I was pregnant with my second child for most of the year and I was also working from home, which meant I was very sedentary and slothful, and able to spend a lot of time reading articles that made me miserable. And since I was working on a book, and the pace and nature of that work were utterly different from any other kind of work I’ve done, I was grumpy and anxious a lot of the time even without reading anything at all. And I worried about being miserable and anxious and grumpy, and sedentary and slothful, wondering what it would do to the fetus, and whether the fetus would want to be around someone like me.

The reading I did while gestating the baby and my book was catch-as-catch-can and felt mostly like a reprieve and a cheat when I should have been working or doing something civic-minded. Books and the time they went with are blurring together for some reason. I think I read and was ruined by Housekeeping last year, but I can’t be certain it wasn’t this year. I think I read Private Citizens this year and found it spiky and perfect, but I’m not actually sure I didn’t read it in 2016. I do know this year I read The Idiot, which is among other things a delightful evocation of ostensibly fruitless but formative romantic pining, and Sport of Kings, which is absurdly ambitious and devastating. I read The Regional Office Is Under Attack, which is weird and transporting. I gratefully blew off my work for New People, The Windfall, Marlena, The Reef, Hunger, and Conversations with Friends. I read White Tears and The Changeling and Frankenstein in Baghdad on the bus to the OBGYN and marveled at the ways great writers are documenting the effects of the unholy past on the unholy present. I read 10:04 in a lovingly serene and receptive state after spending $60 to float in a very salty pool in the dark (I was trying to make the fetus turn head-down). When I was freaked out about everything the only book that sort of soothed me was the phenomenal new translation of The Odyssey, which is modern but not jarringly so, and highlights the sense of human continuity we apprehend from an ancient text. I re-read Off Course, a wonderful California novel that has become one of my favorite books in the last few years. I re-read A Suitable Boy to get ready for A Suitable Girl, which is allegedly arriving in 2018 and which I’ve been waiting for my entire adult life. I read The Golden Road, Caille Millner’s gemlike memoir about growing up. I read a Word document containing the first half of Michelle Dean’s excellent forthcoming literary history Sharp, and I’m clamoring for the rest of it. I read a Word document containing the entirety of Meaghan O’Connell’s forthcoming essay collection, And Now We Have Everything, and it is a stunningly insightful book that I’m hesitant to say is about motherhood because it might turn away people who might otherwise profit from it. I loved my colleagues Edan and Claire and Sonya’s novels Woman No. 17 and The Last Neanderthal and The Loved Ones, which are about motherhood (and fatherhood, and daughterhood, and a lot of other things too). More mothers: I cried over Mr. Splitfoot in an airplane after reading Samantha Hunt’s “A Love Story” in The New Yorker. The book I thought about most during my gestational period was Mathias Énard’s Compass, which is a love story of a different kind. I don’t think I’ve read another book so deft in transmitting both the desire and the violence that are bound up in the production of knowledge, another complicated act of creation.

