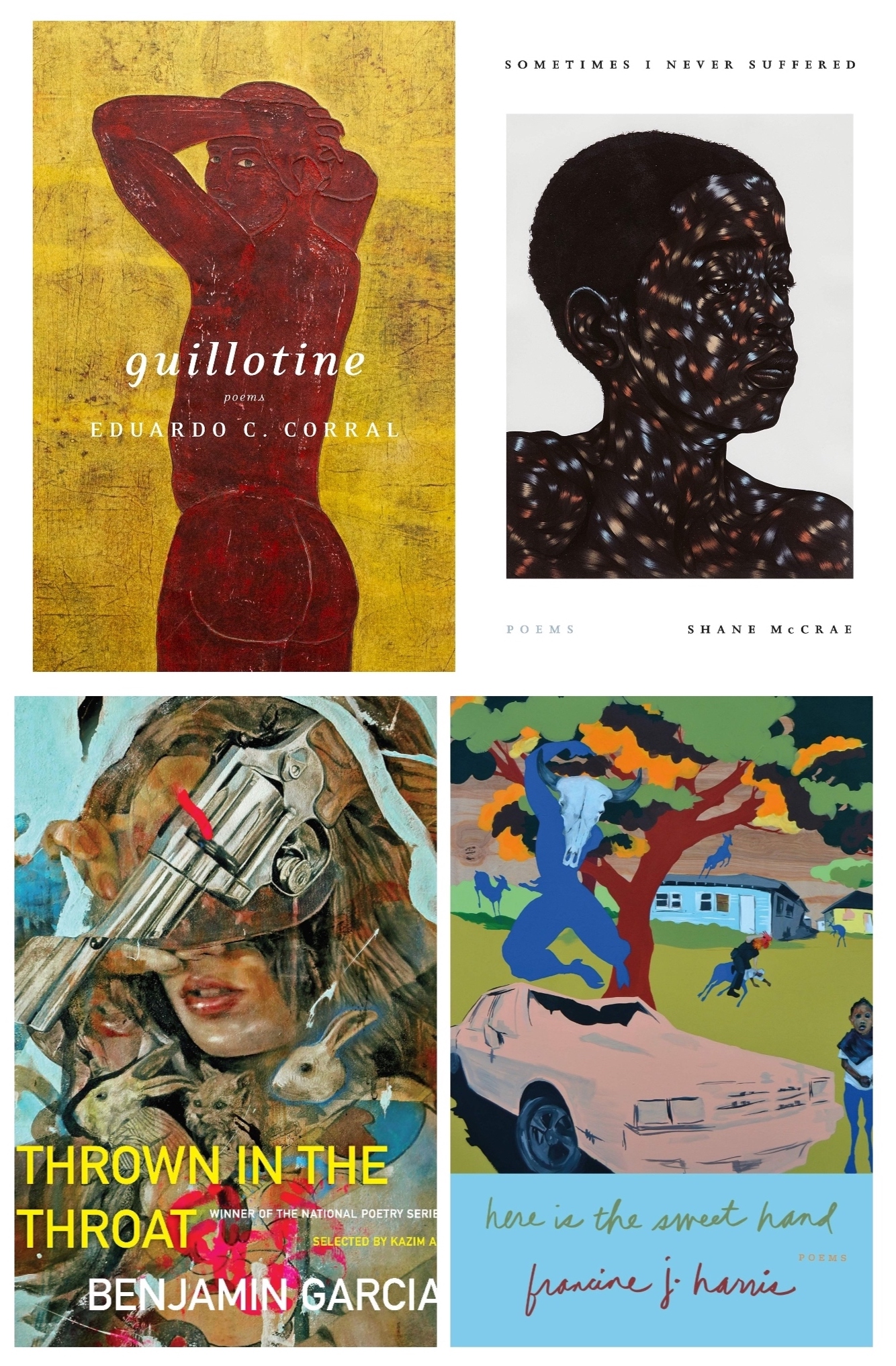

Here are six notable books of poetry publishing this month.

