For years I have been unsuccessfully recommending true crime books to friends. The second you tell someone you’ve just read a mind-blowing book about Jeffrey Dahmer that they simply must read, they start to back away from you. The first rule of reading true crime, evidently, is that you don’t talk about reading true crime.

And yet I’m clearly not the only one reading (or watching) it. Books by Ann Rule and Harold Schechter are perennial bestsellers; the podcast Serial and the Netflix series Making a Murderer have led to a resurgence in true crime popularity, with more people reading it than ever before.

The question is, why?

Does true crime permit people to “ventilate their sadistic impulses…in a socially acceptable way”? Or does it serve as a “kind of guidebook for women, offering useful tips for staying safe”? Or do these stories prompt us to “take a long, hard look at the contexts in which such atrocities arise” and “how we as a society deal with them”?

None of those reasons resonate with me, although that last one comes closer than many. So why do I read (and in some cases, re-read) these narratives that describe such horrifying things, things that scare me and break my heart? Why can’t I look away?

Some of the first true crime books I read were the ones everyone reads: Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood, the narrative of the 1959 murders of a Kansas farm family, is respectable enough to be on many high school reading lists. Likewise, Vincent Bugliosi’s Helter Skelter, about the murder of pregnant actress Sharon Tate and several others, perpetrated by Charles Manson and members of his “family,” has sold many millions of copies. More recent classics like David Simon’s Homicide: A Year on the Killing Streets and Robert Kolker’s Lost Girls: An Unsolved American Mystery, also don’t require digging to find. Simon’s journalistic account of a Baltimore homicide department and the cases they worked became the basis for the TV show Homicide: Life on the Street (and arguably paved the way for The Wire); Kolker’s investigation into the lives of the women killed by the (as yet uncaught) Long Island Serial Killer was named on many “best of” book lists of 2013.

Some of the first true crime books I read were the ones everyone reads: Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood, the narrative of the 1959 murders of a Kansas farm family, is respectable enough to be on many high school reading lists. Likewise, Vincent Bugliosi’s Helter Skelter, about the murder of pregnant actress Sharon Tate and several others, perpetrated by Charles Manson and members of his “family,” has sold many millions of copies. More recent classics like David Simon’s Homicide: A Year on the Killing Streets and Robert Kolker’s Lost Girls: An Unsolved American Mystery, also don’t require digging to find. Simon’s journalistic account of a Baltimore homicide department and the cases they worked became the basis for the TV show Homicide: Life on the Street (and arguably paved the way for The Wire); Kolker’s investigation into the lives of the women killed by the (as yet uncaught) Long Island Serial Killer was named on many “best of” book lists of 2013.

But I have also read a lot of true crime that doesn’t make the bestseller lists. There was Stacy Horn’s surprisingly gentle The Restless Sleep: Inside New York City’s Cold Case Squad, about murder cases solved (or not) years after they were given up as unsolvable. Although largely a police procedural, Horn’s book is also notable for the details given about the victims: teen Christine Diefenbach was on her way to buy milk and a magazine; drug dealers Linda Leon and Esteban Martinez were killed while their three young children listened in the next room. There was also Jeanine Cummins’s A Rip in Heaven: A Memoir of Murder and Its Aftermath, an excruciating blend of family memoir and crime. When Cummins’s two cousins and her brother went to see an abandoned area bridge that doubled as a teen hangout spot, they were assaulted by a group of men who raped the women and finished by pushing all three of their victims into the Mississippi River to drown. Surviving and crawling to safety, Tom Cummins then underwent a second ordeal when the local police targeted him as the killer of his cousins. Although I don’t really read true crime to learn how to protect myself, I did take away at least one lesson from that book: Lawyer up.