The reading I did while gestating the baby and my book was catch-as-catch-can and felt mostly like a reprieve and a cheat when I should have been working or doing something civic-minded. Books and the time they went with are blurring together for some reason. I think I read and was ruined by Housekeeping last year, but I can’t be certain it wasn’t this year. I think I read Private Citizens this year and found it spiky and perfect, but I’m not actually sure I didn’t read it in 2016. I do know this year I read The Idiot, which is among other things a delightful evocation of ostensibly fruitless but formative romantic pining, and Sport of Kings, which is absurdly ambitious and devastating. I read The Regional Office Is Under Attack, which is weird and transporting. I gratefully blew off my work for New People, The Windfall, Marlena, The Reef, Hunger, and Conversations with Friends. I read White Tears and The Changeling and Frankenstein in Baghdad on the bus to the OBGYN and marveled at the ways great writers are documenting the effects of the unholy past on the unholy present. I read 10:04 in a lovingly serene and receptive state after spending $60 to float in a very salty pool in the dark (I was trying to make the fetus turn head-down). When I was freaked out about everything the only book that sort of soothed me was the phenomenal new translation of The Odyssey, which is modern but not jarringly so, and highlights the sense of human continuity we apprehend from an ancient text. I re-read Off Course, a wonderful California novel that has become one of my favorite books in the last few years. I re-read A Suitable Boy to get ready for A Suitable Girl, which is allegedly arriving in 2018 and which I’ve been waiting for my entire adult life. I read The Golden Road, Caille Millner’s gemlike memoir about growing up. I read a Word document containing the first half of Michelle Dean’s excellent forthcoming literary history Sharp, and I’m clamoring for the rest of it. I read a Word document containing the entirety of Meaghan O’Connell’s forthcoming essay collection, And Now We Have Everything, and it is a stunningly insightful book that I’m hesitant to say is about motherhood because it might turn away people who might otherwise profit from it. I loved my colleagues Edan and Claire and Sonya’s novels Woman No. 17 and The Last Neanderthal and The Loved Ones, which are about motherhood (and fatherhood, and daughterhood, and a lot of other things too). More mothers: I cried over Mr. Splitfoot in an airplane after reading Samantha Hunt’s “A Love Story” in The New Yorker. The book I thought about most during my gestational period was Mathias Énard’s Compass, which is a love story of a different kind. I don’t think I’ve read another book so deft in transmitting both the desire and the violence that are bound up in the production of knowledge, another complicated act of creation.

In October I had the baby. I wouldn’t suggest that anyone have a baby just to shake things up, but babies have a way of returning you to your body and adjusting your relationship to time that I’d hazard is difficult to find elsewhere in the arena of positive experiences. First you have the singular experience of giving birth; then you have the physical reminders of that experience, and a baby. If you are lucky you get good hormones (if you are spectacularly lucky you get paid leave, or have a spouse who does). The morning she was born I looked at the baby lying in her bassinet and felt like the cat who swallowed the canary, or a very satisfied hen. Animal similes suggest themselves because it is an animal time: you smell blood and leave trails of it on the hospital floor; milk oozes. You feel waves of such elemental fatigue that rational thought and speech seem like fripperies for a younger species. Even now, nine weeks later, sneezing reminds me viscerally of what the flesh endured.

This is what I mean when I say the experience returns you to your body. If it’s your second child, it also makes you a time traveler. I spent my first child’s infancy desperate to slow down time, to fully inhabit this utterly strange nesting season of my life and hers before we were both launched into the future. When the second baby was born I got the unhoped-for chance to live in that season again. I had forgotten so much: the comically furtive and then plucky look a newborn gets when she is near the breast, and the bizarre thing her eyes do when she’s eating—zipping back and forth like a barcode scanner apprehending some ancient sequence. The sound she makes after sneezing, like a little wheeze from an oboe.

Since, during this period, I felt I had a legitimate excuse to not read every dire news item for at least a couple of weeks, and since I experienced a wonderful if brief disinclination to open Twitter, and since sometimes I got to sit in clean linen sheets that are my prized possession and nurse a tiny brown-furred baby, I fell in love both with the baby and with every book I touched. I started re-reading Mating when I was waiting to give birth and finished it the week after. I read it for the first time three years ago when my older daughter was born and felt so incredibly altered by it then, and I slipped back into that state immediately. Right after Mating I read Mortals, and after Mortals, I read Chemistry, and forthcoming novels The Parking Lot Attendant and That Kind of Mother, and I loved them all too.

Since, during this period, I felt I had a legitimate excuse to not read every dire news item for at least a couple of weeks, and since I experienced a wonderful if brief disinclination to open Twitter, and since sometimes I got to sit in clean linen sheets that are my prized possession and nurse a tiny brown-furred baby, I fell in love both with the baby and with every book I touched. I started re-reading Mating when I was waiting to give birth and finished it the week after. I read it for the first time three years ago when my older daughter was born and felt so incredibly altered by it then, and I slipped back into that state immediately. Right after Mating I read Mortals, and after Mortals, I read Chemistry, and forthcoming novels The Parking Lot Attendant and That Kind of Mother, and I loved them all too.

