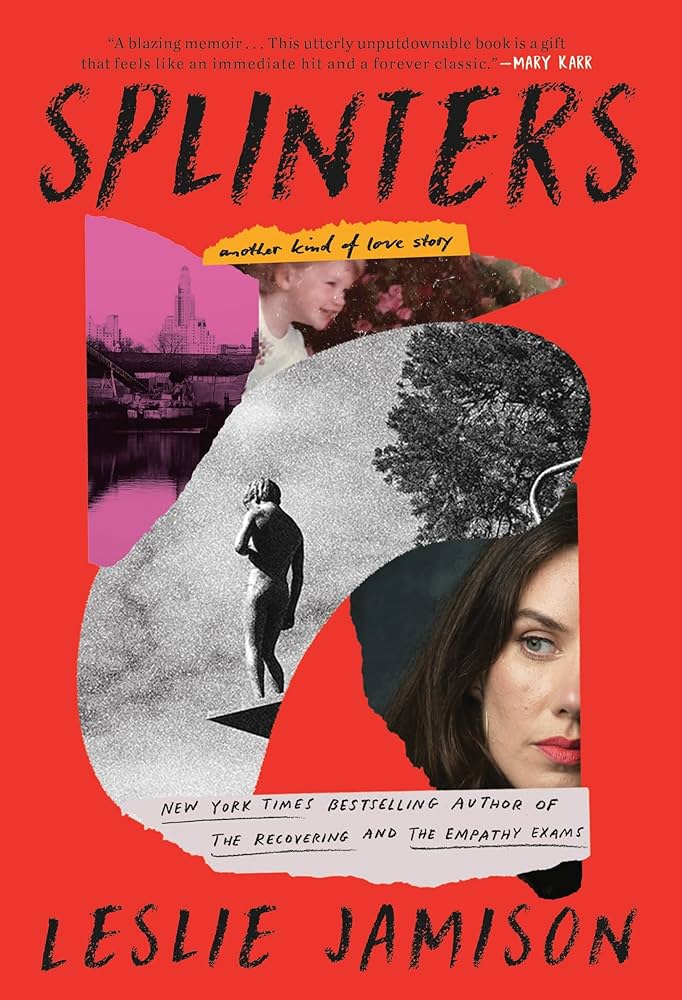

When I first heard that Leslie Jamison was writing a memoir about early motherhood and divorce, I was excited to read a book on these topics with Jamison’s now-trademark blend of memoir and cultural criticism, archival work, and reporting. She’s been working in, and honing, this mode since her breakout hit The Empathy Exams; through her follow-up, The Recovering, the addiction memoir to rule all addiction memoirs; and Make It Scream, Make It Burn, which bolsters reported essays with just enough memoir to make them feel intimate. But Splinters: Another Kind of Love Story is even better than the book I’d imagined. An unexpected pivot away from the hybrid mode, Splinters is pared down, spare—a deeply, entirely personal story of Jamison falling deeply in love with her daughter while her marriage crumbles around them. It’s a thrilling surprise to see an artist swerve away from the style they’ve been refining for a decade, and even more thrilling when the new mode feels somehow even truer to their voice and vision.

When I first heard that Leslie Jamison was writing a memoir about early motherhood and divorce, I was excited to read a book on these topics with Jamison’s now-trademark blend of memoir and cultural criticism, archival work, and reporting. She’s been working in, and honing, this mode since her breakout hit The Empathy Exams; through her follow-up, The Recovering, the addiction memoir to rule all addiction memoirs; and Make It Scream, Make It Burn, which bolsters reported essays with just enough memoir to make them feel intimate. But Splinters: Another Kind of Love Story is even better than the book I’d imagined. An unexpected pivot away from the hybrid mode, Splinters is pared down, spare—a deeply, entirely personal story of Jamison falling deeply in love with her daughter while her marriage crumbles around them. It’s a thrilling surprise to see an artist swerve away from the style they’ve been refining for a decade, and even more thrilling when the new mode feels somehow even truer to their voice and vision.

I had the immense pleasure of sitting down with the author over coffee and pastries to talk about the creative choices that went into her most intimate, glistening work yet.

