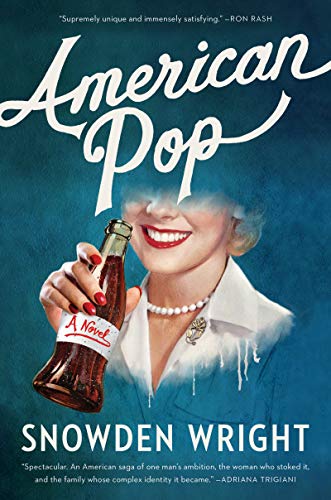

On Feb. 5, William Morrow will release Snowden Wright’s second novel, American Pop. Early reviewers have called it “supremely entertaining,” “not only excellent Southern Gothic fun but a panoramic tour of the American Century.” Snowden and I were college roommates, where we dreamed of one day becoming novelists and then manufacturing a public feud to help drum up book sales. We talk pretty much every day, about nothing and everything, but we have never been as formal as we are in this interview:

The Millions: So, what’s the book about?

Snowden Wright: I’ve always enjoyed describing American Pop with a hypothetical question: What would a novel about the Kennedys be like if they’d made their fortune by inventing Coca-Cola? Of course, the imprecision of that question often leads people to ask, “So it’s about the Kennedys?” and I have to say, “Well, uh, no.” Then they ask, “But it’s about Coca-Cola, though?” and, breaking out in a sweat and wrenching an imaginary necktie, I say, “Not exactly.”

More precisely, then: American Pop is a multi-generational saga about a family that owns a soft-drink company named PanCola. The novel follows the Forster family through more than 1000 years of American cultural history. It uses techniques of historical reportage to depict the Forsters’ personal lives, showing how, in Nathaniel Hawthorne’s words, “families are always rising and falling in America.”

In an article on Coca-Cola for a trade publication, a journalist once wrote, “Why read fiction? Why go to movies? The soft drink industry has enough roller coaster plot-dips to make novelists drool.” My immediate thought after reading that was, “Challenge accepted.” American Pop is the result.

TM: Where did the original idea for the novel come from?

SW: My first novel, Play Pretty Blues, is primarily set in the 1920s, focused primarily on one central character, and takes place primarily in Mississippi. With American Pop I wanted to do more. I wanted it to span a longer period of time. I wanted it to explore more characters. I wanted it to have a broader setting and scope. Why not, I thought, take on the incredibly easy task of writing a novel that encapsulates a century of culture, popular and personal, in America?

I honestly can’t remember whether that ambition came before or after the peg on which to hang it. Soda has always seemed to me such an American drink. It is to this country what wine is to France, tea to England, beer to Germany, or toilet water to misbehaving dogs. Soda is especially pervasive in the South, where I’m from and the region I love exploring, scrutinizing, praising, and criticizing in my work. As Nancy Lemann wrote in the sublime Lives of the Saints, “Southerners need carbonation.” Soda, I figured, would enable me to wed the national and the regional, America and the South, and examine the relationship between them.

TM: Can you elaborate a little on that? What makes a Southern story Southern, both in fiction and on a porch in the middle of a day? Is it a genre, with certain characteristics?

SW: Southern stories require at least one dog, but it does not have to have four legs. Southern stories know how to whistle but not necessarily “Dixie.” Southern stories are never served without a cocktail napkin, must own at least two pairs of duck boots, and always remember to return the casserole dish.

Honestly, though, what makes a story Southern, in my experience, is that it’s a story. That’s the only criterion. I grew up in a family of regalers, the type of people who love when a new girlfriend or boyfriend visits over the holidays because it allows us to repeat the same nuggets, buffed to a high shine, of family lore. And they are, in fact, typically told on a porch.

If I had to give a response that’s a bit less of a tautology, I’d say that Southern stories tend to involve a reckoning with the past, give a strong sense of place, feature colorful characters, and try, first and foremost, to entertain the reader. There are many Southern writers out there, myself included, who appreciate tightly constructed sentences and beautiful language, but I’d argue there are many more Southern writers, myself also included, who appreciate an engaging narrative most of all. The art of storytelling, I always try to remember, is just that: an art. Writers should give it as much of their attention as they do the more seemingly highbrow aspects of their craft.

TM: I want to force you to get a little more specific on this, so I’m going to follow up with a two-part question. Part one: What’s your Mount Rushmore of Southern fiction?

SW: George Washington, respected, somber, and not, in fact, wood-toothed, would be Faulkner‘s Absalom! Absalom! Thomas Jefferson, renaissance man about town, would be O’Connor‘s Complete Stories. Teddy Roosevelt, that quotable rapscallion, would be Hannah‘s Ray. And Abraham Lincoln, emancipator and proclaimer, would be Morrison‘s Beloved.

TM: And part two: Do you see those books having anything in common?