Being with the baby and reading deeply and more or less avoiding the things that make me miserable was such an unanticipated return to Eden that even the bad things I now remembered about having a baby were good: the strange combination of agitation and dullness that enswaddled me when the sun went down and made me weep; the sudden urge to throw beloved visitors out of the house; visions of stumbling, of soft skulls crushed against sharp corners; fear of contagion; agonizing knowledge of other babies crying and drowning and suffering while your own baby snuffles contentedly in a fleece bag.

But even when the blues fluoresced what registered was not the badness of the thoughts, but their intensity. The shitty hospital food you eat after expelling a baby is the best food you’ve ever had because you had a baby and you didn’t die. And like a person on drugs who knows a cigarette is going to taste amazing or a song will sound so good, an exhausted, oozing postpartum woman can do her own kind of thrill-seeking. I re-read Under the Volcano, which really popped in my altered state. It’s a hard book to follow but I found to my delight that I’ve now read it enough I’m no longer spending a lot of time trying to understand what is going on. Its insane, calamitous beauty was perfect for my technicolor emotional state; rather than despairing over my inability to form a sentence I put myself in the hands of a pro, shaking though Malcolm Lowry’s were as he wrote.

But even when the blues fluoresced what registered was not the badness of the thoughts, but their intensity. The shitty hospital food you eat after expelling a baby is the best food you’ve ever had because you had a baby and you didn’t die. And like a person on drugs who knows a cigarette is going to taste amazing or a song will sound so good, an exhausted, oozing postpartum woman can do her own kind of thrill-seeking. I re-read Under the Volcano, which really popped in my altered state. It’s a hard book to follow but I found to my delight that I’ve now read it enough I’m no longer spending a lot of time trying to understand what is going on. Its insane, calamitous beauty was perfect for my technicolor emotional state; rather than despairing over my inability to form a sentence I put myself in the hands of a pro, shaking though Malcolm Lowry’s were as he wrote.

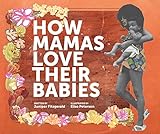

It hasn’t all been déjà vu. There have been new things, some of them bad: namely the feeling of being driven absolutely bananas by my poor sweet firstborn, who is no longer tiny and blameless and new, but a harum-scarum toddler who jumps on the bed and windmills her arms and kicks and screams WAKE UP MAMA and refuses to put on her jacket. On this front one of the random galleys that pile up in the vestibule was a surprise hit—a children’s book from the Feminist Press called How Mamas Love Their Babies. My daughter loves this book, which has beautiful photo collage illustrations. It is a progressive book that encourages workers’ solidarity in a way I was not necessarily prepared to address with a just-turned-three-year-old but am now trying to do in my poky fashion (“Some mamas dance all night long in special shoes. It’s hard work!” the book reads, and my child peers inquisitively at a photo of platform lucite heels). It also helps me: I look at myself in the mirror and note that some genetic vandal has lately streaked what looks like raspberry jam across the skin of my hips and one (!) breast (“Some mamas care for their babies inside their own bodies,” the book reminds me). When the baby was three weeks old I got pneumonia, and that was a bad new sensation too, although even that interlude had its attractions. I discovered coconut water, and read Swamplandia in a febrile, almost louche state of abandon in my increasingly musty sheets, a perfect complement to the novel’s climate—its rotting house and the visions and moods of its protagonists.

