His voice came to me right before the world began to end. It was a cold evening in October of 2016—slate grey skies, the highway flat, that Sunday feeling where the worries of the week ahead overtake the pleasure of a weekend away. Leonard Cohen on the stereo, speaking more than singing. He put all casual conversation to an abrupt end.

That wasn’t the first time I heard Cohen. I knew his best-known songs, what his voice sounded like. But it was the first night I really heard him, the first night his voice reached inside and gutted me. It always seems so strange and stupid, in retrospect, when something precious is handed to you, and years go by before you accept it and give thanks for the gift. Until then, I simply hadn’t been paying attention.

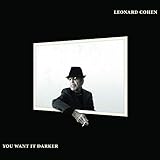

On November 7, 2016, after releasing You Want It Darker, his 14th album, Cohen died at the age of 82. One day later, Donald Trump was elected President.

On November 7, 2016, after releasing You Want It Darker, his 14th album, Cohen died at the age of 82. One day later, Donald Trump was elected President.

My introduction to Cohen’s extensive catalogue triggered a chain of events, one that continued long after the think pieces were published, after a new terror took root, after Cohen’s wiser, long-term fans quietly went about the lonely work of mourning their warrior poet king. I found myself enthralled, delighted, heartbroken, ecstatic, in the midst of that otherworldly experience people so rarely speak of. It’s a sensation that tends to be relegated to the discovery of a band or writer as a teenager, when emotions are so high that the sounds and stories you connect to become woven into the very fiber of the person you become. In the two years that have passed since that night in the car, listening to Cohen’s songs, reading his lyrics and poetry, I have reconnected with a part of myself I’d been trying to shut off since I was 14 years old. I was awkward, obviously; a weirdo, definitely. In those ways I was no different than most of my peers. What caused me trouble was my obsession with death.

I’m not sure what came first—the depressing music, an all-black wardrobe, or Emily Dickinson. At 14, it was important to constantly display signifiers of what I was interested in, and I did what I could to dress like a reclusive genius who entertained no visitors and lived entirely in her head. I placed a dog-eared copy of Dickinson’s poetry on the lunch table next to my sandwich, hoping someone, anyone, would try to talk to me about it. I admired Dickinson’s origin story as much as I did her writing. Her subject matter and prolific creativity were mystical, so I grouped her with the other wise, witchy, artistic women I idolized: Tori Amos, Francesca Lia Block, Winona Ryder. The fact that Dickinson was a loner who died unmarried, that no one knew her depths until after she was gone, made her brilliance that much more powerful to me.

When I read “Because I could not stop for Death,” one of her most famous poems about the afterlife, I marveled at how Dickinson cleverly personified Death. Her Grim Reaper was not a frightening phantom, come to steal her away. Instead, he was a courteous gentleman who took her on a drive. Dickinson notes his civility—could he have been flirty, even, to the poem’s narrator, who was dressed for the journey in gossamer and tulle? In this poem, Death offers the promise of immortality. But Dickinson suggests her narrator had an independent streak, one that compelled her to make her own decisions and choices, not only about her death, but also about her life. This set my teenage mind on fire: The thought that death itself could be confronted like any other person, that it was both far away and yet just beyond an invisible veil that could, at any moment, be lifted. These themes are repeated again in Dickinson’s captivating, metaphor-rich “Death is a dialogue,” which opens up a conversation between Death and a Spirit, in which they argue about the finality of consciousness.

Do we return to the earth as dust, or is the body just one aspect of a human being? I didn’t know. But, man, in the throes of adolescence, it felt so good to ask, to question, and not in terms of religion or faith. Dickinson’s verses were a constant source of comfort. Heaven, hell, death, god, eternity—she covered it all, simply, perfectly, in a way that actually made sense. The more I obsessed about death, the more fascinated I was. But I soon realized it was best to keep my thoughts about the eternal mystery to myself. If I did express them, I was pandered to or deemed unnecessarily negative, morbid, a freak. I didn’t understand why our culture so readily assumed that thinking about death was gauche, inappropriate, or, more broadly, a red flag, something to keep an eye on, to worry about. Nobody could answer this in a way that satisfied me, and so I returned to the books—the novels and poems that some called melancholy or sinister, but that I needed as a guide, a way of coming to terms, in my own small way, with why we are here and where we might go.

As the years passed, I thought I became less afraid, more confident in what would always be unknowable. Goth culture never quite went away, but I stopped devoting so much time to worship at that particular altar—though I kept wearing black, because what New Yorker doesn’t? I kept the music, too, and continued reading the goths whose merit nobody would dare question: the Brontës, Daphne du Maurier, Poe. My taste hadn’t changed, but I figured I was growing up, growing out of it, whatever it was. I assumed, like so many mansplaining men had told me, that I should smile more.

