“America I am unnameable.” Several poems in Shane McCrae’s new book, The Gilded Auction Block, begin with America: the idea, the myth, the collective body. The speakers of his poems are nearly ecstatic with frustration: tired and terrified, they are convinced “America you wouldn’t pardon me.”

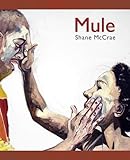

Shane McCrae has many gifts as a poet, but among his most hypnotizing is his ability to create poems that simultaneously blare and beacon. Since his first book, Mule, in 2011, McCrae has been creating ambitious work that demands—earns—our attention. I often feel out of time when I am reading his words; they arrive with a Miltonic fury, and yet they are so contemporary and critical for our present, strange world.

We spoke about our current political fever, Hell, and how poems sometimes have to wait for the right moment to arrive.

The Millions: I don’t know if there’s an ideal way to read a particular book of poetry, but I read The Gilded Auction Block after midnight, at my desk, in what seemed like phosphorescent light. I had the feeling of being consumed by the book—particularly “The Hell Poem”—and each time I turned back to the cover, Ulisse Aldrovandi’s monstrous image unnerved me further. It’s rare to experience a book that hits so hard on the levels of form and function and feeling, which leads me to wonder: How did this book come together for you? How did you go about structuring, ordering, arranging these pieces into their profluent whole?

Shane McCrae: Thank you so much for the kind words about the book. Well, “The Hell Poem” came first. In 2014, I got it into my head that I wanted to write a Dante-esque, Inferno-ish poem, which is a terrible thing to get into one’s head—although there is something to be said for going into the writing of a poem knowing it will be impossible for the end result to be anywhere near as good as its inspiration. So I wrote a few sections of “The Hell Poem,” got stuck, and then abandoned the poem. Not long after that, I wrote In the Language of My Captor. Then Trump was elected. And immediately I felt I had to write something in response to Trump’s election, and wrote “We’ll Go No More a Roving.” Maybe a month or so after that, I wrote “Everything I Know About Blackness I Learned from Donald Trump,” and poems along the lines of that poem followed. Eventually, I started thinking about “The Hell Poem” again, and realized there was a place for Trump in it—indeed, I think the reason I had gotten stuck was that the poem was waiting for Trump.

TM: In other interviews, you’ve spoken with illuminating complexity about confessional poetry, noting that “in some very actual ways the confessional mode, strictly speaking, is not possible for non-write writers” because the confessional condition “assumes a fall from grace, but only whites occupy the initial position vis-à-vis grace from which the confessional poet must fall.” Yet you’ve also described a simultaneous pull toward that space of confession in verse, and I think one of the many powerful modes of The Gilded Auction Block is that the book feels kenotic (both metaphorically and theologically)—an emptying on the way toward reception. Was there a kenotic sense for you in writing these poems—and if so, what has been emptied, and what might be received?

SM: Oh, I wouldn’t describe anything I’ve ever done as kenotic, not thoroughly—kenosis is something I think one works toward one’s entire life. But I also think I never manage to really empty myself when writing my autobiographical poems—that’s why I keep returning to certain figures, particularly my grandmother. I don’t ever—not that I can recall at the moment—feel satisfied by the writing of my more autobiographical poems. I can manage to get my non-autobiographical poems to seem finished to me, but my autobiographical poems always seem not quite right. They are the poems I consistently abandon.

TM: Your previous book, In the Language of My Captor, begins with the poem “His God,” which includes the lines “his / God is a stranger // from no country he has seen.” The Gilded Auction Block begins with “The President Visits the Storm,” which includes a clever allusion to Mary’s Assumption and an ominous nod toward the Book of Revelation—both skillful touches that feel like transfigurations. I enter both books thinking about forms disembodied, and looking for the places of souls. Considering this book is peppered with quotations and permutations of Donald Trump, how have these past years had you thinking about bodies?