Lilly Dancyger: You’re such a master of the hybrid form, weaving research and other people’s stories into your personal narrative. And this book really stands out for its different approach. I’d love to hear about the process of deciding that this story needed to be told in this more straightforward way—just personal narrative.

Leslie Jamison: One of the very first things I understood about this book was its unit size: These shards of experience—jagged, piercing pockets of prose that I began to think of as splinters—felt like the way that I wanted to write about motherhood, and the pain of my marriage breaking apart. Once this sense of form arrived, I started to like the idea of the whole book having this very whittled quality where it was just these searing moments that would feel close to my lived experience the whole time. Very sensory, very embodied, very immediate. That felt like right focal distance for this story.

I knew I wanted to engage with art—with various forms of beauty that had been some of the materials of my survival during this period—but I wanted those engagements to come from within the dramatic action of the story, rather than feeling like a distinct thread of criticism. So the text is full of these museum moments—where I’m engaging with art, or my daughter and I are in these spaces of art—and it’s a kind of critical engagement, but it’s almost like visceral criticism happening through the body—happening in scene, and through the senses.

LD: I’m curious about that fragmented or splintered form and the structure that you built with it. How did you think about where and when and how to bring in the little bits of flashbacks and other timelines?

LJ: I knew I wanted the book to begin in this particular moment of leaving my marriage—moving into a sublet beside a firehouse, in the bitter middle of winter—and feeling this wonder at my daughter, who was very young and just beginning to engage with the world, watching her consciousness take shape alongside a lot of ugliness and grief. That simultaneity was the beginning of the book for me: I wanted to find a way to represent these experiences of wonder and grief so tangled together. I knew I wanted to write that firehouse sublet as a place of beginning (a friend called it our birth canal). And then I wanted to tell you how we got there, which is the first section, and where it went from there, which second section. So that was how I understood the movements of the book. And then within those larger movements I wanted there to be these sharp, crystalline fragments.

LD: It’s really cool to hear that the little splinters were the origin point, because they do really define the feeling of the thing. They’re just so precise—whittled is a great word for it. I wondered also about the scene-building that went into each of these little moments. Do you start with the tiny, precise little details and build a scene around those? Or do you start with like, I need a scene where this happens, and then find the details to animate it?

LJ: I think it’s a combination. There’s always a reason I’m going into the scene, and also always a lot of things that emerge and surprise me once I’m in there. It’s like, you go into the bedroom looking for your keys, and maybe you find your keys in there, but there’s also a photograph of you and your dad from the ‘80s. Which is to say: There’s all this stuff that you get surprised by along the way, and some of that ends up mattering too.

To give an example: I knew I wanted to include a scene about the first time I taught after my daughter was born, when she was about six months old. What I wanted to write about (the set of keys I was looking for) was a certain sense of tension between a moment that had happened in the class—where I’d essentially told a student that no experience is boring, any experience holds meaning if you ask the right questions of it—and then this moment on the trip home, where my daughter was riding in the carrier on me, and she took this huge shit, and we had to sit in her shit together forever because the flight was delayed on the tarmac. And I remember sitting there thinking, “Huh, I wonder if every experience really is interesting.” I knew I wanted to write this tension between the wisdom that I’d offered the student and this lived experience that I’d had, which is also one of the tensions that’s throughout the book, between the story of experience and then the actual grittier, harsher, messier texture of lived experience. Like this version of life as a terrain you can move through, excavating meaning at all times, versus an awareness that maybe this just happened and it doesn’t mean anything.

LD: Maybe you’re just covered in shit.

LJ: Right! But then when I went back into that scene, I found some other stuff waiting for me there. For example, the fact that I’d been afraid of not feeling entirely present with my students because I was gonna feel always like my attention was still somewhere else, with my daughter. But actually I realized that something close to the opposite was happening, this desire to be hyper-present with them to justify the time away from her and make it worth something. So that emotional pivot was waiting for me, and then the awkward embodied experience of shifting roles, going from nursing to teaching. So part of what I love about scene-building is that it does feel like a mixture of intentionality and surprise, where you have some role you want the scene to play but then it also teaches you something.

LD: The level of self-awareness was so striking throughout—an awareness of your own flaws and culpabilities and contradictions. Do you have practices or anything that you do while writing to push that awareness further and find that truthfulness?