And so it went, until my rediscovery of Cohen, which set in motion a new cycle of questions about death and the soul. My mother became seriously ill. As I watched her health decline, I became gripped by a fear of time. Not only my own time with her, or the time she had left, but the vast, cavernous depths of what that meant. The weeks that slipped by were not as productive as I wanted them to be, not as generous, not as articulate. There were words I could no longer say. The words I did say so many times—I love you, I love you—seemed to have lost their meaning entirely. I reckoned with deep regrets, with daily disappointments, with the endless, hopeless wishing that I could live in the past, when so much was still possible even if it was cloaked in shadow. Back then, the future was a fantasy, even if it was a dark one. Back then, I considered my research, the books, the songs, all part of a very interesting experiment. By the end of that experiment, I told myself, I’d be adequately prepared for grief, in whatever form it came. I thought that being interested in death meant, on some level, that it couldn’t hurt me as much as it did someone else.

Cohen and Dickinson both have an immortal quality, and both treat death as a muse. This past November, FSG published The Flame: Poems Notebooks Lyrics Drawings, Leonard Cohen’s posthumous diary, a collection he vowed to complete before he died in late 2016. The book is a beautiful, intimate look at his life and work, combining his poetry, notebook entries, and lyrics, interspersed with drawings and self-portraits. In “I Pray for Courage,” Cohen writes:

Cohen and Dickinson both have an immortal quality, and both treat death as a muse. This past November, FSG published The Flame: Poems Notebooks Lyrics Drawings, Leonard Cohen’s posthumous diary, a collection he vowed to complete before he died in late 2016. The book is a beautiful, intimate look at his life and work, combining his poetry, notebook entries, and lyrics, interspersed with drawings and self-portraits. In “I Pray for Courage,” Cohen writes:

I pray for courage

Now I’m old

To greet the sickness

And the cold

I pray for courage

In the night

To bear the burden

Make it light

I pray for courage

In the time

When suffering comes and

Starts to climb

I pray for courage

At the end

To see death coming

As a friend

In these verses, I feel such compassion and empathy for the burdens of life. Cohen describes a sleepless night wondering, fearing, suffering, while praying for courage, for the rosy fingers of dawn, and for a way to lighten his emotional load. And he prays to see death arriving as a friend, an ally, similar to the way Dickinson describes her supernatural carriage ride. Then, in “School Days,” Cohen personifies time, just as he and Dickinson personify Death.

I never think about The Past

but sometimes

The Past thinks about me

and sits down

ever so lightly on my face—

Here, the Past is a being, someone capable of thought—and someone who Cohen can’t escape. He claims not to think about it, but the Past thinks about him, taunts him a bit, takes him to places in his mind he might prefer to avoid. This is what the pre-grief I live with feels like, the sense that I’m constantly readying myself, waiting for the worst to happen, a phone call in the middle of the night, an accident, or worse, the slow onslaught of the inevitable, bringing with it the small, unavoidable heartaches that pile upon one another until, yet again, I find myself daydreaming about the last terrible piece of news as if it were a friend, a Past like the being in Cohen’s poem, better and more comforting in its known-ness than the confusion of the present, a new shape of pain.

It’s in poems like these that I find solace—solace in who I was, who I am, and who I hope to be. I still wear black, though not exclusively. I still love sad songs, sad books, stories that end not with everything wrapped in a bow, but with some sense of lament, a nod to the human folly, flaws, and inconsistencies that make even a “happy ending” feel like a question mark. This is what Cohen has taught me, in his songs and his poems, and what Dickinson knew before he did. Both writers invite us into their inner lives because they take their inner lives seriously. They take these questions without answers seriously. They never make light, they never turn their heads away, they refuse to change the subject. They look at the inevitable and perhaps they are scared—and I am, too. But their words are like a hand grabbing mine tightly. They are a reason to keep moving forward.

Reading Cohen’s final poems and absorbing his drawings and lyrics, then reading Emily Dickinson’s verses again and again, I’m reminded of how far I’ve come through the darkness. To some, my current state of mind may seem like something to escape—and so it was to me, even when I knew that the darkness could be a friend, a feeling, a weight, not oppressive but thoughtful, not excruciating but auspicious. Now I move through the darkness, and I try to find peace in what I can’t see. Once, I anticipated what would happen and thought I could prepare. Now that saying goodbye is no longer a vague concept but a heavy reality, my poets sit with me. They remind me that I will never be ready. Not for death, not for the sorrow that haunts my days, not even for the happiness that arrives with a shock. But they also tell me I shouldn’t give up trying.

Image Credit: Unsplash/Cherry Laithang.