Guillotine by Eduardo C. Corral

An excellent second collection. “Testaments Scratched into a Water Station Barrel,” an ambitious sequence told in shifting intervals, tells the story of those crossing the border from Mexico to Arizona. The water station barrel provides a much-needed salve from the treacherous journey. In the far-reaching poem, dreams, hallucinations, memories, and desires intertwine. No matter what his subject, Corral is a gifted storyteller, precise and dizzying with his imagery: “After my mother’s death, I found, in a box, / her wedding dress. / As I lifted the lid, a stench corkscrewed / into my nostrils: /the dress had curdled like milk.” Later: “Dusk, here, is stunning. Yesterday, I woke to ants crawling / over my body, / to ants crawling / over / the body on the cross around my neck.” I can’t help but linger over his finely-wrought phrases that anchor each poem, as in “Saguaro”: “Sonoran / pictograph ablaze // in cloud shadow, / glass lighting.” From “To Juan Doe #234”: “In Border Patrol / jargon, the word // for border crossers is the same whether / they’re alive or dead.” Corral can capture a world in a poem’s single scene, as in “Córdoba,” when the narrator looks at his reflection in a bathroom mirror. “I reach / to clean, with my thumb” the mirror “speckled / with toothpaste” and blood, but he quickly pulls back his hand. “I don’t touch mirrors. It’s wrong, / my father always said, // to touch a man.” An accomplished book in both style and sense.

An excellent second collection. “Testaments Scratched into a Water Station Barrel,” an ambitious sequence told in shifting intervals, tells the story of those crossing the border from Mexico to Arizona. The water station barrel provides a much-needed salve from the treacherous journey. In the far-reaching poem, dreams, hallucinations, memories, and desires intertwine. No matter what his subject, Corral is a gifted storyteller, precise and dizzying with his imagery: “After my mother’s death, I found, in a box, / her wedding dress. / As I lifted the lid, a stench corkscrewed / into my nostrils: /the dress had curdled like milk.” Later: “Dusk, here, is stunning. Yesterday, I woke to ants crawling / over my body, / to ants crawling / over / the body on the cross around my neck.” I can’t help but linger over his finely-wrought phrases that anchor each poem, as in “Saguaro”: “Sonoran / pictograph ablaze // in cloud shadow, / glass lighting.” From “To Juan Doe #234”: “In Border Patrol / jargon, the word // for border crossers is the same whether / they’re alive or dead.” Corral can capture a world in a poem’s single scene, as in “Córdoba,” when the narrator looks at his reflection in a bathroom mirror. “I reach / to clean, with my thumb” the mirror “speckled / with toothpaste” and blood, but he quickly pulls back his hand. “I don’t touch mirrors. It’s wrong, / my father always said, // to touch a man.” An accomplished book in both style and sense.

Sometimes I Never Suffered by Shane McCrae

McCrae is a contemporary mythmaker, a poet who is able to lift his art to a spiritual plane. His new book continues a sustained, complex engagement with the ineffable. In “The Hastily Assembled Angel Falls at the Beginning of the World,” “clouds was the last word / He heard the other angels shouting as / They shoved him,” his body too far to hear them, but he “saw their mouths making / Shapes that were not clouds.” McCrae’s method of snipped lines—imbued with breath-spaces—create discrete phrases within each line, creating a layering of the abstract and specific. Near the end of the poem, “as he fell he watched the clouds / Becoming strange abstract the way another / Angel would watch a species go extinct,” the effect feels hymnal, symphonic. His ambition and fervor bring to mind Gerard Manley Hopkins, as does his interest in the body as image of God. The angel drifts through these early poems: he “wanders…through centuries of cities / And countries and millennia of cities / And countries and of women and of men.” Next is a sequence of poems about Jim Limber, an adopted, mixed-race son of Jefferson Davis, whose own ethereal drifting sometimes mirrors, sometimes inverts the view of the angel. Limber “yelled when Yankees took me” from his family, and in that way, “home / Follows your sorrow so it is like Heaven.” Heaven is where he might soon go, and where he wonders if he will become an angel himself: “Will I still be my body if it changes.” Limber and Davis speak in “Old Times There,” a short verse play embedded in the book—which is followed by sections on Limbo and Heaven, where Limber used to hear “the older slaves / Talking about the fields of bliss.” In Heaven, “They get to keep their bodies and their minds die.” McCrae is one of the finest poets of God and the unknown.

McCrae is a contemporary mythmaker, a poet who is able to lift his art to a spiritual plane. His new book continues a sustained, complex engagement with the ineffable. In “The Hastily Assembled Angel Falls at the Beginning of the World,” “clouds was the last word / He heard the other angels shouting as / They shoved him,” his body too far to hear them, but he “saw their mouths making / Shapes that were not clouds.” McCrae’s method of snipped lines—imbued with breath-spaces—create discrete phrases within each line, creating a layering of the abstract and specific. Near the end of the poem, “as he fell he watched the clouds / Becoming strange abstract the way another / Angel would watch a species go extinct,” the effect feels hymnal, symphonic. His ambition and fervor bring to mind Gerard Manley Hopkins, as does his interest in the body as image of God. The angel drifts through these early poems: he “wanders…through centuries of cities / And countries and millennia of cities / And countries and of women and of men.” Next is a sequence of poems about Jim Limber, an adopted, mixed-race son of Jefferson Davis, whose own ethereal drifting sometimes mirrors, sometimes inverts the view of the angel. Limber “yelled when Yankees took me” from his family, and in that way, “home / Follows your sorrow so it is like Heaven.” Heaven is where he might soon go, and where he wonders if he will become an angel himself: “Will I still be my body if it changes.” Limber and Davis speak in “Old Times There,” a short verse play embedded in the book—which is followed by sections on Limbo and Heaven, where Limber used to hear “the older slaves / Talking about the fields of bliss.” In Heaven, “They get to keep their bodies and their minds die.” McCrae is one of the finest poets of God and the unknown.

