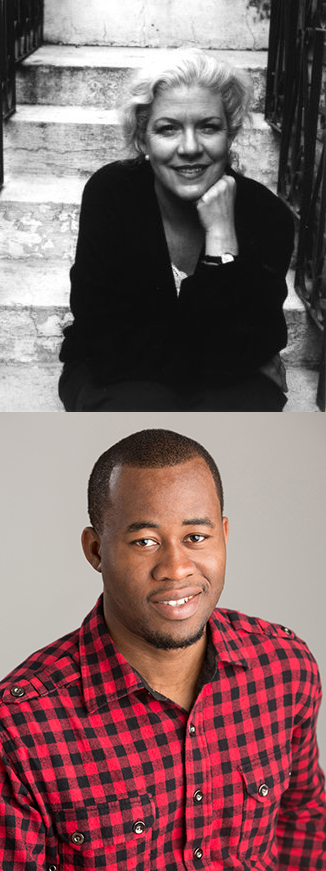

This piece is the first in a series of author interviews about the craft of writing conducted by Chigozie Obioma for The Millions.

Jennifer Clement’s Gun Love is a beautiful novel. The writing is so lovely that, at times, it seems the author is observing the world through a peephole that foregrounds and magnifies every minute object. A tired person is described as being unable to make “my fist,” and a woman’s love interest is described as “the song inside her body.” The characters are eccentric, unforgettable, and nuanced. Pearl, especially, is a wonder: so finely shaped and created.

For the first in a series of interviews focused on the craft of writing, I asked Clement a few questions about her process and technique. If you’ve read Gun Love and have questions for Clement, please post them in the comments section before May 22. We’ll send the first three to the author, making this an ongoing conversation.

Chigozie Obioma: Did you do any research for this novel? I’m curious to know how prior knowledge shaped the lives of the characters in this novel since—as I understand—you have not even been living in the U.S. for a while now.

Jennifer Clement: Yes, I did a lot of research for this novel. I think of some of my books as an iceberg and what the reader reads is the surface of something much deeper. However, the research did not shape my characters. The investigation was into people who live in cars, gun violence, guns, and I did interview survivors of gun massacres. I’m on the advisory board of an organization called SHOT: We the People headed by Kathy Shorr, who photographs survivors of gun shots and how their bodies have been devastated. The truth is I’ve hardly ever lived in the United States. I grew up in Mexico City, where I live today. I lived in New York City from 1978 to 1987. My memoir Widow Basquiat is about this time in New York.

Jennifer Clement: Yes, I did a lot of research for this novel. I think of some of my books as an iceberg and what the reader reads is the surface of something much deeper. However, the research did not shape my characters. The investigation was into people who live in cars, gun violence, guns, and I did interview survivors of gun massacres. I’m on the advisory board of an organization called SHOT: We the People headed by Kathy Shorr, who photographs survivors of gun shots and how their bodies have been devastated. The truth is I’ve hardly ever lived in the United States. I grew up in Mexico City, where I live today. I lived in New York City from 1978 to 1987. My memoir Widow Basquiat is about this time in New York.

Because I live in Mexico, Gun Love is also about how U.S. guns get to Mexico. This has also been a part of my research and the numbers are chilling. As a low count, 20,000 guns cross the border into Mexico every day. There are more than 8,000 gun shops on the U.S. side of the border. This means that both poverty and violence in Mexico and Central America is fueled by U.S. guns.

CO: The characters are eccentric, and this is why they are also so compelling. This, of course, makes them very memorable. Margot, for instance, is able to live in her father’s house for two months with a baby without anyone knowing a child was there. What was the inspiration for such a woman?

JC: I’ve actually read about women who were able to hide their newborn babies for quite some time and I’ve always found this fascinating. It’s not hard to do especially if you’re a lonely girl living in a big house. There is no character in Gun Love who is based on any real person. At a certain point of my writing, I begin to feel a strong tenderness for my characters, which is a kind of love, and then I know the characters have come alive. What you point out reminds me of what Flannery O’Connor said when asked why her characters were so eccentric, “Whenever I’m asked why southern writers particularly have a penchant for writing about freaks, I say it is because we are still able to recognize one.”