LJ: My early personal writing leaned so far towards certain kinds of self-recrimination that I had to learn how to lean away from it—that I couldn’t always make myself look bad. Because that’s just as false as a writer trying to always make herself look good. Nobody is just one thing. The god I feel like I’m always trying to serve is the god of complexity, so I think to the question of self-awareness, I’m always just trying to turn the screw a few more degrees to acknowledge how many different things were true at once. I don’t think anyone ever does anything for just one reason, so I ask “What were all the reasons?” Like yeah, I did it because I cared about that person, but also, I did it because I wanted to feel like a person who cares about that other person. And my youthful self would have arrived at the more sinister motivation and been like “Yes, that’s the truth!” but now I’m more like “Yes and, yes and, yes and.”

LD: I was thinking a lot about how this book in conversation with other memoirs about motherhood. Do you have favorite books about motherhood? Are there things that you’ve noticed that feel missing or over emphasized?

LJ: I love the way Deborah Levy writes about motherhood in her memoirs Real Estate and The Cost of Living—it’s wry and tender at once, not precious but real; she takes her daughters seriously and often gives them the best lines—and the way Nathalie Léger reckons with her own mother in her trilogy The White Dress, Suite for Barbara Loden, and The White Dress. My book is definitely engaging with the figure of the art monster from Jenny Offill’s Dept. of Speculation, and I felt so energized by how she writes about parenting in that novel and in Weather: She pays attention to particular moments, and lets many things be true at once.

LJ: I love the way Deborah Levy writes about motherhood in her memoirs Real Estate and The Cost of Living—it’s wry and tender at once, not precious but real; she takes her daughters seriously and often gives them the best lines—and the way Nathalie Léger reckons with her own mother in her trilogy The White Dress, Suite for Barbara Loden, and The White Dress. My book is definitely engaging with the figure of the art monster from Jenny Offill’s Dept. of Speculation, and I felt so energized by how she writes about parenting in that novel and in Weather: She pays attention to particular moments, and lets many things be true at once.

For me, one of the most tender threads in Splinters is about godmothers—my daughter’s godmothers—and if the book itself had a godmother it would absolutely be Elizabeth Hardwick’s Sleepless Nights. Not only because it’s a divorce narrative in disguise (she brilliantly describes shared possessions as “steeped in the conditional”) but because of its form—its short, jagged, searing icicles of prose. In fact, the earliest draft of the manuscript was called “Revision Enters the Heart,” from a line in Sleepless Nights that I quote: “Don’t you see that revision can enter the heart like a new love?”

For me, one of the most tender threads in Splinters is about godmothers—my daughter’s godmothers—and if the book itself had a godmother it would absolutely be Elizabeth Hardwick’s Sleepless Nights. Not only because it’s a divorce narrative in disguise (she brilliantly describes shared possessions as “steeped in the conditional”) but because of its form—its short, jagged, searing icicles of prose. In fact, the earliest draft of the manuscript was called “Revision Enters the Heart,” from a line in Sleepless Nights that I quote: “Don’t you see that revision can enter the heart like a new love?”

LD: Lastly, I’m gonna ask a twist on the memoirist’s most hated question—I’m not going to ask you what your ex-husband thinks of the book. But I am curious if imagining your daughter someday reading the book feels different from the usual memoirist anxiety about people in your life reading your work.

LJ: I have spent a lot of time imagining my daughter someday reading the book, and a lot of emotional energy reminding myself that I can’t know what she will think of it. I have a practice of sharing manuscripts with people who are in them whenever I can, and obviously I can’t go forward in time and share this book with a 15-year-old version of my daughter, but that process has taught me that people just never react the way you expect. It’s such a good reminder that you can’t predict or control other people’s reactions. It’s taught me that I really don’t know what she’ll make of it, and also that what she makes of it at first might be different from what she makes of it over time.

That said, I feel much clearer on my hopes for what the book will mean to her. I really wanted to write it as a love letter to her, trying to show her how she changed the world for me. And I wanted to offer her another version of her own origin story that wasn’t just a painful story about divorce, but a story of how she came into the world that also holds a tremendous amount of beauty.