We wouldn’t dream of abandoning our vast semi–annual Most Anticipated Book Previews, but we thought a monthly reminder would be helpful (and give us a chance to note titles we missed the first time around). Here’s what we’re looking out for this month. Let us know what you’re looking forward to in the comments!

Want to know about the books you might have missed? Then go read our most recent book preview. Want to help The Millions keep churning out great books coverage? Then sign up to be a member today.

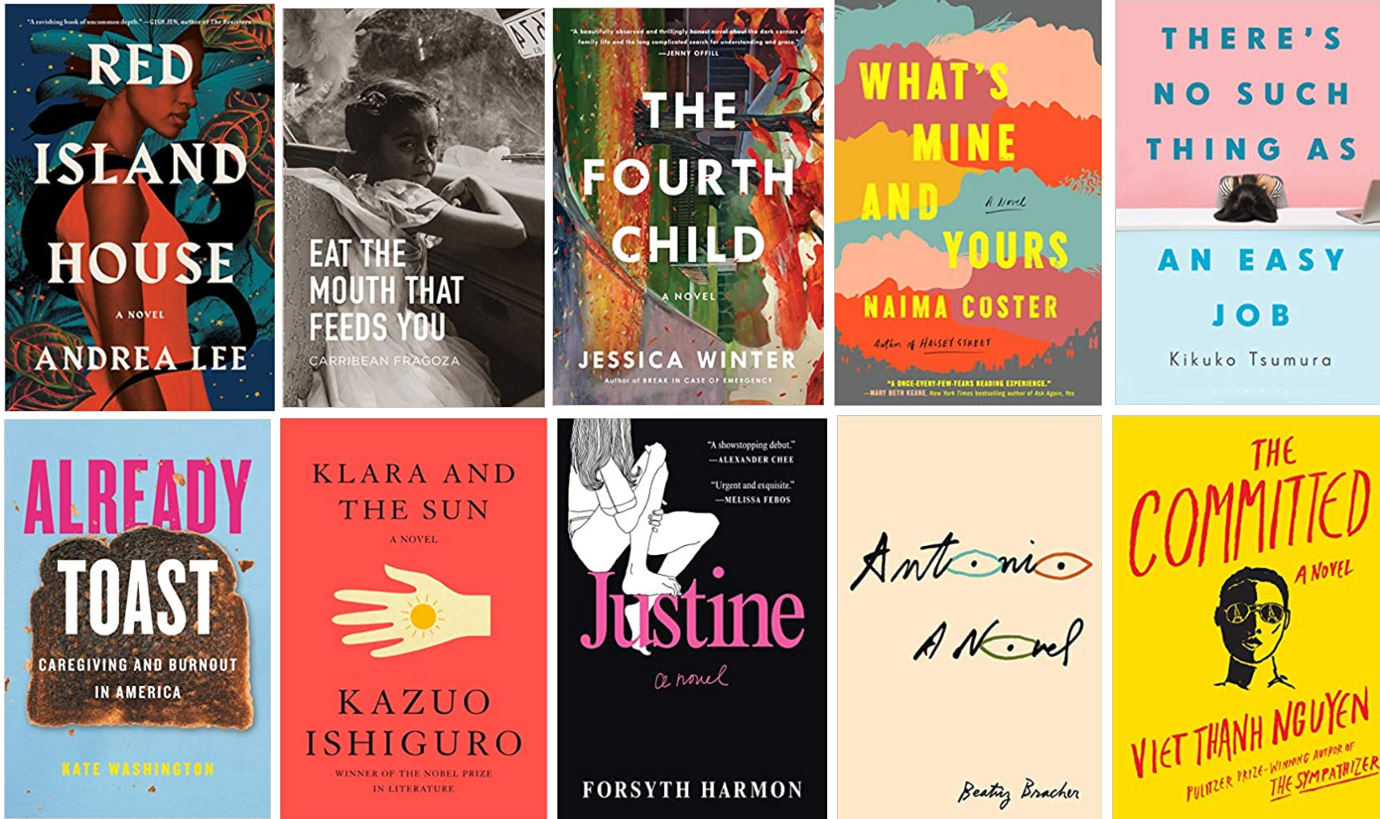

Klara and the Sun by Kazuo Ishiguro: The citation for the 2017 Novel Prize in Literature says Ishiguro has “uncovered the abyss beneath our illusory sense of connection with the world.” This new novel, his first published since the win, follows Klara, who is an Artificial Friend. While she’s an older model, she also has exceptional observational qualities. The storyline, according to the publisher, asks a fundamental question, “What does it mean to love?” The result sounds like the perfect blend of Ishiguro’s much loved books, Never Let Me Go and the Booker Prize-winning The Remains of the Day. (Claire)