CO: For me, this is also in many ways a philosophical novel. There is wisdom, quiet wisdom I’d say, scattered throughout the page in form of aphorisms that Margot passes on to her daughter and therefore the reader (e.g., “If you don’t dream at night then only this life matters.”). Were you thinking specifically in these lines?

JC: I’m glad to hear you think this, as I do also. Part of developing a character is finding out their credo, what they live by. I would never want to write a didactic novel, but a philosophical one, yes. I’m interested in the fact that we spend half our day sleeping in a completely different world. One of my favorite poems is John Donne’s “Elegy X, The Dream” where he says, “If I dream I have you then I have you for all our joys are but fantastical.” I also know it’s in dreams and in the imagination where the muses live.

CO: Again, on a craft level, your language is breathtaking throughout this book. But I also noticed that it seems you save the bulk of the novel’s lyricisms for the end of each chapter. What is important about the end of chapters?

JC: This has to do with my love of poetry. I like to be going someplace and I do see the end of each chapter as a destination, as I do with each stanza of a poem.

CO: The story is extremely conversational in tone. What do you bring to writing dialogue?

JC: When writing dialogue, I think like a playwright. Every conversation has this kind of care. I like to read plays and scripts as a study of craft. This may be the reason that so many of my novels have been staged.

CO: Also, to that question, there seems to be a McCarthyian thrust in your technical attitude towards punctuation, in that you use it sparingly. Thus, much of the dialogue is unmarked while many sentences contain few commas. What’s your rationale for this?

JC: I’ve done this in my last two novels—Prayers for the Stolen and Gun Love. This was deliberate and made me have to be careful so that the reader can easily follow. Since both books are a long monologue, it felt right that the language would appear as a long cascade. I’m an admirer of Cormac McCarthy’s work so, of course, I’ve read him and am interested in what he does with punctuation. The poet W.S. Merwin also experimented with this and eliminated all punctuation.

CO: Imagery is viscerally rendered in most places to such an extent that one begins to almost see oneself living in the filth described, even “breathing in garbage,” as Pearl and her mother do. What is it about poverty that you find compelling?

JC: I don’t think it’s poverty exactly. I am always interested in how language can bring beauty to ugliness and despair. Language can enlighten the divine within the profane. I wanted to do this with gun violence. This was my challenge. In Gun Love, Pearl has empathy for people but also for objects. She discovers this when she senses that the pearls in a necklace are lamenting the sea. This also allowed me to give the guns a voice and history.

CO: It is almost uncanny to say this, but despite the violence and filth, this is a very, very funny book. How do you manage humor in such a dark atmosphere?

JC: Charles Dickens wrote tragedy mixed with comedy and he called this technique, “streaky bacon.” I do the same. I’m from Mexico where we have quite a subversive sense of humor. I think this comes from the fact that if you can laugh at something it doesn’t hurt as much.

CO: Can you talk about the title? There is something mystical yet familiar about the juxtaposition of two words which operationally seem diametrically opposed to each other, and consequentially are light and day. Operationally, “gun” is used to wreak violence often motivated by hate and the consequences are often dark. But “love” operates to bring comfort, consolation, peace, even joy, and consequentially it is always pleasurable. What is the import of the title?

JC: As sometimes happens, the title came to me very early on in the writing of the book and it felt perfect immediately. It has the complexity of describing love for guns but also speaks to a contradiction. The book is about guns, but it also is about the redeeming force of love. I remember Elie Wiesel once said that the people who survived Auschwitz were full of their mother’s love.

CO: In the novel there are different kinds of love—“Sunday love,” “gun love,” “mother love,” etc. Can you speak about your philosophy of love?

JC: Since I see Gun Love as a mixture between a ballad and a blues song, themes of love and music are present throughout the book. One character, Margot, has a philosophy of love, which is based on all the music she’s listened to and calls a “university for love.” At one point she says she has a Ph.D in love at first sight, which I also have!