James Longley makes films and photographs.

Such is the extent of the bio on his website. When you watch Longley’s films or take in his photographs, or when you hear him speak about his work, you begin to understand that “less is more” traces through his life, art, and career. The bio’s compression belies one of the deepest and widest commitments to visual documentary—to capturing the complex dimensions and layers of an entire society, distilling them meaningfully into a two-hour film or single image—I’ve ever encountered. What’s more, Longley approaches his vocation with a simplicity that reminds us how radical a singular focus and commitment can be, in a world increasingly driven by sanctioned impatience and velocity for its own sake.

Longley’s 2006 film Iraq in Fragments was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature and an Emmy for Best Cinematography. The film was also honored with awards at the Sundance Film Festival for Best Documentary Directing, Editing, and Cinematography. His 2002 film Gaza Strip was described by J. Hoberman as “A documentary to make the stones weep.” Longley’s short films include Ejaz’s Story, Sari’s Mother, and Humankind—four short films made for Save the Children about refugee families living at Tempelhof Airport in Berlin.

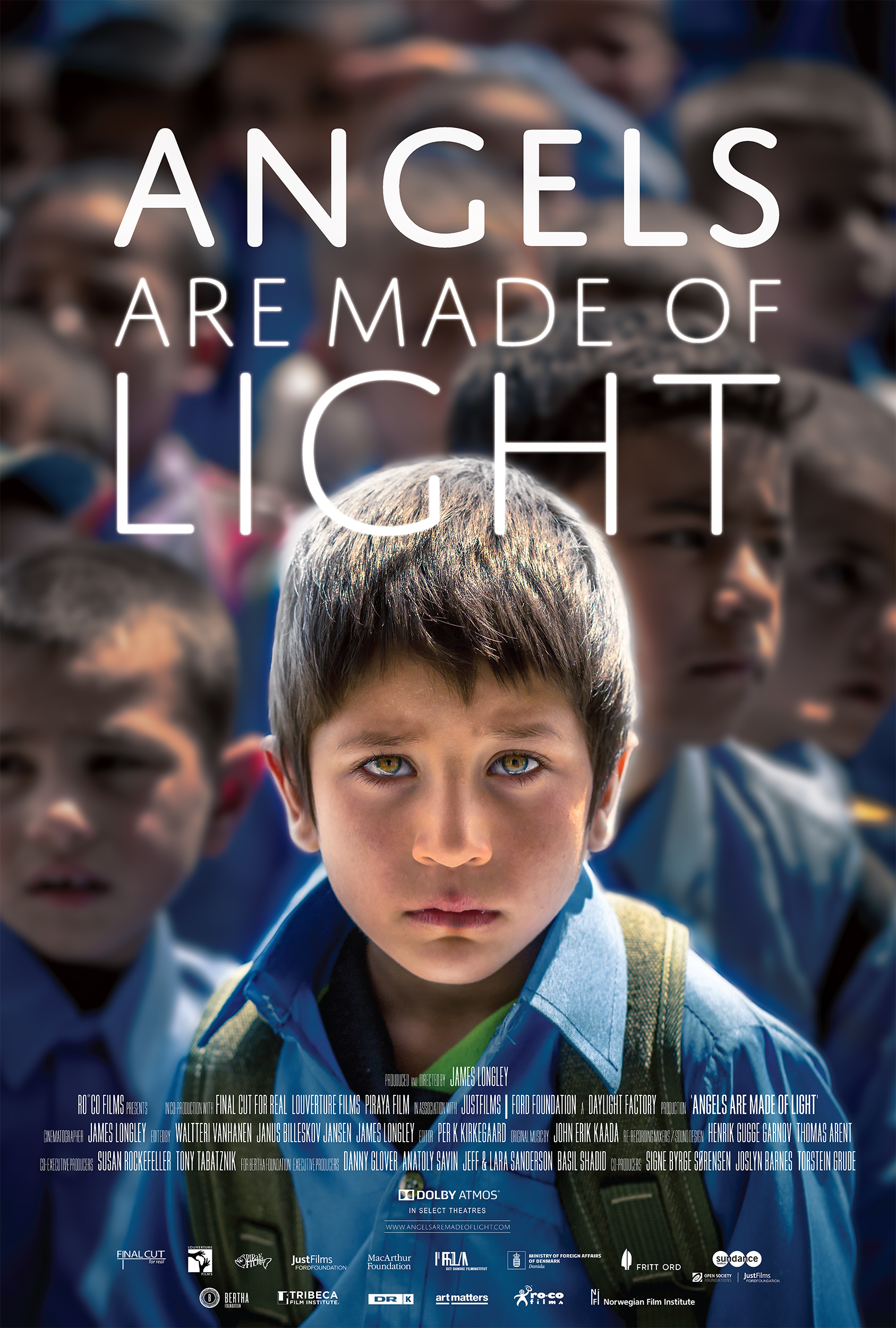

Angels Are Made of Light, Longley’s newest documentary, shot during a three year period, is an intimate portrait of students, teachers, and their families in an old neighborhood of present-day Kabul. The film opens at Film Forum in New York City on July 24th.

The Millions: Your films Iraq in Fragments (2006) and Angels Are Made of Light (2019) both bring the viewer into the viewpoint of children in war zones—Iraq and Afghanistan. What are the particular questions (and potential answers) you feel you are able to explore through the experiences and voices of children?

James Longley: I will add my short documentary, Sari’s Mother (2007), to the list.

In an ideal world what I want to show is family life. I would like to have an internal family view of the world. As best I can, I try to approximate family; and even though it seems like my films are all about children, you will also see their parents and teachers as characters in my films. (I have noticed a tendency among filmgoers to forget the adult characters and identify with the kids.) I’m making films about real people in the real world, and this is Iraq and Afghanistan we’re talking about. The society at large—everyone around where I’m working—must approve of my filming inside their close-knit communities.

In a more conservative, religious society there is a separation between genders, and also more strict social ideas about modesty. Filming inside houses is almost always out of the question, for example. In practical terms, this generally means that filming women and girls is more difficult for an outsider, particularly if the outsider is a man. In other words, what you get when you combine an American male filmmaker with a conservative religious society is a situation wherein the most practical people to film are usually old men and boys.