Klara and the Sun by Kazuo Ishiguro: The citation for the 2017 Novel Prize in Literature says Ishiguro has “uncovered the abyss beneath our illusory sense of connection with the world.” This new novel, his first published since the win, follows Klara, who is an Artificial Friend. While she’s an older model, she also has exceptional observational qualities. The storyline, according to the publisher, asks a fundamental question, “What does it mean to love?” The result sounds like the perfect blend of Ishiguro’s much loved books, Never Let Me Go and the Booker Prize-winning The Remains of the Day. (Claire)

The Committed by Viet Thanh Nguyen: The much anticipated sequel to The Sympathizer, which won the Pulitzer Prize in Fiction, entertains as much as it offers cultural analysis. Set in 1980s Paris, the main character of The Sympathizer sells drugs, attends dinner parties with left-wing intellectuals, and turns his attention towards French culture, considering capitalism and colonization. Paul Beatty says, “Think of The Committed as the declaration of the 20th ½ Arrondissement. A squatter’s paradise for those with one foot in the grave and the other shoved halfway up Western civilization’s ass.” Sharply and humorously written, Ocean Vuong notes that the sequel asks: “How do we live in the wake of seismic loss and betrayal? And, perhaps even more critically, How do we laugh?” (Zoë)

The Committed by Viet Thanh Nguyen: The much anticipated sequel to The Sympathizer, which won the Pulitzer Prize in Fiction, entertains as much as it offers cultural analysis. Set in 1980s Paris, the main character of The Sympathizer sells drugs, attends dinner parties with left-wing intellectuals, and turns his attention towards French culture, considering capitalism and colonization. Paul Beatty says, “Think of The Committed as the declaration of the 20th ½ Arrondissement. A squatter’s paradise for those with one foot in the grave and the other shoved halfway up Western civilization’s ass.” Sharply and humorously written, Ocean Vuong notes that the sequel asks: “How do we live in the wake of seismic loss and betrayal? And, perhaps even more critically, How do we laugh?” (Zoë)

Red Island House by Andrea Lee: It’s been almost fifteen years since Andrea Lee published a book (Lost Hearts in Italy) and I’ve been sitting here waiting for it. Her fiction and memoirs often center on Black characters living abroad, and she writes with such lush and observant precision that you feel you are traveling with her. Her newest novel is set in a small village in Madagascar, where Shay, a Black professor of literature, and her wealthy Italian husband Senna, build a lavish vacation home. Unfolding over two decades, Lee’s new novel explores themes of race, class, and gender, as Shay reluctantly takes on the role of matriarch, learning to manage a household staff and estate. Kirkus calls it “a highly critical vision of how the one percent live in neocolonial paradise.” (Hannah)

Red Island House by Andrea Lee: It’s been almost fifteen years since Andrea Lee published a book (Lost Hearts in Italy) and I’ve been sitting here waiting for it. Her fiction and memoirs often center on Black characters living abroad, and she writes with such lush and observant precision that you feel you are traveling with her. Her newest novel is set in a small village in Madagascar, where Shay, a Black professor of literature, and her wealthy Italian husband Senna, build a lavish vacation home. Unfolding over two decades, Lee’s new novel explores themes of race, class, and gender, as Shay reluctantly takes on the role of matriarch, learning to manage a household staff and estate. Kirkus calls it “a highly critical vision of how the one percent live in neocolonial paradise.” (Hannah)

The Fourth Child by Jessica Winter: Winter follows her well-received debut (2016’s Break in Case of Emergency) with a multi-generational story of love, family, obligation, and guilt. The novel follows Jane from a miserable 1970s adolescence to an unexpected high school pregnancy and marriage, through the sweetness of early parenthood to the fraught complications of ideology, adoption, and life with a teenaged daughter. (Emily M.)

The Fourth Child by Jessica Winter: Winter follows her well-received debut (2016’s Break in Case of Emergency) with a multi-generational story of love, family, obligation, and guilt. The novel follows Jane from a miserable 1970s adolescence to an unexpected high school pregnancy and marriage, through the sweetness of early parenthood to the fraught complications of ideology, adoption, and life with a teenaged daughter. (Emily M.)