It hasn’t all been déjà vu. There have been new things, some of them bad: namely the feeling of being driven absolutely bananas by my poor sweet firstborn, who is no longer tiny and blameless and new, but a harum-scarum toddler who jumps on the bed and windmills her arms and kicks and screams WAKE UP MAMA and refuses to put on her jacket. On this front one of the random galleys that pile up in the vestibule was a surprise hit—a children’s book from the Feminist Press called How Mamas Love Their Babies. My daughter loves this book, which has beautiful photo collage illustrations. It is a progressive book that encourages workers’ solidarity in a way I was not necessarily prepared to address with a just-turned-three-year-old but am now trying to do in my poky fashion (“Some mamas dance all night long in special shoes. It’s hard work!” the book reads, and my child peers inquisitively at a photo of platform lucite heels). It also helps me: I look at myself in the mirror and note that some genetic vandal has lately streaked what looks like raspberry jam across the skin of my hips and one (!) breast (“Some mamas care for their babies inside their own bodies,” the book reminds me). When the baby was three weeks old I got pneumonia, and that was a bad new sensation too, although even that interlude had its attractions. I discovered coconut water, and read Swamplandia in a febrile, almost louche state of abandon in my increasingly musty sheets, a perfect complement to the novel’s climate—its rotting house and the visions and moods of its protagonists.

During early nights of nursing I read a galley of a memoir by a writer who also got good hormones and who became addicted to having babies, having five in fairly rapid succession. If nothing else, I understood the irrational drive to overabundance. In the first weeks of this new baby’s life I astonished myself by wanting more, more, more. Around week five I actually googled “is it morally wrong to have a third child,” and if you are a well-fed, utilities-using first-worlder like me, yes, not to mention yes, in philosophical terms (not to mention we can’t afford it, not to mention it would surely drive me batshit). Everything you read about life on this planet, including some of the novels I read this year, suggests you should not have children, and if you must, that you should have only as many as you have arms to carry them away from danger. Even that formulation is a consoling fallacy.

Things are less technicolor now, but the hormones are still there, propping me up. (I read over this and see they’ve even led me to write a somewhat revisionist history of what the past few weeks have been like.) Last week, week eight, I finally read Open City, which is a few years old but speaks to the state of the world today in a way that is depressing. I love how it is a novel of serious ideas and style, but is also approachable and pleasure-making for its reader. I love that it is a humane book even as it is gimlet-eyed. Now I’m reading Go, Went, Gone by Jenny Erpenbeck and finding it similarly humane and gimlet-eyed and serious and pleasure-making. It is about the state of the world at this moment. It also speaks to the double consciousness of people like its protagonist, who are living not necessarily with suffering but with a metastasizing awareness of suffering, and how it changes them, and this is on my mind. The novel also seems to be about time and space and how people are altered when their time and space are altered. It’s about the difference, not between “us” and “them,” but between “you” and “you.” I’m thinking about that too as I time travel this winter.

Things are less technicolor now, but the hormones are still there, propping me up. (I read over this and see they’ve even led me to write a somewhat revisionist history of what the past few weeks have been like.) Last week, week eight, I finally read Open City, which is a few years old but speaks to the state of the world today in a way that is depressing. I love how it is a novel of serious ideas and style, but is also approachable and pleasure-making for its reader. I love that it is a humane book even as it is gimlet-eyed. Now I’m reading Go, Went, Gone by Jenny Erpenbeck and finding it similarly humane and gimlet-eyed and serious and pleasure-making. It is about the state of the world at this moment. It also speaks to the double consciousness of people like its protagonist, who are living not necessarily with suffering but with a metastasizing awareness of suffering, and how it changes them, and this is on my mind. The novel also seems to be about time and space and how people are altered when their time and space are altered. It’s about the difference, not between “us” and “them,” but between “you” and “you.” I’m thinking about that too as I time travel this winter.

I know I need to prepare for the moment when all this gladness provided gratis by Mother Nature will deflate and disappear like a wet paper bag. And there will be a time—I feel it coming on as I type this and hope the baby stays asleep in her bouncer—when the deep satisfaction of one kind of generative act, this bodily one, will be supplanted with the need for other kinds of creation. I think Cole and Erpenbeck’s novels will help me with these eventualities. I’m counting on them, and on all the beautiful things I hope to read next year. You know what they say about books: they’re like babies; when you have one you’re never alone.

More from A Year in Reading 2017

Don’t miss: A Year in Reading 2016, 2015, 2014, 2013, 2012, 2011, 2010, 2009, 2008, 2007, 2006, 2005