1.

On a Saturday afternoon in 1983, I picked up Gene Wolfe’s The Shadow of the Torturer in the Fountain Bookshop in Belfast, Northern Ireland. I was 15 years old and a Dungeons & Dragons nerd; I spent a lot of time skulking around the Fantasy and Science Fiction sections of the city’s bookstores. I was drawn to The Shadow of the Torturer by Bruce Pennington’s cover art, which depicted a man in a black cloak striding away from a ruined citadel, a huge sword on his back. The image promised something along the lines of Michael Moorcock’s Eternal Champion Cycle, a baroque, heroic tale with melancholy underpinnings. Promising, too, were the blurbs from Ursula K. Le Guin (“The first volume of a masterpiece.”) and Thomas M. Disch (“Dark, daunting, and thoroughly believable.”). I opened the book and started reading. The first chapter was called “Resurrection and Death.” The first sentence included a word I’d never encountered before: “presentiment.” In the opening scene, some kids were up to no good, trying to get past the locked gate of a cemetery. Sold.

The Shadow of the Torturer concerns an orphan named Severian, who is an apprentice in the guild of torturers—known formally as the Order of the Seekers of Truth and Penitence. The setting is a vast city on Earth (now called Urth) so far in the future that the sun is dying, so far in the future, in fact, that at times it feels like the past. In the world of this novel, science is so advanced that it resembles sorcery. It’s hard to know the mystical from the mechanical. For example, the torturers and other guilds occupy “towers” that the attentive reader realizes before long, are rocket ships. On one level, The Shadow of the Torturer is a fairly conventional bildungsroman. Severian advances from adolescence to early manhood, has his first sexual experience, learns about the complexities of adult life, commits a crime and, by the end of the book, is exiled, setting him on his heroic (or, perhaps, anti-heroic) path.

On another level however, the book is a meditation on the ravages of time, memory, and the ceaseless struggle against extinction and obsolescence. Severian has the gift of total recall. He can remember every moment of his life back to early childhood. At times this seems like a curse. Early in the novel, the torturer’s apprentice is dispatched to the city library and archives with a message for the curator, Master Ultan. Delighted to have his solitude interrupted by a visitor, Ultan prattles on about the vast collection he oversees. Wolfe’s pacing is unhurried. A narrator who remembers everything will give you lots of details:

We have books whose papers are matted of plants from which spring curious alkaloids, so that the reader, in turning their pages, is taken unaware by bizarre fantasies and chimeric dreams. Books whose pages are not paper at all, but delicate wafers of white jade, ivory, and shell; books, too, whose leaves are the desiccated leaves of unknown plants…. There is a cube of crystal here—though I can no longer tell you where—no larger than the ball of your thumb that contains more books than the library itself does.

This last item is typically Wolfean. How can the crystal contain more books than the library, when it is part of the library’s collection? Ultan then goes on to describe the method by which apprentice librarians are selected:

From time to time, however, a librarian remarks a solitary child, still of tender years, who wanders from the children’s room…and at last deserts it entirely. Such a child eventually discovers, on some low but obscure shelf, The Book of Gold….

Then the librarians come—like vampires, some say, but others say like the fairy godparents at a christening. They speak to the child and the child joins them. Henceforth, he is in the library wherever he may be, and soon his parents know him no more.

For the right reader at the right time, The Book of Gold is more than an escape. It is a gateway out of childhood into the adult world and a companion for life. The Book of Gold is malleable; it is a different volume for every reader. I didn’t know it at the time, but on that Saturday afternoon in Belfast, I’d found my Book of Gold in The Shadow of the Torturer and its successors—The Claw of the Conciliator, The Sword of the Lictor, and The Citadel of the Autarch—which together make up a long novel called The Book of the New Sun.

2.

Gene Wolfe died on April 14, Palm Sunday. He was 87. I’m writing this on Easter Sunday, April 21. I was offline most of Holy Week, traveling with my family, and didn’t hear the news of Wolfe’s death until Good Friday. All of this feels uncannily appropriate, a turn of events one might find in a Gene Wolfe novel. As Jeet Heer wrote in The New Republic last week, Wolfe was a writer “with a deeply Catholic imagination.” Born in New York City and raised in Houston, he came to his faith in his mid-20s, after serving as a combat engineer in the Korean War. The experience of the war was traumatizing and left him, in his own words, “a mess.” (In 1991, a small Canadian publisher, U.M. Press, released a volume of Wolfe’s letters to his mother from Korea. They do not make for cheerful reading.) Wolfe converted to Catholicism shortly before his marriage to Rosemary Dietsch, in 1956. He credits her with saving him. As Heer observes, Wolfe, like James Joyce and Flannery O’Connor, wrote analogical fiction that “fused the literal, the metaphoric, and the philosophic into the same narrative.”

