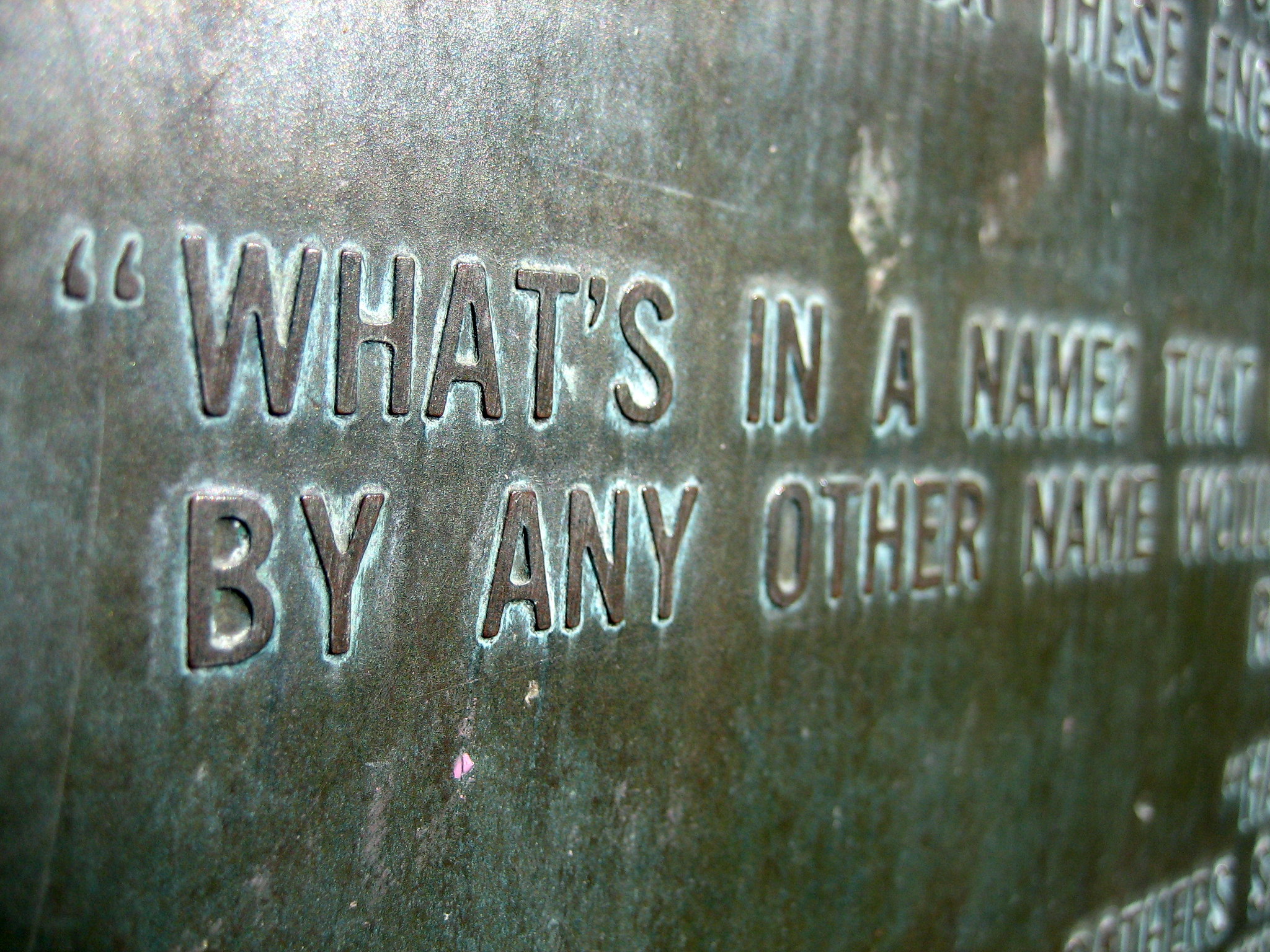

Character names are a strange aspect of the novel, one E.M. Forster neglected to cover. They are so important, so central to a reader’s experience with a book, and yet so often attended to at the last moment, if at all. From personal experience, character names often adhere early on in a draft, and it is only with an immense conscious effort that an author is able to pry the original handle away from its jealous owner. They run the gamut from the naturalistic and seemingly inconsequential (Patrick Melrose, Joseph Marlowe) to artificial and significant (Oedipa Maas, Thomas Gradgrind); from the subtle (India Bridge) to the obvious (Stephen Dedalus, Becky Sharp, Mr. Merdle); from the very good (Atticus Finch, Veruca Salt) to the very bad (Purity Tyler).