Mona by Pola Oloixarac (translated by Adam Morris): Mona, Pola Oloixarac’s third novel, seems a fitting book for all of us to read while looking back on 2020: the eponymous narrator is a drug-addled and sardonic, albeit much admired and Peruvian writer based in California. After she’s nominated for Europe’s most important literary prize, Mona flees to a small town near the Arctic Circle to escape her demons in a way that seems not unlike David Bowie‘s fleeing LA for bombed-out Berlin. She soon finds she hasn’t escaped hers as much as she’s locked herself up with them. According to Andrew Martin, Mona “reads as though Rachel Cusk‘s Outline Trilogy was thrown in a blender with Roberto Bolaño‘s 2666, and then lightly seasoned with the bitter flavor of Horacio Castellanos Moya.” (Anne)

Mona by Pola Oloixarac (translated by Adam Morris): Mona, Pola Oloixarac’s third novel, seems a fitting book for all of us to read while looking back on 2020: the eponymous narrator is a drug-addled and sardonic, albeit much admired and Peruvian writer based in California. After she’s nominated for Europe’s most important literary prize, Mona flees to a small town near the Arctic Circle to escape her demons in a way that seems not unlike David Bowie‘s fleeing LA for bombed-out Berlin. She soon finds she hasn’t escaped hers as much as she’s locked herself up with them. According to Andrew Martin, Mona “reads as though Rachel Cusk‘s Outline Trilogy was thrown in a blender with Roberto Bolaño‘s 2666, and then lightly seasoned with the bitter flavor of Horacio Castellanos Moya.” (Anne)

Girlhood by Melissa Febos: Fusing memoir, cultural commentary, and research, critically-acclaimed writer Febos explores the beauty and discomfort of girlhood (and womanhood) in her newest essay collection. With her signature lyricism and haunting honesty, the essays explore the ways girls inherit, create, interrogate, and rewrite the narratives of their lives. Kirkus’ starred review calls the collection “consistently illuminating, unabashedly ferocious writing.” (Carolyn)

Girlhood by Melissa Febos: Fusing memoir, cultural commentary, and research, critically-acclaimed writer Febos explores the beauty and discomfort of girlhood (and womanhood) in her newest essay collection. With her signature lyricism and haunting honesty, the essays explore the ways girls inherit, create, interrogate, and rewrite the narratives of their lives. Kirkus’ starred review calls the collection “consistently illuminating, unabashedly ferocious writing.” (Carolyn)

The Arsonist’s City by Hala Alyan: Alyan’s varied talents never cease to amaze. The award-winning author of four collections of poetry and one novel, Alyan also works as a clinical psychologist. Her newest novel touches on themes and locales familiar to those who’ve read her work including family, war, Brooklyn, and the Middle East. The Nasr family has spread across the world, but remains rooted in their ancestral home in Beirut. When the family’s new patriarch decides to sell, all must reunite to save the house and confront their secrets in a city still reeling from the impact of its past and ongoing tensions. (Jacqueline)

The Arsonist’s City by Hala Alyan: Alyan’s varied talents never cease to amaze. The award-winning author of four collections of poetry and one novel, Alyan also works as a clinical psychologist. Her newest novel touches on themes and locales familiar to those who’ve read her work including family, war, Brooklyn, and the Middle East. The Nasr family has spread across the world, but remains rooted in their ancestral home in Beirut. When the family’s new patriarch decides to sell, all must reunite to save the house and confront their secrets in a city still reeling from the impact of its past and ongoing tensions. (Jacqueline)

Abundance by Jakob Guanzon: This debut novel centers around a struggling Filipino-American father and son, Henry and Junior. Evicted from their trailer, they now live in their truck and are trying to scramble a life back together. The book’s formal innovation lies in its structure, which is organized around money: each chapter tallies the duo’s debit and credit, in a gesture toward the profound anxieties and inequalities around debt, work, and addiction in contemporary America. (Jacqueline)

Abundance by Jakob Guanzon: This debut novel centers around a struggling Filipino-American father and son, Henry and Junior. Evicted from their trailer, they now live in their truck and are trying to scramble a life back together. The book’s formal innovation lies in its structure, which is organized around money: each chapter tallies the duo’s debit and credit, in a gesture toward the profound anxieties and inequalities around debt, work, and addiction in contemporary America. (Jacqueline)