Wolfe’s service in Korea was part of the impetus for writing The Book of the New Sun. “I wanted to show a young man approaching war,” Wolfe wrote in the essay “Helioscope.” From his apprentice origins in the citadel, Severian goes on to become an executioner, a soldier, and ultimately a Christ-like savior of the world. Wolfe’s faith informed his decision to make his protagonist a torturer: “It has been remarked thousands of times that Christ died under torture. Many of us have read so often that he was a ‘humble carpenter’ that we feel a little surge of nausea on seeing the words yet again. But no one ever seems to notice that the instruments of torture were wood, nails, and a hammer…. Although Christ was a ‘humble carpenter,’ the only object we are specifically told he made was not a table or a chair but a whip.”

3.

In the autumn of 1984, I sent Wolfe a fan letter. My family had moved from Northern Ireland back to the suburbs of Washington, D.C., where, after three years in Belfast, I had a hard time fitting in among the cliques of the public high school. I was miserable and contemplated suicide. Fortunately, there were a lot of Gene Wolfe books available at the local public library. I read as many of them as I could: The Fifth Head of Cerberus, Gene Wolfe’s Book of Days, The Devil in a Forest, Operation Ares, Peace, and The Island of Doctor Death and Other Stories and Other Stories. The title story of that last volume was a particular favorite. Its adolescent protagonist, Tackman Babcock, lives in a disused resort hotel on a barrier island with his divorced mother and her younger boyfriend, Jason. The atmosphere is Southern Gothic and the setting feels only tenuously connected to reality. (The mother refers to the hotel as the House of 31 February, which tells you everything you need to know.) The reader soon learns that the mother is a drug addict and Jason her supplier. Tackman senses something’s not right, but he’s either unwilling or too young to grapple with it. He copes by reading an adventure story similar to H.G. Wells’s “The Island of Dr. Moreau,” which features a mad scientist, Dr. Death, and his nemesis, the heroic Captain Ransom. The characters and events from the story begin to bleed into Tackman’s life, supplanting his grim reality. It’s a postmodern genre allegory. His mother overdoses but survives. At the hospital, Tackman is told that he will be going into foster care while she recovers. The boy is afraid to finish the book he’s been reading, telling Dr. Death, “I don’t want it to end. You’ll be killed at the end.” To which Dr. Death replies, “But if you start the book again, we’ll all be back.” During that year, I leaned heavily on this idea of reading not as escapist, but as regenerative and sustaining.

In the autumn of 1984, I sent Wolfe a fan letter. My family had moved from Northern Ireland back to the suburbs of Washington, D.C., where, after three years in Belfast, I had a hard time fitting in among the cliques of the public high school. I was miserable and contemplated suicide. Fortunately, there were a lot of Gene Wolfe books available at the local public library. I read as many of them as I could: The Fifth Head of Cerberus, Gene Wolfe’s Book of Days, The Devil in a Forest, Operation Ares, Peace, and The Island of Doctor Death and Other Stories and Other Stories. The title story of that last volume was a particular favorite. Its adolescent protagonist, Tackman Babcock, lives in a disused resort hotel on a barrier island with his divorced mother and her younger boyfriend, Jason. The atmosphere is Southern Gothic and the setting feels only tenuously connected to reality. (The mother refers to the hotel as the House of 31 February, which tells you everything you need to know.) The reader soon learns that the mother is a drug addict and Jason her supplier. Tackman senses something’s not right, but he’s either unwilling or too young to grapple with it. He copes by reading an adventure story similar to H.G. Wells’s “The Island of Dr. Moreau,” which features a mad scientist, Dr. Death, and his nemesis, the heroic Captain Ransom. The characters and events from the story begin to bleed into Tackman’s life, supplanting his grim reality. It’s a postmodern genre allegory. His mother overdoses but survives. At the hospital, Tackman is told that he will be going into foster care while she recovers. The boy is afraid to finish the book he’s been reading, telling Dr. Death, “I don’t want it to end. You’ll be killed at the end.” To which Dr. Death replies, “But if you start the book again, we’ll all be back.” During that year, I leaned heavily on this idea of reading not as escapist, but as regenerative and sustaining.