Good names often don’t matter all that much to the reading experience, but bad ones can be not only annoying but counterproductive and unilluminating. Desperate Characters by Paula Fox is one of my favorite novels, but the surname “Bentwood” for Otto and Sophie—as Jonathan Franzen touches on in his thoughtful foreword—is awkward and doesn’t land. It doesn’t speak to Sophie’s preternatural, almost neurasthenic sensitivity—the last thing you imagine her as is anything as solid as a piece of wood—nor does it seem to suggest anything true about the Bentwood’s strained marriage, which is in addled disarray, but is not bent. More importantly, it feels forced. You can hear the author coming up with it, and this precious quality does not serve the book, although Desperate Characters is great enough to weather this minor storm.

Good names often don’t matter all that much to the reading experience, but bad ones can be not only annoying but counterproductive and unilluminating. Desperate Characters by Paula Fox is one of my favorite novels, but the surname “Bentwood” for Otto and Sophie—as Jonathan Franzen touches on in his thoughtful foreword—is awkward and doesn’t land. It doesn’t speak to Sophie’s preternatural, almost neurasthenic sensitivity—the last thing you imagine her as is anything as solid as a piece of wood—nor does it seem to suggest anything true about the Bentwood’s strained marriage, which is in addled disarray, but is not bent. More importantly, it feels forced. You can hear the author coming up with it, and this precious quality does not serve the book, although Desperate Characters is great enough to weather this minor storm.

An ideal name, to me, conveys as much as possible about the character, while landing on this side of formulaic or self-conscious. It sounds plausible and real, but somehow resonates at a frequency that, at every appearance of the name, alerts the reader to important things about the character that it may take the entire novel to fully reveal. There are many examples of this, but the novel I’ll examine here, Edith Wharton’s The House of Mirth, offers a masterclass in the art of character naming.

Let’s start with the protagonist, Lily Bart. Consider this name as compared to the aforementioned Becky Sharp, from William Makepeace Thackeray’s Vanity Fair. “Becky” doesn’t tell us much about the character, other than perhaps in its lower class frisson. “Sharp” tells us everything we need to know about the character: the novel’s heroine is dangerous, a scheming cheat, and smarter than the procession of vain, dopey aristocrats and society wannabes who populate this teeming novel. In a sense, it’s the perfect name for her, as she is a fairly one-dimensional character, if still wonderful and exciting. She changes a bit through the book, becomes more forgiving by the end, but Sharp more or less sums it up.

Let’s start with the protagonist, Lily Bart. Consider this name as compared to the aforementioned Becky Sharp, from William Makepeace Thackeray’s Vanity Fair. “Becky” doesn’t tell us much about the character, other than perhaps in its lower class frisson. “Sharp” tells us everything we need to know about the character: the novel’s heroine is dangerous, a scheming cheat, and smarter than the procession of vain, dopey aristocrats and society wannabes who populate this teeming novel. In a sense, it’s the perfect name for her, as she is a fairly one-dimensional character, if still wonderful and exciting. She changes a bit through the book, becomes more forgiving by the end, but Sharp more or less sums it up.

Lily Bart, on the other hand, is a subtly great name that grows on you, and her, for the duration of the novel. The two names counterpoise each other and stand in the same opposition as the forces in Lily’s character. The leading edge, the face, Lily: a rare flower, beautiful and fragrant, feminine. The tailing, hidden edge, Bart: abrupt and awkward, and, if not ugly, unlovely and masculine. These are the competing qualities inside Lily, a love of beauty and comfort and a deep appreciation of aesthetics, arrayed against a tough, unsparing honesty. This honesty manifests both in her determination to attain the opulent lifestyle that befits her, and in her submerged doubt about the worthiness of this lifestyle as an all-consuming end. The Lily and the Bart aspects of her personality are always in contention, bringing her close to this or that marriage of convenience, but not allowing her to ever consummate the proceedings. As “Becky Sharp” captures the dominant note of a relatively uncomplicated character, “Lily Bart” speaks to the depth and complexity of Wharton’s heroine.

There are also the symbolic resonances: lilies are Christ’s flower, and by the end of the book, Lily has become something of a Christ figure. The final third of the novel finds her increasingly reduced in finances and social stature, living in shabby boarding houses and refusing to avail herself of the means by which she might regain her former place. This sudden morality, somewhat contrived in a character sense, positions her as a scapegoat who in the book’s schema dies for the sins of the materialistic New York upper crust. Christ is not the only martyr she evokes: St. Bartholomew was flayed alive for converting the king’s brother to Christianity. In art, he has historically been depicted as skinless—most famously, Michelangelo painted him in “The Last Judgment” holding his own skin and the knife of his martyrdom. In a novel obsessed with beauty, in which the 29-year-old heroine obsessively scans her face for any signs of incipient aging, and in which she eventually pays the ultimate cost for being too desirable, this could hardly be read as an accidental reference.