SM: Well now I simply do not have a good answer for this—not yet. Let’s see. The reason I initially felt like I didn’t, and wouldn’t, have a good answer for this question was that I don’t really sit around thinking about bodies—I don’t often think about the things it seems smart people think about. But I do think about the bodies of poems sometimes, and I have lately become intrigued by what seem to me to be the contradictory dominant impulses behind the forms of the poems of younger poets writing today—an impulse to expand, and an impulse to compress. Often one will see poems that open up a lot of space inside themselves by expanding across and down the page. But one also sees a lot of prose poems, which, even though they are written from margin to margin, seem very compressed to me—they’re very dense. And I think each of these impulses has to do with the ear rather than the eye. Each, I think, responds to a desire to make the music in poems more apparent than it would otherwise be—or, at least, to make the poet’s attitude toward music more apparent. The spread-out poem isn’t so certain readers will notice its music; the prose poem is more trustful. But I think the popularity of the prose poem is a holdover from life before Trump. Who feels confident their body will be recognized and acknowledged for what it is nowadays?

TM: We’re both editors for Image Journal, a magazine that publishes writing “informed by or grappling with religious faith.” One of your own poems for the magazine that appeared a few years ago ends with the lines “Lord forgive my torturers // Who hate my faults as if my faults were theirs.” It makes me think of something you said upon publication of your first book, Mule, quipping “I wrote a bunch of poems about God.” I’m drawn to ambitious writers like yourself and Katie Ford, whose religious and theological grappling has a rich poetic lineage. What draws you toward God—in poetry, and in life? Who are poets of doubt and faith whose work has influenced or interested you?

SM: I believe God is; I have no doubts about the existence of God. And I think it’s God’s very being that draws me toward God. If one believes God is, how can one be otherwise but drawn toward God? That said, I find the mystery(ies) of God overpoweringly attractive—when thinking about God, one inhabits a space in which one can think forever. That’s nice. And with regard to thinking, I suspect I’ve been most profoundly influenced and interested by Jorie Graham and Susan Howe—both of them say deeply true things about how the mind works. As for poems that have more explicitly to do with God, I think I’ve been most influenced and interested by George Herbert.

TM: “And even in my dreams I’m in your dreams” ends one of your poems in this new book—a work, like several others, that includes Trumpian excerpts and exhortations. Your book feels like a lament for our age, or perhaps a catalog of spiritual exhaustion: “America I was driving when I heard you / Had died I swerved into a ditch and wept.” How does it feel to have a book publish now, when the murmurs of a coming election are nearing a crescendo? What might the place of poetry be in a world so full of noise?

SM: I think noise requires poetry, because I think poetry requires a retreat from noise. Although, you know, it’s a book of poetry, and so is unlikely to have a huge reach. I hope nonetheless that The Gilded Auction Block might make some positive contribution to the discourses about Trump and about America. When FSG took the book, there was some feeling that it needed to be published as quickly as possible—both because it was maybe timely, and because, at the time, it was thought that Trump’s presidency might be brief. I feel as if every moment of every day I am actively wishing Trump weren’t president; since he is president, I hope my book, in its small way, can work against him.

TM: I’ve already mentioned “The Hell Poem,” the masterful, long poem that anchors The Gilded Auction Block, but wanted to speak about it more. I’ve read other poets who are transformational with language—giving us new ways to see—but you also have a transfigurative sense, of creating, like Dante and Milton, a surreal world in a poem that still feels grounded in earthly suffering. I’m even reminded of Flaubert’s The Temptation of Saint Anthony; I feel out-of-this-world, and yet reminded of my form: “At that a darkness like the darkness / Before the world was overtook me.” What route led you toward this Hell poem? What caused this poetic descent?

SM: Folly. Folly got me going, and folly kept me going. The poem came out of nowhere, and in retrospect I think if I had planned it out a little I could have saved myself a lot of work. After I got stuck writing “The Hell Poem” (as I mentioned above), I decided that I had gotten stuck because I didn’t want to write anybody into Hell. And the obvious—to me, at least—solution was to write a poem set in Purgatory instead. So I wrote a considerably longer poem set in Purgatory which I now think was a near-total failure. I say “near-total,” because I did manage to salvage a bit of it and plug that into “The Hell Poem.” But it wasn’t until I had written 60 pages of that Purgatory poem that I realized it was a failure. That failure aside, however, once I was a few sections deep in “The Hell Poem,” I asked Christine Sajecki, with whom I had worked previously, if she would be willing to make some paintings for it, and I still can’t believe she said yes. The paintings she made are wonderful. At bottom, I think I’ve always wanted to say something worthwhile about the world and the people in it, and the ascendance of Trump, because he is a caricature and makes all around him caricature, made the effort to say something a little easier. But, really, I’m still trying.