What’s Mine and Yours by Naima Coster: From the author of the acclaimed novel Halsey Street (finalist for a Kirkus Prize) comes a story of family, race, and friendship. Opening in the 1990s and extending to the present, the book follows two families in Piedmont, NC, one white, one Black. Living on separate sides of town, they live separate lives until the local school’s integration efforts set off a chain of events that will bond the families to each other in profound and unexpected ways. (Jacqueline)

What’s Mine and Yours by Naima Coster: From the author of the acclaimed novel Halsey Street (finalist for a Kirkus Prize) comes a story of family, race, and friendship. Opening in the 1990s and extending to the present, the book follows two families in Piedmont, NC, one white, one Black. Living on separate sides of town, they live separate lives until the local school’s integration efforts set off a chain of events that will bond the families to each other in profound and unexpected ways. (Jacqueline)

The Seed Keeper by Diane Wilson: After her father doesn’t return from checking his traps near their home, Rosalie Iron Wing, a Dakota girl who’s grown up surrounded by the woods and stories of plants, is sent to live with a foster family. Decades later, widowed and grieving, she returns to her childhood home to confront the past and find identity and community — and a cache of seeds, passed down from one generation of women to the next. The first novel from Dakota writer Diane Wilson, “The Seed Keeper invokes the strength that women, land, and plants have shared with one another through the generations,” writes Robin Wall Kimmerer. (Kaulie)

The Seed Keeper by Diane Wilson: After her father doesn’t return from checking his traps near their home, Rosalie Iron Wing, a Dakota girl who’s grown up surrounded by the woods and stories of plants, is sent to live with a foster family. Decades later, widowed and grieving, she returns to her childhood home to confront the past and find identity and community — and a cache of seeds, passed down from one generation of women to the next. The first novel from Dakota writer Diane Wilson, “The Seed Keeper invokes the strength that women, land, and plants have shared with one another through the generations,” writes Robin Wall Kimmerer. (Kaulie)

How Beautiful We Were by Im bolo Mbue: In a follow-up to Mbue’s celebrated Behold the Dreamers, winner of the 2017 PEN/Faulkner award, How Beautiful We Were tells a story of environmental exploitation and a fictional African village’s fight to save itself. An American oil company’s leaking pipelines are poisoning the land and children of Kosawa, and in the face of government inaction the villagers strike back, sparking a series of small revolutions with outsized impact. Kosawa’s story is told by the family of Thula, a village girl who grows into a charismatic revolutionary and who Sigrid Nunez calls “a heroine for our time.” (Kaulie)

bolo Mbue: In a follow-up to Mbue’s celebrated Behold the Dreamers, winner of the 2017 PEN/Faulkner award, How Beautiful We Were tells a story of environmental exploitation and a fictional African village’s fight to save itself. An American oil company’s leaking pipelines are poisoning the land and children of Kosawa, and in the face of government inaction the villagers strike back, sparking a series of small revolutions with outsized impact. Kosawa’s story is told by the family of Thula, a village girl who grows into a charismatic revolutionary and who Sigrid Nunez calls “a heroine for our time.” (Kaulie)

Eat the Mouth that Feeds You by Carribean Fragoza: Fragoza’s surreal and gothic stories, focused on Latinx, Chicanx, and immigrant women’s voices, are sure to surprise and move readers. Natalia Sylvester states, “Like the Chicanx women whose voices she centers, Carribean Fragoza’s writing doesn’t flinch. It is sharp and dream-like, tender-hearted and brutal, carved from the violence and resilience of generations past and present.” Eat the Mouth That Feeds You explores themes of lineage, motherhood, violence, and much more. Héctor Tobar writes that this short story collection “establishes Fragoza as an essential and important new voice in American fiction.” (Zoë)

Eat the Mouth that Feeds You by Carribean Fragoza: Fragoza’s surreal and gothic stories, focused on Latinx, Chicanx, and immigrant women’s voices, are sure to surprise and move readers. Natalia Sylvester states, “Like the Chicanx women whose voices she centers, Carribean Fragoza’s writing doesn’t flinch. It is sharp and dream-like, tender-hearted and brutal, carved from the violence and resilience of generations past and present.” Eat the Mouth That Feeds You explores themes of lineage, motherhood, violence, and much more. Héctor Tobar writes that this short story collection “establishes Fragoza as an essential and important new voice in American fiction.” (Zoë)

Body of Stars by Laura Maylene Walter: A dystopian novel about fortune-telling and rape culture set in a world where women’s fates are inscribed on their bodies. Of the novel Anne Valente writes, “Through the lens of dystopia, this incandescent debut novel holds a critical mirror up to our world’s limitations on gender and the violence of those restraints, while it also forges a bold vision for agency, self-determination and freedom. Through and through, this is a powerful and luminous book.” (Lydia)

