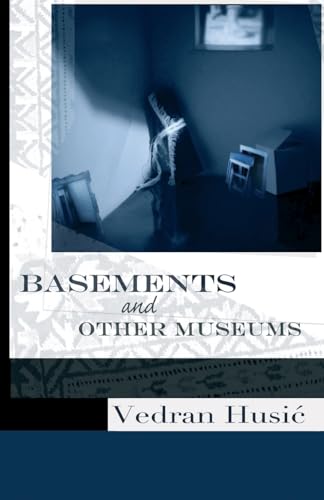

Every once in a while, a short story collection comes around that requires slow sipping—stories that silence you in the lamplight or make you pause, watch the outside daylife without really seeing it because you are still immersed in the world of the book. Such is the spell that Basements and Other Museums by Vedran Husić weaves.

Winner of the St. Lawrence Book Award from Black Lawrence Press, Basements cycles in and out of the tumultuous history of the Balkans—more specifically, Husić’s Bosnia and Herzegovina, where he was born. But the writer doesn’t overwhelm the reader with complicated backstory of the region’s past. Instead, we are often tossed into the middle of the anxieties of war or the unsettling peace that follows.

These are stories rooted in place and the loss of that place, stories anchored in the wars of the 1990s as much as in the Bosnian diaspora, where characters live in the present day in places like suburban Phoenix, Arizona, and wrestle with their inherited histories of violence. These stories interrogate borders and ethnicities, how a person who lives on the other side of town could be an enemy just as soon as they could be a friend, whether Serb or Croat, Christian or Muslim, Jew or atheist.

From the very first page, Husić’s stories come at you with the rushing velocity of the bullets that fill his collection. The opening “A Brief History of the Southern Slavs,” a micro-story, does excellent work to shape the rest of the collection not just by introducing the writer’s skillful lyricism but also by framing the overarching narrative. These are stories driven by characters who become “prisoners of ideas, then arrogant like all nonbelievers, then violent like all who regain their faith.” Ultimately, each story is a test tube in which the characters wrestle with ideology—whether religious attachment, nostalgia, romantic longing, or some other powerful force—and the stories end with a full embrace or rejection of what was first felt at the outset.

The characters we meet, such as Ivan Boric, a fictional Serbo-Croatian writer, are often consumed by an idea that morphs into something else entirely, characters who come face to face with profound loss. Boric, for instance, in “Witness to a Prayer,” is described as a writer who seeks to “[i]mprison beauty in a padded sentence,” to illustrate the “overlooked miracles of life.” Yet Boric, according to a narrator telling the tale in the style of a biography, is “embarrassed” by the sentimentality of his writing vocation, as if it is incomplete. The story shifts—surprisingly, as Husić often does—into a second section that reads more like lyrical fiction and less like biography. Here we see the character Boric from another side, a man who has fallen in love with the quiet of the world, who is consumed by the small beauties of life with his wife Vesna and daughter Mila. But as a Boric’s mind cascades through memories—glimpses in which he watches “Mila sleep in the candlelight”—the dark violence of trauma inserts itself until he must confront the truth that Mila has been killed by a “fragment of a mortar shell.” The miracles of life that he had tried to capture have evaporated, memory only dancing in the shadows of war. The narrator speculates at the story’s end that instead of sentimentalism perhaps Boric has been “trying to capture beauty and raise the dead.”

In this story and in others, Vedran Husić uses form to constantly destabilize the reader, to recreate the effect not just of war but also of exile, of longing. The story “Translated from the Bosnian” is written in the form of letters exchanged between a deceased father and his living wife and son. In the silence and white space between each exchanged letter, the longing and disconnect between characters is amplified. Another story, “Documentary,” cycles through linked first person monologues, as if each character was being interviewed as they try to describe Dario, the central figure in the story who is unable to be content in a changing world, to move on from love, to truly value the lives around him.

Time also is a character in these stories. Husić uses the slippages of memory combined with the complexity of point of view shifts as each character quests for truth. Central to these narratives, however, is a city that seems strangely unaltered by time and war, despite the many violences that happen in and around it. The city of Mostar acts as a constant place of physical as well as psychological return, bordering on the spiritual. Take this beautiful passage from “Deathwinked” when the narrator elegizes the city of his past:

Mostar, my city, you are far from me now, but I peek through the spyglass and you appear so near. In my third-floor apartment, in the neverdesperate America of my childhood dreams, at my desk, armed with pencil and paper, sensitive as a landmine, fumbling similes like live grenades, I, the young, triple-tongued poet, write down the name of my birthcity like the name of a former lover. Mostar. Mostar, my city, stunned quiet.

Husić invokes writers that similarly channel form for cerebral effect—from the poet Paul Celan to novelists Fyodor Dostoevsky, Leo Tolstoy, and the philosopher Søren Kierkegaard—and any reader who might be a fan of these heavy lifters would certainly do well to pick up Basements and Other Museums. Among contemporary writers, Husić reminds me of Orhan Pamuk, who in books like Snow similarly questions how a fractured present can somehow be traced back to a more intact past.

Husić invokes writers that similarly channel form for cerebral effect—from the poet Paul Celan to novelists Fyodor Dostoevsky, Leo Tolstoy, and the philosopher Søren Kierkegaard—and any reader who might be a fan of these heavy lifters would certainly do well to pick up Basements and Other Museums. Among contemporary writers, Husić reminds me of Orhan Pamuk, who in books like Snow similarly questions how a fractured present can somehow be traced back to a more intact past.

Vedran Husić’s Basements and Other Museums is a collection where absence is felt acutely, where characters become strangers to themselves. A monk at a Greek monastery in the book’s final story vocalizes what is perhaps the book’s central idea: “A man in doubt is therefore a man in perpetual exile.” This is a collection, after all, where belief is lost and found and lost again.