“I have this feeling, that all it will take will be one moment, even a tiny moment.”

When Kazuo Ishiguro won the Nobel Prize in Literature I was slightly disappointed. I was a “Harukist”—over the preceding eight months, I had been religiously reading the novels and short stories of Haruki Murakami. As a series they are recognizable as a related body of work with the same ideas, motifs, often a central piece of music and a certain brand of whiskey appearing with regularity. But with each new book, Murakami follows the growing roots of his literary tree to a new colony. To me, he seemed to have done just as much, if not more than Ishiguro and in a similar vein.

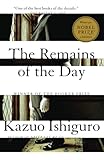

As with a lot of things in life though, I was uninformed. A conversation with a friend led us both to the conclusion that, despite our surprise, neither of us had read one of Ishiguro’s novels, nor did we know a lot about him. A quick Google search led me past The Booker Prize winning Remains of the Day, after reading a quote in which Ishiguro almost admitted he was bored writing it. In an interview with The Times Literary Supplement, he stated that writing Remains of the Day was almost too easy—“a bit like pushing a button all the time.”

As with a lot of things in life though, I was uninformed. A conversation with a friend led us both to the conclusion that, despite our surprise, neither of us had read one of Ishiguro’s novels, nor did we know a lot about him. A quick Google search led me past The Booker Prize winning Remains of the Day, after reading a quote in which Ishiguro almost admitted he was bored writing it. In an interview with The Times Literary Supplement, he stated that writing Remains of the Day was almost too easy—“a bit like pushing a button all the time.”

Eventually, I arrived at The Unconsoled—conversely, James Wood‘s comments that the novel had “invented its own category of badness” piqued my interest. While the conflicting conclusions of John Carey, describing it as a “masterpiece” led me to decide the novel would be my entry point into Ishiguro, albeit with the expectation of not finishing a book that has infuriated many. Instead, I found a book that struck me on a deeply personal level, through a story that paints a startlingly clear picture of the current trajectory of bewildering modern life.

The Unconsoled follows Mr. Ryder, an internationally renowned pianist, over the course of three days, as he arrives for a performance in a city in central Europe. Ryder’s three days are a cacophony of engagements most of which he cannot recall ever having agreed to. Indeed, as the people of the city begin to look to Ryder as the solution to all of their problems, the narrative becomes more and more baffling. Ideologically and physically labyrinthine, Ishiguro projects Ryder through a series of ever expanding, constantly changing events.

A series of encounters extensively developed but never fully resolved—this city in central Europe is malleable and ouroboric. For example, Ryder’s son Boris seems to function as a kind of a narratorial lighthouse, a source of happiness, relief, anger, and guilt, who he is constantly dragged away from by the people of the city and their needs. Regardless of how he makes Ryder feel, Boris is a reminder of Ryder’s role as a father—a redundant aspect of his character for the city, but a crucial part of his humanity.

In one instance, Boris is left in a cafe as Ryder is whisked away to the Sattler Monument for a press opportunity, after this his return to his son is further interrupted by musician Christoff’s insistence he attend a lunch. Ryder’s growing anxiety about having left his son melts away only as the lunch finishes, with the realization that he has been having lunch at the cafe he started in. In this novel, crescendoing bewilderment is often met with the briefest moments of relief (often via discovered geographical convenience), before Ryder is rapidly propelled into yet another tangled social web.

As a protagonist, Ryder is stripped of his control over himself—he becomes the focal point for a city of individuals wrapped up in their own concerns. With this in mind, it is perhaps unsurprising that Ishiguro began writing this novel after an 18-month press tour for Remains of the Day—a connection that allows the tentative planting of one foot in the real world, with regards to this surreal novel. Ishiguro has spoken of his writing a mixture of the unreal and familiar, which has made me think that Ryder’s experience of this central European city, published 23 years ago, is a useful analogy for the direction in which modern life is heading.

As a result, literary critic John Carey’s assessment of the novel being about stress is a useful starting point. In an interview with Charlie Rose, Ishiguro described the novel as being about the idea that we expectantly live our lives leading up to one big performance. A performance he simply defines as the one great event of our life we hope for and look forward to. An event that is surrounded by anxiety and demands our attention, but one that life does not stop for. We see this in Ryder, as he navigates the days preceding the concert, his thoughts are sidelined by the people of the city. Characters lost in their own concern look to Ryder as a tool to solve problems. He is foiled by his renown and the fact that he is in the city to perform amidst an artistic crisis, which makes him recognizable and accessible. There is an unwilling messianic quality to Ryder who is abused as a kind of whiteboard for the problems of the people.

It is this idea of accessibility relieving Ryder of his free will that is crucial. In the world of the book everyone knows one another intimately, all aware of the machinations of the city. Indeed, in some passages, Ishiguro even goes so far as to transplant his protagonist into the minds of others. Everything becomes public, an idea accentuated by the claustrophobically shifting geography of the novel—deployed by Ishiguro as a kind of temperature control for Ryder’s fluctuating levels of frustration, stress, and anxiety. One episode sees Ryder awoken and driven to an evening party in only his dressing gown. After dinner, as he is about to return to bed, he discovers he is already and always has been at his hotel. Often when Ryder appears to have left a place, he will go through a door after an event and find himself back where he left from.