Body of Stars by Laura Maylene Walter: A dystopian novel about fortune-telling and rape culture set in a world where women’s fates are inscribed on their bodies. Of the novel Anne Valente writes, “Through the lens of dystopia, this incandescent debut novel holds a critical mirror up to our world’s limitations on gender and the violence of those restraints, while it also forges a bold vision for agency, self-determination and freedom. Through and through, this is a powerful and luminous book.” (Lydia)

There’s No Such Thing as an Easy Job by Kikuko Tsumura (translated by Polly Barton): Tsumura’s novel begins with an unnamed narrator constantly watching someone. It is her job, and she’d been given a rule “not to fast-forward the footage,” except if her target is sleeping. She ponders how much money she spends on eye drops from having to keep her gaze fixed. “It was weird,” she thinks, “because I worked such long hours, and yet, even while working, I was basically doing nothing. I’d come to the conclusion that there were very few jobs in the world that ate up as much time and as little brainpower as watching over the life of a novelist who lived alone and worked from home.” A nearly hypnotic book that shifts between despair and transcendence. (Nick R.)

There’s No Such Thing as an Easy Job by Kikuko Tsumura (translated by Polly Barton): Tsumura’s novel begins with an unnamed narrator constantly watching someone. It is her job, and she’d been given a rule “not to fast-forward the footage,” except if her target is sleeping. She ponders how much money she spends on eye drops from having to keep her gaze fixed. “It was weird,” she thinks, “because I worked such long hours, and yet, even while working, I was basically doing nothing. I’d come to the conclusion that there were very few jobs in the world that ate up as much time and as little brainpower as watching over the life of a novelist who lived alone and worked from home.” A nearly hypnotic book that shifts between despair and transcendence. (Nick R.)

Acts of Desperation by Megan Nolan: Nolan, a columnist and writer for The New Statesman, Vice, and other places, depicts a young couple’s dysfunctional relationship and its aftermath in her debut. In 2012, the unnamed narrator becomes infatuated with an art critic named Ciaran, who seems “undeniably whole” in contrast to the people around him. The two begin dating, and things quickly become toxic, with Ciaran insulting the narrator’s friends and peppering her with cruel remarks. Throughout, we see glimpses of the narrator in 2019, when she’s reflecting on her past and working to move on from Ciaran. (Thom)

Acts of Desperation by Megan Nolan: Nolan, a columnist and writer for The New Statesman, Vice, and other places, depicts a young couple’s dysfunctional relationship and its aftermath in her debut. In 2012, the unnamed narrator becomes infatuated with an art critic named Ciaran, who seems “undeniably whole” in contrast to the people around him. The two begin dating, and things quickly become toxic, with Ciaran insulting the narrator’s friends and peppering her with cruel remarks. Throughout, we see glimpses of the narrator in 2019, when she’s reflecting on her past and working to move on from Ciaran. (Thom)

Justine by Forsyth Harmon: Set in 1999 on Long Island, Harmon’s illustrated novel follows Ali, a lonely teenager, as she falls under the spell of the beautiful and alluring Justine, a cashier at the neighborhood Stop & Shop. As the girls become closer, swiftly and intensely, their relationship becomes increasingly fraught. With no shortage of praise—”Show-stopping” (Alexander Chee); “Urgent and exquisite” (Melissa Febos); ” Pulsingly alive” (Kristen Radtke); “Nervy, exacting illustrations and effortles prose” (Catherine Lacy)—the debut is a complicated and nuanced portrait of female adolescence. (Carolyn)

Justine by Forsyth Harmon: Set in 1999 on Long Island, Harmon’s illustrated novel follows Ali, a lonely teenager, as she falls under the spell of the beautiful and alluring Justine, a cashier at the neighborhood Stop & Shop. As the girls become closer, swiftly and intensely, their relationship becomes increasingly fraught. With no shortage of praise—”Show-stopping” (Alexander Chee); “Urgent and exquisite” (Melissa Febos); ” Pulsingly alive” (Kristen Radtke); “Nervy, exacting illustrations and effortles prose” (Catherine Lacy)—the debut is a complicated and nuanced portrait of female adolescence. (Carolyn)