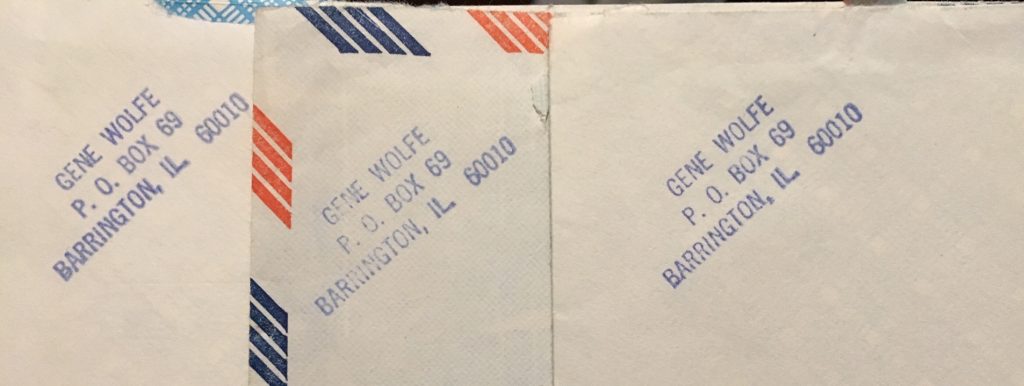

A week before Christmas, a padded envelope arrived in the mail for me. Inside, there was a book-shaped object in wrapping paper, with a label reading: DO NOT OPEN BEFORE CHRISTMAS OR YOU WILL BE CROTTLED BY GREEPS. FIAT! FIAT! FIAT! There could be only one person who would write such a label, but I obeyed the directive and didn’t open it until Christmas Day. Gene Wolfe had sent me a copy of Universe 7, an anthology featuring stories by Fritz Leiber, Brian W. Aldiss, and himself. On the title page of Wolfe’s story, “The Marvelous Brass Chessplaying Automaton,” he had written in blue ink, “For Jon Michaud” and signed his name. It was the greatest gift of my short life.

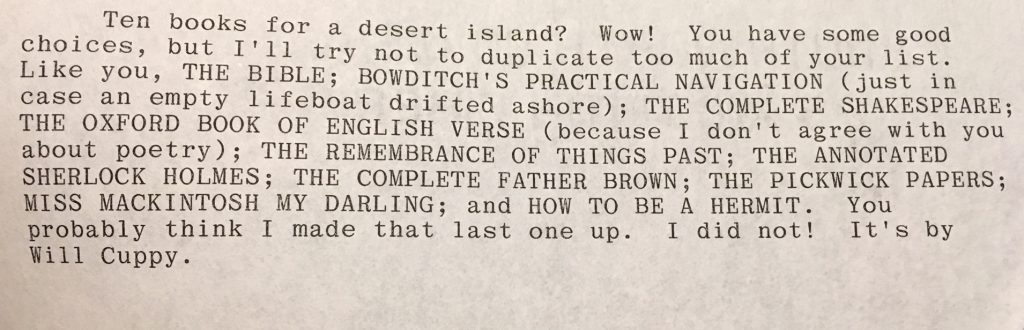

With that, I began a correspondence with Wolfe that lasted about two years. He was kind and generous and patient and encouraging. He answered my questions about his books, and offered reader’s advisory services, directing me to the seminal Harlan Ellison-edited anthologies Dangerous Visions and Again Dangerous Visions as well as the work of an up-and-coming writer named Nancy Kress. I asked him for his 10 desert-island books and his answer was an index of his influences: The Bible, Shakespeare, Remembrance of Things Past, The Pickwick Papers, and The Complete Father Brown. (He also included a practical volume, How to Be a Hermit by Will Cuppy.)

With that, I began a correspondence with Wolfe that lasted about two years. He was kind and generous and patient and encouraging. He answered my questions about his books, and offered reader’s advisory services, directing me to the seminal Harlan Ellison-edited anthologies Dangerous Visions and Again Dangerous Visions as well as the work of an up-and-coming writer named Nancy Kress. I asked him for his 10 desert-island books and his answer was an index of his influences: The Bible, Shakespeare, Remembrance of Things Past, The Pickwick Papers, and The Complete Father Brown. (He also included a practical volume, How to Be a Hermit by Will Cuppy.)