Ryder’s experience of this intimate, gossip-ridden, self-obsessed city is accentuated because of his celebrity. A celebrity comfortably replicated by the way we use technology. Indeed, this technology thrusts us into the center of our own small community and makes us accessible regardless of where we are. We represent ourselves with a variety of online profiles that serve different functions and are interacted with in different ways. Similar to the way Ryder serves a variety of both perceived and pre-empted functions for the people of the city.

The fact that these profiles are never “turned off” means you lose the element of control over how and when people contact you. It conjures the same access-all-hours situation that assaults and irritates Ishiguro’s protagonist. Often multiple events appear without warning, detracting from the importance of Ryder’s performance and contributing to his lack of agency and rising anxiety. We are presented with a character who is overwhelmed and unable to locate his sense of priority—an experience replicated by opening and unlocking your phone to a mountain of notifications from a variety of communicative platforms—a situation presented through the interiority of the narrative. The protagonist’s actions are often introduced with lines like, “Suppressing a sense of panic, I set about formulating something to say that would sound at once dignified and convincing.” Ishiguro gives us a character who feels harassed and, despite his acclaim, rendered inadequate by the demands of those around him—reflective of the kind of stress that can accompany the unnatural levels of interaction technology and social media bring.

Despite his renown, Ryder is rarely assured as he stumbles through social encounters, which in turn, elicit the kind of strong reactions that are emblematic of the sensitivity of the Internet. So Ryder’s predicament seems to be similar to ours: he is the centre of a small, inescapable community to which he feels obligated and is open all hours. Of course, the novel is an accentuation of real life. Our interactions with this “community” can be beneficial and are often treasured, yet, they have the ability to cause bewilderment, anxiety, and stress, while also being a distracting from the important things in life. This is best exemplified by Ryder constantly being pulled away from Boris, his son—a representation of truly important duty, and whose company the protagonist is his most emotional and human in.

Thankfully, the novel represents a world more accentuated than our own. In the book, Christoff, a mechanical cellist, is the musical predecessor socially dismantled by the new artistic beginning Ryder symbolizes to the city. His social destruction is based on the precedential hope of Ryder calling out the error in his musical philosophy. Ishiguro usefully convolutes Ryder’s motivation for contradicting Christoff: “I could feel, almost physically, the tide of respect sweeping towards me.” The protagonist is encouraged by the mob and crucially by what they expect of him. Ironically, a rare scene in which Ryder is finally assured represents one of the fullest realizations of his lack of agency—even in his area of expertise he still succumbs to the demands on the city.

So the idea is formed of two aspects. The first is accessibility and knowledge, seen in the way we are always available online to our small community and the manner in which Ryder is viewed as a tool, to be utilized, for a town in crisis. The result of this is pressure, to constantly respond and engage with what is going on around us, made immediate by the Internet, however distracting it may be. At the moment, we are privileged enough not to be in Ryder’s situation stagnantly spinning like a hamster on a wheel.

The novel also goes beyond this: with the idea of expectation and precedent. The public nature of our lives means there is recorded history to our actions. Ryder is expected to be the advent of something new and better for the art world in the city. Even before his arrival, they have created a character for him, a mold to fill. In the same way that social media encourages experience rating and expected precedents. Indeed, the precedent set by three, four, or five stars alters experience in the same way Ryder is seen to be pushed and pulled even in the subject in which he is an expert. There is a dangerous circularity to living up to expectations, especially when this behavior is well received.

Currently, technology and social media are similar to the most basic definition of Ryder’s distractions. Put simply, the fact that he has to go to a lunch, or take a photo for the press. Upon his arrival in the hotel lobby, in the opening pages, he no longer decides where he goes or what he does, which contributes to a rising distraction from his performance and an anxiety presented in bewilderment and lack of action. And it’s the same for us: problems and engagements via technology can distract from being human by creating an overbearing sense of duty on a social and working level.

The Unconsoled, however, is more complex than this—it is wonderfully and terrifyingly forward looking. Ryder is often the center of events because of who he is and throughout the novel he is prodded and poked, cajoled and encouraged into behaving a certain way. He becomes a symbol of how the people of the city expect him to be. Any forays he makes into being himself are often met with strong negative reactions. When Mr. Hoffman, the hotel manager, questions Ryder’s reluctance to change rooms, he puts the pressure on the protagonist. Indeed, he accuses Ryder of being oddly attached to the room when in reality, it is he who is strangely insistent on the room change. Ryder is consistently forced into a behavioral corner, an easily comparable situation to a life increasingly dominated by the way we are being presented and recorded via the Internet.

The Unconsoled explores the slippery slope of anxiety caused by accessibility and perceived responsibility. In this sense, it can work as an analogy for the direction in which we are heading—as we make ourselves more available and knowable via technology and the Internet, we become subject to the same kind of pressures Ryder experiences due to his fame. And resultantly, subject to unending levels of additional social pressure. Ultimately, at the heart of this inescapable, complex maze of a novel is a character who is constantly losing control of himself because of his inability to disengage.