Lily’s paramour is Lawrence Selden. Lawrence is a lawyer, and the name reminds the reader of this in concert with his role as the probing moral intelligence of the book, the attorney who cross-examines New York’s dangerously unserious high society, and who questions Lily’s plan to marry a rich dullard. “Selden” is less obvious, but a great last name for this vexing hero. It summons the word seldom, descriptive of the way he dips into and out of society at his will, and of his related habit of appearing and disappearing from Lily’s life. His interactions with her in the beginning of the novel exert a tremendous influence on her thinking and moral development, but he is never quite there when she needs him most.

The name of Lily’s bête noire, Bertha Dorset, seemed strange to me at first, probably because of that “Bertha,” comically dowdy at this point, but likely fashionable 100 years ago. In any case, the name conveys Bertha’s signal quality, and the structural reason that she serves as a nemesis or counter-image of Lily—namely, that she has secured a berth in society by way of her miserable husband, George, a berth she does not intend to lose. Lily’s inability to, finally, pull the trigger and marry for money is reflected in Bertha’s amoral and remorseless maneuvering, a maneuvering that points her toward the last name, Dorset, with its posh British resonance. (Dorset was, additionally, Thomas Hardy’s birthplace and the setting for most of his books, and in a certain light, Lily recalls Tess, the lovely maiden reduced and ruined by the world.)

Perhaps the best name in this book full of great names belongs to the main villain, Gus Trenor, an enormous brute of a man who bullies and harasses Lily throughout. “Gus” is the diminutive of Augustus, which perfectly sums up this petty tyrant. He is rich and important among a small group of similarly awful people, but a speck in the grand scheme—a Caesar, or better yet, Caligula, in microscopic miniature. The surname, Trenor, is to my mind, a minor stroke of genius. It manages to connote so many words without quite landing on any of them. Tremor: his presence instills fear in Lily whenever he’s around. Trainer: he would like to train Lily and fit her into the slatternly place he imagines she belongs. Tenor: despite being a huge, gruff man, there is something waveringly high-pitched and desperate about all of Gus’s appearances. Finally, there is the simple oddness of the name. It looks like a name you might have encountered before, but have you? How, for instance, do you pronounce it? I wavered between subvocalizing it as “trainer” and “trih-nor” and never felt confident about either. This uncertainty mimics the uncertain dread that he and his wife Judy, a society doyenne who wields terrible judgmental power, produce in Lily.

A constellation of wonderfully named minor characters sketches out the firmament. Gerty Farish, Ned Silverton, the ubiquitous Van Osburghs. Though these may possess less rich resonance than the leads, there is not a boring name in the whole novel. But at last, let us turn to the famous Mrs. Peniston. What a name, what grandeur. Look at it: Peniston. I do not accept the idea that Wharton, given the attention she clearly paid to the novel’s aforementioned naming schema, somehow missed the joke, and I will not pronounce it “pin-es-ton,” as people with taste superior to mine tend to do. Julia Peniston is a matronly widow possessed of such an exceptional dullness (or dulness, in Wharton’s regrettably preferred spelling) of imagination that it shocks her into illness (ilness?) to hear a rumor of Lily being linked with Gus Trenor. The irony of this woman being named Peniston is obvious and crude, yet somehow the crudeness works, is perfect. The House of Mirth is, on a certain level, all about the crudeness behind society’s thin façade, the mercenary nature of relationships and marriage, and the way society castigates any deviation from these set strictures as a kind of scapegoating for what is plainly a sexual economy. The sexless Aunt Peniston still plays her role in upholding the patriarchal strictures of this world, disinheriting Lily based on false and vicious rumors of an affair. In no other novel would this crude sex pun be less appropriate and more perfect.

It also supports an already legible feminist reading of The House of Mirth, namely that if some of these women, Lily especially, had penises, they wouldn’t face the problems they do. Lily’s worst crime is being a woman—if she were a man, with a man’s career opportunities, she could live her life as she pleased. She could live like Lawrence Selden, who remains infuriatingly obtuse throughout the novel on this key difference in their respective options. She could work as a lawyer, go to parties when she felt like it, have her own place. She could grow the beard denoted by her surname’s German translation, and she could live in peace.

Image credit: Flickr/Jack Dorsey.