Here Is the Sweet Hand by francine j. harris

harris’s poems teem with emotion, but there’s a control to her lines that feels so clever—as in “Junebug,” the lines “All night I put up your / bad plans on a map” can unfold in so many directions, but the subsequent lines offer even another route: “Your hands / go sideways, like a diagonal gnat / of blankets.” harris has spoken about how poets should play with language, and inherent in her play is a willingness to shift and swing among time and subject. Later in “Junebug”: “in her // photographs she has on the best / lip gloss I’ve ever noticed. Maybe now that I have // stopped flailing my arms and throwing / myself against the walls.” Poems like “Unlike my sister” reveal that harris is original in syntax and rhythm: the poems in this collection never play quite the same song, as if their form keeps us active and alert. “I don’t have children I won’t bring to the city,” the narrator starts, “or to the city beach, or the monkey bars. / I don’t curl my eyelashes in the mirror with a whiteness. or a woman. or an iron bar.” Poems like “Tardigrade” often seem like they are written to a recipient, imbuing the poems with an acoustic touch—perhaps a warning: “I’m not saying close your eyes. I’m saying / don’t look up from your food. your table. your beer. The room is dark for a reason. keeps / everyone at a distance.”

harris’s poems teem with emotion, but there’s a control to her lines that feels so clever—as in “Junebug,” the lines “All night I put up your / bad plans on a map” can unfold in so many directions, but the subsequent lines offer even another route: “Your hands / go sideways, like a diagonal gnat / of blankets.” harris has spoken about how poets should play with language, and inherent in her play is a willingness to shift and swing among time and subject. Later in “Junebug”: “in her // photographs she has on the best / lip gloss I’ve ever noticed. Maybe now that I have // stopped flailing my arms and throwing / myself against the walls.” Poems like “Unlike my sister” reveal that harris is original in syntax and rhythm: the poems in this collection never play quite the same song, as if their form keeps us active and alert. “I don’t have children I won’t bring to the city,” the narrator starts, “or to the city beach, or the monkey bars. / I don’t curl my eyelashes in the mirror with a whiteness. or a woman. or an iron bar.” Poems like “Tardigrade” often seem like they are written to a recipient, imbuing the poems with an acoustic touch—perhaps a warning: “I’m not saying close your eyes. I’m saying / don’t look up from your food. your table. your beer. The room is dark for a reason. keeps / everyone at a distance.”

Anodyne by Khadijah Queen

Her new book opens with a flash of prescience: “In the Event of an Apocalypse, Be Ready to Die,” says the title, “But do also remember galleries, gardens, / herbaria.” Anodyne is full of these “repositories of beauty” among distress, enabling Queen to refute suffering with flits of joy. “The Rule of Opulence” is a beautiful meditation on transcendence: “Bamboo shoots on my grandmother’s side path / grow denser every year they’re harvested for nuisance.” The narrator’s grandmother has, for nine decades, “seen every season stretch out of shape.” The narrator contemplates her on Mother’s Day, although she’s “always disbelieved permanence—newness a habit, / change an addiction—but the difficulty of staying put / lies not in the discipline of upkeep,” she ponders, but in the world’s constant nature. After all, there’s “nothing more permanent than the cracked flagstone / path to the door, that uneven earth, shifting.” Lines from a later poem echo Queen’s refrain of how we might remain in our entropic world: “Who are we? Orion songs, missed evergreens, bodies // Looped into every surface, looped // Insistent into struggle—like heirloom seeds, rising in scatter.”

Her new book opens with a flash of prescience: “In the Event of an Apocalypse, Be Ready to Die,” says the title, “But do also remember galleries, gardens, / herbaria.” Anodyne is full of these “repositories of beauty” among distress, enabling Queen to refute suffering with flits of joy. “The Rule of Opulence” is a beautiful meditation on transcendence: “Bamboo shoots on my grandmother’s side path / grow denser every year they’re harvested for nuisance.” The narrator’s grandmother has, for nine decades, “seen every season stretch out of shape.” The narrator contemplates her on Mother’s Day, although she’s “always disbelieved permanence—newness a habit, / change an addiction—but the difficulty of staying put / lies not in the discipline of upkeep,” she ponders, but in the world’s constant nature. After all, there’s “nothing more permanent than the cracked flagstone / path to the door, that uneven earth, shifting.” Lines from a later poem echo Queen’s refrain of how we might remain in our entropic world: “Who are we? Orion songs, missed evergreens, bodies // Looped into every surface, looped // Insistent into struggle—like heirloom seeds, rising in scatter.”