Already Toast by Kate Washington: In her debut memoir, Washington—an essayist and dining critic for The Sacramento Bee—writes about her struggle to care for her cancer-stricken husband. As she became progressively more burnt out while being the full-time caregiver of her grievously ill husband and two young children, Washington realized she was only one of millions who were silently suffering because of countless cultural, bureaucratic, and policy failures. Kirkus writes, “A startling, hard-hitting story of a family medical disaster made worse by cultural insensitivities to caregivers.”(Carolyn)

Already Toast by Kate Washington: In her debut memoir, Washington—an essayist and dining critic for The Sacramento Bee—writes about her struggle to care for her cancer-stricken husband. As she became progressively more burnt out while being the full-time caregiver of her grievously ill husband and two young children, Washington realized she was only one of millions who were silently suffering because of countless cultural, bureaucratic, and policy failures. Kirkus writes, “A startling, hard-hitting story of a family medical disaster made worse by cultural insensitivities to caregivers.”(Carolyn)

Antonio by Beatriz Bracher (translated by Adam Morris): Benjamin, a graphic designer living in Rio de Janeiro, is on the cusp of becoming a father (to a baby boy named Antonio) when he learns a devastating, life-altering family secret. The people most intimately involved, who can answer Benjamin’s questions, are dead, so he turns to the people closest to them—who offer the father-to-be their versions of the truth. With starred reviews from both Kirkus and Publishers Weekly, the former called novel “elegant and nuanced,” and the latter called it “spellbinding and surprising” and Bracher “one of the most fascinating contemporary Brazilian writers.” (Carolyn)

Antonio by Beatriz Bracher (translated by Adam Morris): Benjamin, a graphic designer living in Rio de Janeiro, is on the cusp of becoming a father (to a baby boy named Antonio) when he learns a devastating, life-altering family secret. The people most intimately involved, who can answer Benjamin’s questions, are dead, so he turns to the people closest to them—who offer the father-to-be their versions of the truth. With starred reviews from both Kirkus and Publishers Weekly, the former called novel “elegant and nuanced,” and the latter called it “spellbinding and surprising” and Bracher “one of the most fascinating contemporary Brazilian writers.” (Carolyn)

Last Call by Elon Green: In the 1980s and 1990s, The Last Call Killer, a long-forgotten serial murderer, preyed on gay men in New York City. Green, a journalist, explores the heinous crimes, the victims’ lives, and the decades-long investigation in his first book. “Elon Green tenaciously yet gracefully investigates a time when so many lived in secret, and those secrets made them vulnerable to predation,” writes Robert Kolker. “A resonant, powerful book.” (Carolyn)

Last Call by Elon Green: In the 1980s and 1990s, The Last Call Killer, a long-forgotten serial murderer, preyed on gay men in New York City. Green, a journalist, explores the heinous crimes, the victims’ lives, and the decades-long investigation in his first book. “Elon Green tenaciously yet gracefully investigates a time when so many lived in secret, and those secrets made them vulnerable to predation,” writes Robert Kolker. “A resonant, powerful book.” (Carolyn)

The Phone Booth at the Edge of the World by Laura Imai Messina (translated by Lucy Rand): Already an international bestseller in 21 countries, Messina’s English-language debut follows Yui, a mother who lost her mother and daughter during the Great Tōhoku Earthquake on March 11, 2011. Reeling from the loss, Yui struggles to keep herself afloat while dealing with her grief. When she hears about an old phone booth that allows people to talk to their lost loved ones, Yui travels there to find closure and healing. (Carolyn)

The Phone Booth at the Edge of the World by Laura Imai Messina (translated by Lucy Rand): Already an international bestseller in 21 countries, Messina’s English-language debut follows Yui, a mother who lost her mother and daughter during the Great Tōhoku Earthquake on March 11, 2011. Reeling from the loss, Yui struggles to keep herself afloat while dealing with her grief. When she hears about an old phone booth that allows people to talk to their lost loved ones, Yui travels there to find closure and healing. (Carolyn)

A History of Scars by Laura Lee: In her debut memoir, Lee’s essays explore the pyschological and emotional scars left behind by things like sexuality, trauma, mental illness, and complicated parent-child relationships. Library Journal says, ” “Ultimately, what Laura Lee created is a display of raw humanity that is both powerful and vulnerable.” (Carolyn)

A History of Scars by Laura Lee: In her debut memoir, Lee’s essays explore the pyschological and emotional scars left behind by things like sexuality, trauma, mental illness, and complicated parent-child relationships. Library Journal says, ” “Ultimately, what Laura Lee created is a display of raw humanity that is both powerful and vulnerable.” (Carolyn)