Because I wanted to create a well-rounded view of Afghanistan, I took pains to include the voices of women and girls as well, but this material was much more difficult for me to film and record.

All this is to say that, in observational documentaries like mine, the choice to focus on particular people in the film, or a particular age group, is primarily a practical one about filming access. I make the filming process appear so easy on the screen, it’s possible to forget the months of work that went into achieving the access, and the practical limitations thereof.

Happily, children can be magnificent subjects for films. The social memes and ideas of the wider world get caught and simplified into their essence by children. This can help make complex subjects more approachable for the audience. In this case, I’m trying to make Afghan society more approachable by seeing it through the eyes of children.

TM: I would imagine that such practical considerations often shape your process. What are other examples of ways in which constraints have yielded gems or welcome surprises in your work?

JL: In 2003, I was in Mahmudiya, Iraq, filming the material that became my short film, Sari’s Mother. It was a project I was working on alongside the subjects that became Iraq in Fragments. We were filming with a farming family south of Baghdad whose child, Sari, had contracted HIV-AIDS through a blood transfusion during the previous Saddam regime. Because of our filming, his case was brought before the deputy health minister—although I think they did little for the family in the end. Our filming was brought to a halt when masked gunmen arrived at the farm one evening and started to motion me into the back of a pickup truck. Fatima, the eponymous mother of Sari, and her oldest daughter, emerged from their house some 50 meters distant and came running toward us across the field. They were calling out to the masked men that I was a “good man” and that they shouldn’t take me. Everyone knew what it meant if they were to have taken me. She was a woman who had emerged from the safety of her home with her daughter to vouch for me, it was a social signal that the masked men were ashamed to defy. I was saved by the bravery of Fatima, but from that day we were to never visit the family at their farm again. We saw them only later, at the hospital in Baghdad. With filming halted, the material we had collected wound up being perfect for a 21-minute short film that fit exactly on a 35mm cinema reel. When I had started filming their story, I had probably imagined the film as something grander in scope, but the film at that shorter length succeeds in a way that I wasn’t expecting. If you watch it, it’s like a feature documentary’s worth of experience and emotion, but in 21 minutes. That’s economy!

TM: You’ve talked about feeling “relieved” about positive feedback from Afghan viewers to Angels Are Made of Light: “Getting it right is a struggle.” Tell us a bit about what you mean. What are some fears/challenges when it comes to getting it wrong? What has been your journey (lessons learned, and how so) over your career—as an outsider, and a Western person, making films in non-Western places?