But I have also read a lot of true crime that doesn’t make the bestseller lists. There was Stacy Horn’s surprisingly gentle The Restless Sleep: Inside New York City’s Cold Case Squad, about murder cases solved (or not) years after they were given up as unsolvable. Although largely a police procedural, Horn’s book is also notable for the details given about the victims: teen Christine Diefenbach was on her way to buy milk and a magazine; drug dealers Linda Leon and Esteban Martinez were killed while their three young children listened in the next room. There was also Jeanine Cummins’s A Rip in Heaven: A Memoir of Murder and Its Aftermath, an excruciating blend of family memoir and crime. When Cummins’s two cousins and her brother went to see an abandoned area bridge that doubled as a teen hangout spot, they were assaulted by a group of men who raped the women and finished by pushing all three of their victims into the Mississippi River to drown. Surviving and crawling to safety, Tom Cummins then underwent a second ordeal when the local police targeted him as the killer of his cousins. Although I don’t really read true crime to learn how to protect myself, I did take away at least one lesson from that book: Lawyer up.

A Rip in Heaven was the first true crime book that I tried to recommend to friends. I’m sure no one took me up on it, and I can’t blame them; re-reading the book now, my stomach is in knots for the victims because I know what’s coming. But I didn’t learn my lesson: when I read John Backderf’s graphic memoir My Friend Dahmer, about his high school acquaintanceship with future serial killer Jeffrey Dahmer, I wanted everyone to read it. In that book I learned that Jeffrey Dahmer, on a high school field trip to Washington D.C., got himself and a couple of friends invited into vice-president Walter Mondale’s office. All of a sudden it was clearer how Dahmer, in subsequent years, proved to be adept at talking himself out of sticky situations with police officers. How do you not recommend the book from which you learn that? Overall Backderf painted a picture of such a struggling and disturbed young man that, in his preface, he had to tell his readers to “pity him [Dahmer], but don’t empathize with him.”

A Rip in Heaven was the first true crime book that I tried to recommend to friends. I’m sure no one took me up on it, and I can’t blame them; re-reading the book now, my stomach is in knots for the victims because I know what’s coming. But I didn’t learn my lesson: when I read John Backderf’s graphic memoir My Friend Dahmer, about his high school acquaintanceship with future serial killer Jeffrey Dahmer, I wanted everyone to read it. In that book I learned that Jeffrey Dahmer, on a high school field trip to Washington D.C., got himself and a couple of friends invited into vice-president Walter Mondale’s office. All of a sudden it was clearer how Dahmer, in subsequent years, proved to be adept at talking himself out of sticky situations with police officers. How do you not recommend the book from which you learn that? Overall Backderf painted a picture of such a struggling and disturbed young man that, in his preface, he had to tell his readers to “pity him [Dahmer], but don’t empathize with him.”

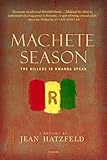

Empathizing with anyone in true crime narratives is tricky business. Of course you empathize with the victims, although you hope you are never among their ranks. What is even more horrifying is when you recognize something in the experiences of the killers. It has been years since I read Jean Hatzfeld’s oral history of the Rwandan genocide, Machete Season, in which he interviewed Hutus who had been charged with multiple murders of their Tutsi neighbors, and yet I will never forget the chill I got when I read this line: “Killing was less wearisome than farming.” I grew up on a farm, where we worked all the time, and then bad weather would come along and ruin all your work anyway. God help me…just a little bit…I got what the murderer was saying.

Empathizing with anyone in true crime narratives is tricky business. Of course you empathize with the victims, although you hope you are never among their ranks. What is even more horrifying is when you recognize something in the experiences of the killers. It has been years since I read Jean Hatzfeld’s oral history of the Rwandan genocide, Machete Season, in which he interviewed Hutus who had been charged with multiple murders of their Tutsi neighbors, and yet I will never forget the chill I got when I read this line: “Killing was less wearisome than farming.” I grew up on a farm, where we worked all the time, and then bad weather would come along and ruin all your work anyway. God help me…just a little bit…I got what the murderer was saying.

