubborn, and I don’t always operate in a rational manner. I continue to labor at fiction. Every few years, I am swept up in the idea for a novel. I spend months and months writing doomed texts. But I don’t have the same attitude toward what will happen when I’m finished. The expectation of success is gone, so much so that I sometimes forget the point of writing a novel is to share it.

Sometimes I even see humor in rejections where no humor was intended. “There was a lot I admired about this,” said an agent who read my manuscript about the poet Sappho reappearing in the modern world. “But I couldn’t accept the idea that Sappho was somehow transplanted into the modern day.” Indeed, it would be hard to admire much about a book where you can’t accept the central premise.

Another agent once rejected a novel manuscript, but without stating why. Very well, carry on. Then, six months later, she wrote another email, apologized for the delay, and rejected me a second time. If this doesn’t make you laugh, then don’t write a book.

Not long ago, an agent rejected me and, in a few sentences, she also helped me to see how and where I fail as a fiction writer: “The gracefulness and control of your writing impressed me. [The characters] make an intriguing pair of protagonists around whom the narrative twists and unravels. As much as I admire these aspects, however, I fear the novel may ultimately be too introspective, without quite enough plot development to move the narrative along.”

Am I too introspective? Yes, I am. Do I not write fiction the way most good fiction is written? Perhaps I do not. Does this bother me? A little yes, a little no. But this is who I am. I am the Don of the Also Rans. Mr. Not Quite Good Enough. I’m a Master of Failure, and although that’s not what I set out to be, it’s something.

As a writer, I have had to learn how to fail, to fail with economy and without anger, to fail in ways that allow me to see where I am not writing well, or where I have sent my words to the wrong place. Once I learned this, everything was easier, or at least everything that had to do with rejection.

For more than a year I have been sending out into the world a new novel, Likeness; it’s starting to look like my most masterful failure yet. “There is no question that you are a very talented writer,” wrote an agent’s assistant after reading it. “This story pulled me along and kept me invested, and it’s like nothing else I’ve read in the best way.” I mean, yes, yes, right? Isn’t that what a novel should do? But, no, she went on. The book just wasn’t a fit. Her boss had no idea where to place it. It was too strange, too weird, too much its own thing.

If this is failing, then I suppose that I should have it no other way.

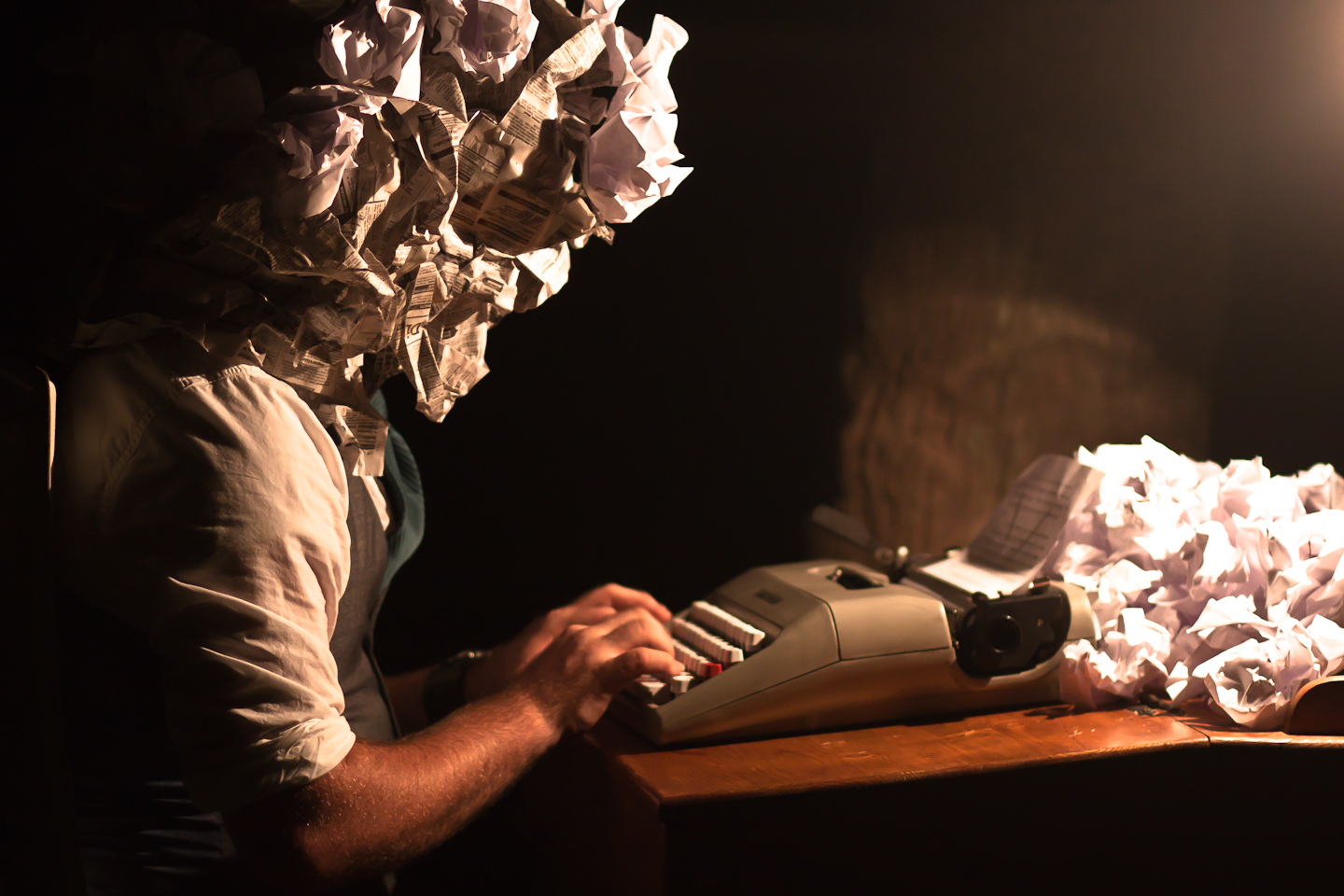

Image Credit: Flickr/DrewCoffman