JL: I have been very pleased by the reaction of Afghans to my film. It’s easy to become buried in the minutia of the filmmaking process and lose track of whether you managed to make something that is true to the subject; and so the positive reaction I have received from Afghans is a welcome affirmation that we succeeded. The fear, of course, is that you might wind up with a film that Afghans don’t like. I mean, if your film is supposed to transmit Afghan reality and Afghan people don’t think you got it right—that means you failed. I am trying to avoid failure and use my powers for good.

With my films I am trying to solve problems of perception. An Afghan documentary filmmaker (and I know a few of them) is more likely to think about the problems internal to their own country, and how to talk about those problems in a film. By contrast, I am not casting a critical eye on Afghan society. I may be physically filming in Afghanistan, but the real problem I am trying to solve is the misconceptions of my intended audience, Americans, about Afghanistan. I consciously work to create a film that will help to fill in those misconceptions with an accurate picture. My goal is to transmit Afghan reality to the non-Afghan viewer, as much as cinematically possible, in two hours. Arguably, I am better equipped to make this kind of film as an outsider who simultaneously knows the American audience like the back of my hand and sees the Afghan subject with the newness of a child.

TM: Have you always been so clear about both your audience and your goals as a filmmaker? Does the process of reaching this clarity vary from film to film, or is it typically there from the inception?

JL: I’m not particular about my actual audience. I am overjoyed to hear that anyone watches my films, whether they are in Iceland or China or wherever. However, I like to imagine an American audience when I’m making films because I have some practical experience with Americans as filmgoers. I worked for a while as a projectionist in my hometown movie theater, and I got into the habit of watching the audiences watch the films I projected. And I watched many films while seated among American audiences. So it must be that I feel the pressure of an imagined American audience—their levels of tolerance, their interests, their cultural knowledge.

In practice, of course, I’m not doing something that is often done: I’m rebuilding a piece of the world using the film medium. I’m not catering to the ordinary documentary film expectations of my imagined American audience, but rather being mindful of their limits. I’m determined to give viewers the “world”—in this case the Kabul neighborhood of Angels Are Made of Light—in as much detail, and on as many different levels, and from as many viewpoints, as I think they can absorb in one film. I don’t want to lose them in the process. I need the audience to assimilate my prototypical Kabul neighborhood in order for it to fulfill its extrapolative function in their imaginations.

TM: It’s clear that documentary filmmaking requires a lot of patience. (Our literary audience appreciates this, given how long it can take to write a book-length work.) You’ve been trying to make a version of Angels since 2007, filming in Iran and Pakistan, for over a year in each case, only to be permanently interrupted by political turmoil. You spent months scouting in Afghanistan, meeting with locals and filming in various sites, before landing at the Daqiqi Balkhi school. I guess my question is: where does that patience and commitment come from? It’s a kind of faith, no?

JL: There is a lot of naiveté that goes into making this kind of film. For one thing it requires a childlike innocence regarding subjects such as financial and retirement planning, and health insurance. You must be ready to pretend that nothing else in the world matters besides making the finest film possible. I have this particular religion, and I take it up anew each time I start a new picture.

TM: Related to that, given your interest in “urgent” subjects—war-torn countries, the West’s involvement/engagement—how do those things go together: urgency and patience?

JL: I feel a sense of urgency to start a film. But once I’m actually looking at the world through my lens, I want to stay that way forever, building a more and more detailed, grand and beautiful cinematic recreation of the subject. Eventually, I run out of money, and that provides the stopping point. If I had unlimited funds, I would not stop filming.

TM: Angels follows three school-age brothers, along with other children, teachers, and administrators, observationally—through a period of three years, when their school in Kabul closed down due to disrepair and they moved to a new school. You recorded 500 hours of picture, and the “text” of the film is made up of unscripted audio interviews—over 8,000 pages of transcript. Talk about patience! Tell us about the editing process, and specifically what was difficult to leave on the cutting floor.

JL: I film observational documentary material in the mode of a storyboard artist laying out scenes. Consequently, it is very easy to edit the material I come back with—at least at the scene level. The first part of editing was simply plowing through scenes: I think with the young Finnish editor, Waltteri Vanhanen, we cut something on the order of 90 or 100 scenes over six or seven months. Then the process became one of arrangement and honing. We had all the scenes on index cards, tacked up to an enormous cork board. For most of the editing, it was going on in the same apartment where I lived. So I would roll out of bed and into the editing suite.