Thrown in the Throat by Benjamin Garcia

Reflecting on “Warrior Song,” one of the first poems in his debut collection, Garcia has spoken of his usage of first person plural in the poem—how that conception of “we” rather than the “I” of earlier drafts felt more appropriate. “Nothing I have done has been on my own. Our communities—we—have been resisting together.” That collective spirit anchors “Warrior Song”—“When we had no faith luck / was our faith. When we have finished / death will be our luck”—and Garcia’s entire collection. Here the collective is fraught with tension, as when “mom didn’t know I was gay / because she chose not to see,” and later, “My father // didn’t raise me to be a girly man, a fact that might bother him, / except for the other fact: he didn’t raise me.” Garcia returns to a refrain of poems titled “The Language in Question” that ponders language, meaning, and result: “defying gravity after all // isn’t the same as flying”—taken together, these poems affirm identity through distinction, and offer the narrator power. “Confession: during prayers, I don’t close my eyes,” Garcia writes. “Nobody knows this except the other people who don’t close their eyes.”

Reflecting on “Warrior Song,” one of the first poems in his debut collection, Garcia has spoken of his usage of first person plural in the poem—how that conception of “we” rather than the “I” of earlier drafts felt more appropriate. “Nothing I have done has been on my own. Our communities—we—have been resisting together.” That collective spirit anchors “Warrior Song”—“When we had no faith luck / was our faith. When we have finished / death will be our luck”—and Garcia’s entire collection. Here the collective is fraught with tension, as when “mom didn’t know I was gay / because she chose not to see,” and later, “My father // didn’t raise me to be a girly man, a fact that might bother him, / except for the other fact: he didn’t raise me.” Garcia returns to a refrain of poems titled “The Language in Question” that ponders language, meaning, and result: “defying gravity after all // isn’t the same as flying”—taken together, these poems affirm identity through distinction, and offer the narrator power. “Confession: during prayers, I don’t close my eyes,” Garcia writes. “Nobody knows this except the other people who don’t close their eyes.”

Radiant Obstacles by Luke Hankins

“Why is it so tempting / to say the love of a thing / is dependent on its loss?” Hankins considers the paradoxes of holiness in this new collection, his questions often focused on our distance from the divine. It is only human, of course, to seek to lessen that distance, through contemplation or remaking the divine in one’s own image: “I could not presume to know the Maker’s mind, / but I know something of my own— / I could not bear / to make sure magnificent and fleeting things.” Hankins’s narrative voice reaches toward that imperceptible but desirous bridge between mortal and immortal, temporary and eternal. In “Even the River,” “All of nature / seems to address and blame me.” The narrator, physically penitential with “palms upturned,” also offers his “willingness to hold / the guilt that finds no other place to rest.” The natural world returns often in these poems, as a spiritual presence, a creator of awe (in both its inviting and troubling senses): “I feel so far from the meaning of the earth. / It is silent. It lives but does not speak.” And even when we do get seemingly close to the heart of it all—the beautiful vanity of affirming the self—the narrator ultimately ponders Ecclesiastes 1:2-4; that soon enough we become nothing but vapor.

“Why is it so tempting / to say the love of a thing / is dependent on its loss?” Hankins considers the paradoxes of holiness in this new collection, his questions often focused on our distance from the divine. It is only human, of course, to seek to lessen that distance, through contemplation or remaking the divine in one’s own image: “I could not presume to know the Maker’s mind, / but I know something of my own— / I could not bear / to make sure magnificent and fleeting things.” Hankins’s narrative voice reaches toward that imperceptible but desirous bridge between mortal and immortal, temporary and eternal. In “Even the River,” “All of nature / seems to address and blame me.” The narrator, physically penitential with “palms upturned,” also offers his “willingness to hold / the guilt that finds no other place to rest.” The natural world returns often in these poems, as a spiritual presence, a creator of awe (in both its inviting and troubling senses): “I feel so far from the meaning of the earth. / It is silent. It lives but does not speak.” And even when we do get seemingly close to the heart of it all—the beautiful vanity of affirming the self—the narrator ultimately ponders Ecclesiastes 1:2-4; that soon enough we become nothing but vapor.