This autumn, for the first time, I read Dave Cullen’s multiple-award-winning narrative Columbine, about the 1999 school shootings in Littleton, Colo.. At the time I hadn’t paid much attention to the shootings—you live in a culture that loves guns, you’re going to have school shootings, I figured—but it gives me pause now to read about the events and the psyches of Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold, the shooters, and to read about how involved both their sets of parents were in their lives. I say “involved,” although it is impossible to know, really, how close either boy was to his parents. If you read enough true crime you start to question even basic vocabulary. What does it mean to be involved? Or close? Or a psychopath?

This autumn, for the first time, I read Dave Cullen’s multiple-award-winning narrative Columbine, about the 1999 school shootings in Littleton, Colo.. At the time I hadn’t paid much attention to the shootings—you live in a culture that loves guns, you’re going to have school shootings, I figured—but it gives me pause now to read about the events and the psyches of Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold, the shooters, and to read about how involved both their sets of parents were in their lives. I say “involved,” although it is impossible to know, really, how close either boy was to his parents. If you read enough true crime you start to question even basic vocabulary. What does it mean to be involved? Or close? Or a psychopath?

Because I have little boys, the subjects of boys and depression and anger are now all subjects that are on my radar. As such, I followed up Columbine with Sue Klebold’s (mother of Dylan) memoir A Mother’s Reckoning. The day I picked it up from the library I had both my boys with me, and we headed back to the kids’ nonfiction section so they could browse, and I could stand nearby looking over books for myself. As I paged through the Klebold memoir, my concentration was interrupted by half-shouts from the kids’ computer area: “Shoot them!! Come on, kill ‘em kill ‘em kill ‘em, God, you’re a terrible shot, move over and let me do it.” About four tweeny little boys were playing what must have been some multi-player shoot-‘em-up game. What were the odds, I wondered, that I would be listening to these nice little suburban boys chant variations of the words “shoot” and “kill,” while I paged through a book written by the heartbroken mother of a murderer?

Because I have little boys, the subjects of boys and depression and anger are now all subjects that are on my radar. As such, I followed up Columbine with Sue Klebold’s (mother of Dylan) memoir A Mother’s Reckoning. The day I picked it up from the library I had both my boys with me, and we headed back to the kids’ nonfiction section so they could browse, and I could stand nearby looking over books for myself. As I paged through the Klebold memoir, my concentration was interrupted by half-shouts from the kids’ computer area: “Shoot them!! Come on, kill ‘em kill ‘em kill ‘em, God, you’re a terrible shot, move over and let me do it.” About four tweeny little boys were playing what must have been some multi-player shoot-‘em-up game. What were the odds, I wondered, that I would be listening to these nice little suburban boys chant variations of the words “shoot” and “kill,” while I paged through a book written by the heartbroken mother of a murderer?

It struck me that day that there is no use pretending that violence is something that only happens to the Other, perpetrated by the Other. We are surrounded by it on all sides, even when we try to construct our safe enclaves. Violence is a great exploiter. All it requires is bad luck, a foolish miscalculation, human weakness, or some combination of those factors to make its presence felt. Although monstrous deeds are front and center in these true crime narratives, they are not really about monsters. These are stories about humans: we are messy, we are imperfect; sometimes it is easy to succumb to anger and hatred; sometimes we are the victims, at other times, the perpetrators.

But if there is no use hiding from violence, equally there is no denying the presence of its flip side: compassion. And there is also compassion in true crime narratives: in the doggedness of the cops and investigators who are employed by society to try and solve cases; in the dedication of the legal system workers who prepare for trials for weeks, months, years; not least in the fortitude of authors who research and write these stories to bring them out into the open. All of those people work to restore dignity to those whose dignity, along with their safety or their mental equilibrium or their lives, was taken away from them.

True crime is not easy to read. It is even harder to talk about, and it’s almost impossible to recommend to other readers (without sounding a bit like a prurient psychopath yourself). But if 2017 taught us only one thing, I would hope it is that before you can start to try and solve problems, you have to admit problems exist. We have to tell the stories, and we also have to listen.

That is why I read true crime.

Image Credit: Flickr/Ash Photoholic.