We cut out a lot of good characters whom I liked a lot. In particular there were these two kids who went to the school where we were filming, and they had jobs selling things on the streets of Kabul. So the material following them is really wonderful—all moving camera shots, swooping through the markets. And they were both very sympathetic, interesting characters. Lots of excellent scenes were cut or greatly shortened. But this is the way films get made, I guess.

TM: How do you decide on film format? Iraq in Fragments and Angels Are Made of Light (to the amateur eye) seem to be shot in different formats, and I’m wondering how you negotiate the chicken-and-egg conundrum—discovering/developing the visual language as you go along, and committing to a format.

JL: I want the film to look like I made it in 30 days on a Hollywood backlot with unionized labor. But I have a two-person crew and I’m filming in Afghanistan. So I tend to shoot everything very consistently and I don’t switch the camera in the middle of production. In both Iraq in Fragments and Angels Are Made of Light I used one type of camera/lens the whole way through. In Angels Are Made of Light I even used the same camera to record the 35mm archival material off the flatbed ground glass—so that means the whole film feels like it’s sewn together from one big piece of cloth.

I decided to use 2.39:1 widescreen for Angels for a lot of reasons: I love the way it looks, and because it’s so easy to frame crowd scenes in widescreen. Afghanistan is a country where much activity happens in groups, and so the wide screen actually winds up giving a more precise sense of the group dynamics.

TM: How has the time you’ve spent in Afghanistan influenced/changed your opinions about American policy—or global policies—in Afghanistan? Are there ways in which you hope your films “activate” viewers politically?

JL: I don’t know the answer to Afghanistan’s problems; or even what the United States’ policy should be in Afghanistan. I have my own opinions, but that’s not what I think I can best contribute to the world. Instead, I am trying to give an American audience the foundation of perception and experience through my film that will allow those who view it to imagine Afghanistan and to more accurately calibrate their internal worldview. I focus my films on civilian populations because I think that these are the people who should be foremost in our minds whenever we consider other countries or our own. What will happen to these most vulnerable people if X or Y happens? That’s the question I want to be on the minds of viewers after watching the film. I want my audience to understand the real stakes involved in making decisions in the world, and I want them to see the world as it is. This is the unreachable goal toward which I am working.

TM: The motivation of an “unreachable goal” could be both energizing and depleting. For you it sounds as if it’s mostly a fruitful energy. When/how did you begin to clearly understand that your vocation would orient you toward this unreachability? Or was this something you simply recognized from, say, a young age?

JL: I remember when I was about six or seven my father remarking that “the map is not the territory.” That’s when I understood that it was hopeless. Human beings will never be able to perceive our wider world with true clarity. We’re just not built for it. Nonetheless, it’s a fascinating problem to work on. I get excited just creating these small artifacts, these films, that I think of as little perception capsules. Little time capsules of experience. Like the talking rings of HG Wells’s The Time Machine (1960). Even this activity would be enough to keep me occupied for a lifetime, but I hope to live to see a sea change in the way we think about documentary films; the way they are made, and the way we experience them.

JL: I remember when I was about six or seven my father remarking that “the map is not the territory.” That’s when I understood that it was hopeless. Human beings will never be able to perceive our wider world with true clarity. We’re just not built for it. Nonetheless, it’s a fascinating problem to work on. I get excited just creating these small artifacts, these films, that I think of as little perception capsules. Little time capsules of experience. Like the talking rings of HG Wells’s The Time Machine (1960). Even this activity would be enough to keep me occupied for a lifetime, but I hope to live to see a sea change in the way we think about documentary films; the way they are made, and the way we experience them.

It is enjoyable to think of possible futures of documentary film—new forms that I may yet experience and create—perhaps as something like the artificial reality training modules of The Matrix (1999) or the memory implants of Blade Runner (1982). The function of documentary—at least when I make one—is to augment our vision, understanding, and knowledge of the real world. I look at documentary films in that way—as enhancements, as extensions to human perception. The toolset I use is evolving, but my ultimate goals remain the same.

It is enjoyable to think of possible futures of documentary film—new forms that I may yet experience and create—perhaps as something like the artificial reality training modules of The Matrix (1999) or the memory implants of Blade Runner (1982). The function of documentary—at least when I make one—is to augment our vision, understanding, and knowledge of the real world. I look at documentary films in that way—as enhancements, as extensions to human perception. The toolset I use is evolving, but my ultimate goals remain the same.