Along the way, Wolfe taught me what it took to be a writer. Here he was, the winner of the Nebula, and World Fantasy Awards, and he still worked a full-time job as an editor at the trade journal Plant Engineering. Wolfe did his writing early in the morning, before going to the office. He wrote at least five drafts of his books, a number that was daunting for a teenager who had trouble finishing first drafts. At one point he noted that his latest book was on hold while he did his taxes. Wolfe was a devoted husband and a father of four children. His example was a welcome counter to the romanticized notion of the philandering rebel artist. Regular habits, a strong work ethic, and a love of revision were the secret ingredients to a successful writing career.

Along the way, Wolfe taught me what it took to be a writer. Here he was, the winner of the Nebula, and World Fantasy Awards, and he still worked a full-time job as an editor at the trade journal Plant Engineering. Wolfe did his writing early in the morning, before going to the office. He wrote at least five drafts of his books, a number that was daunting for a teenager who had trouble finishing first drafts. At one point he noted that his latest book was on hold while he did his taxes. Wolfe was a devoted husband and a father of four children. His example was a welcome counter to the romanticized notion of the philandering rebel artist. Regular habits, a strong work ethic, and a love of revision were the secret ingredients to a successful writing career.

When an English teacher at my high school refused to let me write a term paper about Wolfe’s books because he wasn’t “well known” enough, Wolfe sent the man a letter, listing his awards and prizes. “But judging a novelist by his credentials is like judging a racehorse by its bloodlines; performance is what matters,” he wrote. He included paperback copies of The Shadow of the Torturer and Peace for the teacher to read. By that time, though, I’d graduated from high school and was on my way back to Northern Ireland. Wolfe’s books and letters, his kindness, had carried me through a very difficult time in my life.

4.

Wolfe published more than 30 novels and a dozen collections of short stories in his long career. Eventually, he was able to give up his day job and write full time. His oeuvre is uneven. Though I own a signed, limited edition of Free Live Free, the novel he published after The Book of the New Sun, I’ve never been able to finish it. The arch cleverness of some of his other works has, at times, left me cold. But those examples are the minority. Wolfe memorably explored ancient Greece in The Soldier Trilogy, and he returned to the universe of The Book of the New Sun in The Urth of the New Sun and two successive sequel cycles, which are complex and rewarding extensions to his masterpiece. (And it should also be said that Wolfe remains a chronically underappreciated practitioner of the short story.) His influence can be seen widely. Neil Gaiman has been vocal about his admiration for Wolfe, calling him “possibly the finest living American writer.” Perhaps there would have been no Game of Thrones without Wolfe’s Urth as an antecedent. “I learned so much from Gene,” George R.R. Martin wrote last week. To my mind, the Citadel, where Samwell Tarly goes to learn to be a maester, is an homage to Master Ultan’s library in The Shadow of the Torturer.

Wolfe published more than 30 novels and a dozen collections of short stories in his long career. Eventually, he was able to give up his day job and write full time. His oeuvre is uneven. Though I own a signed, limited edition of Free Live Free, the novel he published after The Book of the New Sun, I’ve never been able to finish it. The arch cleverness of some of his other works has, at times, left me cold. But those examples are the minority. Wolfe memorably explored ancient Greece in The Soldier Trilogy, and he returned to the universe of The Book of the New Sun in The Urth of the New Sun and two successive sequel cycles, which are complex and rewarding extensions to his masterpiece. (And it should also be said that Wolfe remains a chronically underappreciated practitioner of the short story.) His influence can be seen widely. Neil Gaiman has been vocal about his admiration for Wolfe, calling him “possibly the finest living American writer.” Perhaps there would have been no Game of Thrones without Wolfe’s Urth as an antecedent. “I learned so much from Gene,” George R.R. Martin wrote last week. To my mind, the Citadel, where Samwell Tarly goes to learn to be a maester, is an homage to Master Ultan’s library in The Shadow of the Torturer.

Remember what Ultan said about the child who discovers The Book of Gold? “Henceforth, he is in the library wherever he may be, and soon his parents know him no more.” That was true for me. I went on to become a librarian. About a decade into my library career, I wound up working in the archives of The New Yorker. One day, going through a card catalog of the magazine’s contributors, I came across Wolfe’s name. He’d published a single story in the magazine, “On the Train,” in April of 1983, which would have been right around the time I picked up The Shadow of the Torturer in the Fountain Bookshop.

I made a photocopy of the card and mailed it to Wolfe. It had been more than a dozen years since we’d corresponded and I allowed in my letter that he might not remember me. A week later came the reply. “Of course I remember you,” he wrote. And then he offered to read and critique whatever I was working on. He was there all along. And now he’s not.