SW: The past’s persistent intrusion into the present. From Ray Forrest confusing memories of his time in Vietnam with those of Jeb Stuart‘s Civil War campaigns, to the spiteful haunting of 124 by what won’t stay buried, to Quentin Compson yelling, “I don’t hate it! I don’t hate it!” after recounting the story of Thomas Sutpen, the past, in all four of those books, refuses to stay put.

Think of Faulkner’s most frequently quoted line, “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” I’ve seen that used as an epigraph for probably a dozen books—Ace Atkins‘s White Shadow, Willie Morris‘s North Toward Home, and Tiffany Quay Tyson‘s The Past Is Never come to mind—and most of them, from what I recall, are by Southern writers. Why? The line is universally applicable. It’s the O negative of epigraphs.

TM: I suppose, yes, the line is universally applicable, but it seems particularly so in Southern fiction. Can you talk about why? And perhaps how American Pop wrestles with that?

SW: Freshman year of college, I had two roommates, one from New Jersey and one from Maine. They used to joke about how nervous they’d gotten when they found out they would be living with some guy from Mississippi who lived on Confederate Drive. That really was the name of the street I lived on.

I don’t blame them for having been nervous. The South has, to put it lightly, a fraught past, with slavery and the Civil War and, more recently, racism, misogyny, homophobia, and anti-intellectualism. We have a perpetual BOGO sale on social issues. In American Pop, I tried to grapple with those issues, not only as they relate to the South, but also as they relate to the country as a whole. There’s a reason I didn’t title the novel Southern Pop. The South’s problems are also America’s problems, and that’s never been clearer than it is in our current political situation.

TM: I’m glad we’ve finally gotten around to the issue of race. As a Northerner myself, as an outsider, when I think of the South I automatically think of the legacy of slavery, and the way it seems to permeate every aspect of Southern culture, from the food to the music to the laws. You’re publishing a novel in 2019 about a rich white family in Mississippi. How does this book grapple with the legacy of slavery?SW: With empathy and honesty, I hope. Although the main family in the novel is white, I made a point of including many characters of color, characters who are also not defined solely by their race. Sometimes I tried to address racism overtly, such as a chapter in which wealthy Mississippi farmers brazenly discuss how to disenfranchise black voters, and sometimes I tried to address racism more subtly, such as a chapter that involves Josephine Baker, a black woman who enjoyed immense success after she left America for the more racially tolerant France. The key, I think, to addressing any social issue, be it race or sexism, homophobia or nationalism, is to keep it character-based. Make the issue universal by making it personal. Don’t stand on a soapbox. Stand in someone else’s shoes. Stand in the characters’ shoes. Let the reader feel what they feel.

TM: Empathy’s such a tricky concept. A friend of mine, James Dawes, recently published a brilliant book, The Novel of Human Rights, in which he argues that exercising so-called empathy is not only performative but potentially destructive, but then Obama says we need to cultivate more of it. I don’t know. When people ask me questions like the ones I’m asking you, I feel ill-equipped to answer them. That’s why I write fiction. For the most part, I think novels are probably more articulate than novelists—and yet here we are, in an author interview, a genre I legitimately love. The first thing I bought after selling my first novel was a collection of out-of-print Paris Review interviews. Do you read a lot of these things? What do you get out of them?

SW: The first thing I bought after selling my first book was The Clapper, which ever since I was a kid I considered the peak of luxury. Fancy people don’t even have to get up to turn out the light! I could not get it to work. Maybe I clap weird.

Which is to say, yes, absolutely, I love author interviews. Even though I agree that novels are more articulate than novelists—lovely way of putting it, by the way—interviews not only humanize authors (“Her French bulldog has the same name as mine!” “He can’t afford anything nicer than Bustillo either!”), making a writing career feel attainable, but they also, oftentimes, provide a unique, insider perspective on craft. You get a sense of writing as a job. To hear an author recount how agonizing a copyedit was makes you realize writing takes work. It also makes you realize writing is work.

I’m especially fond of hearing bits of trivia. Alternate titles. Hidden allusions. Want to hear one from me? Every novel I’ve written, published or drawer-filler, has included an indirect reference to the movie Die Hard.

TM: I recently found out that a friend of mine used to work in the actual Nakatomi Plaza, and it blew my mind. While we’re here, talking about craft and being meta about author interviews in general, can you talk about your decision regarding the metatextual elements of American Pop, the ways in which the book seems narrated by a real-life scholar of this fictional cola company?

SW: My first conception of the book was for it to be the opposite of Capote‘s “nonfiction novel” In Cold Blood. I wanted American Pop to be fictional nonfiction. To achieve that effect, I used certain techniques of nonfiction, such as source citations, quotes from interviews, and the use of specific dates and times, similar to what Michael Chabon did in The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Klay and Susanna Clarke in Jonathan Strange & Mr. Norrell.

Aside from the playfulness that allowed me—I get an absurd thrill out of making readers wonder if a metatextual source is real or made-up—it also allowed me, I hope, to create a greater sense of verisimilitude, to heighten the readers’ suspension of disbelief, to make them feel that this really happened.