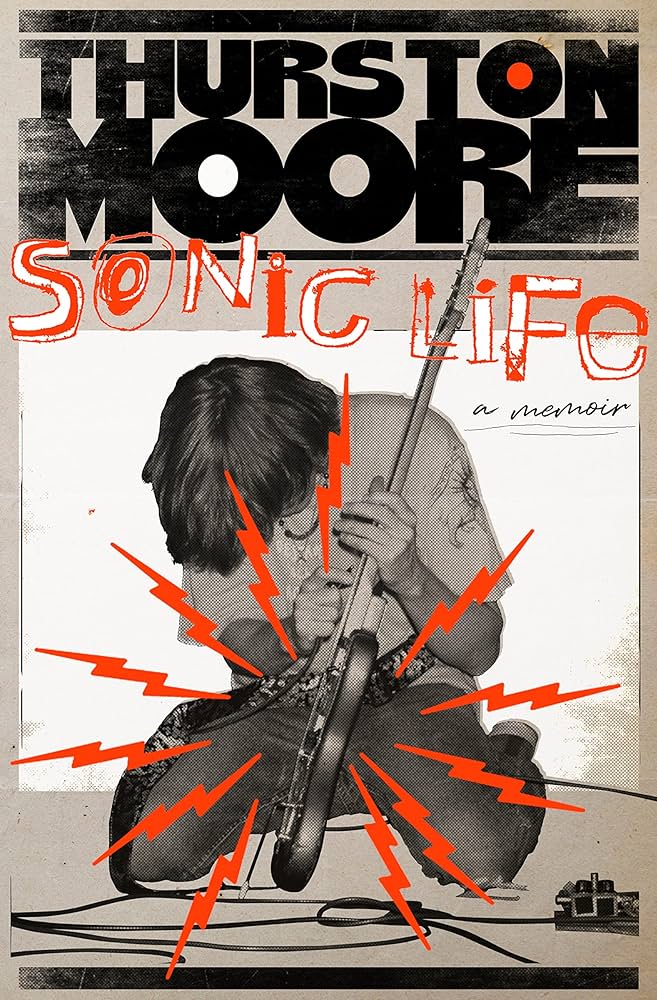

For three decades, Thurston Moore helmed Sonic Youth, a band that was intimately linked to that historic, shape-shifting milieu of art and music that once emanated from downtown New York. But in the decade since the band’s dissolution, Moore has not lessened his musical output. Sonic Life, his newly published memoir, is a fascinating chronicle of music, art, life on the road—and a vanished New York City.

Richard Klin: The range of musical influences you cite in Sonic Life are surprisingly eclectic, spanning hip-hop, Kiss, and the John Thompson piano book.

Richard Klin: The range of musical influences you cite in Sonic Life are surprisingly eclectic, spanning hip-hop, Kiss, and the John Thompson piano book.

Thurston Moore: I think it was defined by the household I grew up in, having a father who was a university professor, who had a library of books—esoteric philosophy, religious studies, music studies. He was playing the piano all the time. I just thought every house was like this. When I was old enough to have playdates and you would go over to somebody else’s house and hang out, at first I remember being concerned that these houses were empty! They didn’t have art on the walls, they didn’t have a piano, and they didn’t have books, and there was no stereo. And if there was, it was kind of the lamest-quality stuff. It was all about the TV being on all the time and frozen dinners.

And so I thought, “We’re different!” I realized that our house was about this culture of literature and music. And I embraced it. I think it allowed me to not only romanticize it, but to mythologize it; to have it be a defining aspect of my own sensibilities.

I certainly never felt that I kicked against it or revolted in any which way. If I did revolt, as any child will do in their family, it was probably against what was considered appropriate, such as Beethoven and Bach. I was into this more marginalized music, like Stockhausen or John Cage.

In the book I talk about being attracted to the more subversive signals that were coming out of the cultural margins and why that resonates to people such as us. I don’t think I ever answered that question. Maybe a lot of it is in resistance to what is considered the familiar. The otherness is more curious, more interesting, more thrilling. Seeing a photograph of Iggy Pop standing on the hands of an audience, spray-painted silver—in some ways it’s more curious and mysterious than, say, just another picture of Rod Stewart. As beautiful as Rod Stewart is [laughs] and as much as I liked the Faces. But I didn’t know what the Stooges sounded like—you didn’t go down to the mall and find Stooges records. You had to search them out. It has something to do with searching for these obscure relics. And then they’re so shocking when you hear them. They’re not like anything else out there. They become your friends that your other friends don’t really associate with.

RK: There’s a line in the book that really resonated: “Sonic Youth, it turned out, was all about fun, music, art, absurdity—life.” Sonic Youth was power and loudness, but there was this delicate beauty embedded in the music.

TM: It was very purposeful from day one to have this balance between discord and beauty. And there’s beauty in discord. I talk about playing with [composer] Glenn Branca and I recall one of his compositions—The Ascension —falls into this moment of the guitars that are consistently raging in discord, into this beautiful, magical moment. And I thought, What a great relationship that is to have these things coexist. Those are our realities; those are our dichotomies of light and dark. Even though we never really articulated this as young people in our early 20s, I think that was something that we realized was a strong musical statement to make: Beauty coexisting with these larger, darker discordant moments. We became more attuned to investigating beauty as we became more sophisticated players.

—falls into this moment of the guitars that are consistently raging in discord, into this beautiful, magical moment. And I thought, What a great relationship that is to have these things coexist. Those are our realities; those are our dichotomies of light and dark. Even though we never really articulated this as young people in our early 20s, I think that was something that we realized was a strong musical statement to make: Beauty coexisting with these larger, darker discordant moments. We became more attuned to investigating beauty as we became more sophisticated players.

One thing that appealed to us as a band was to make music that was primarily uplifting. That was always important, even when investigating darker and more nihilistic aspects of culture. It was creating music that was uplifting in its engagement. As an experimental music band, we felt like we could really investigate that without it being rote or using the same tropes everybody else was using. It was fun—it was always fun. The idea of putting different implements on our guitar strings and changing the tunings—there was something academic about that and studious, but it was also essentially really fun to do that. It was fun because it was audacious.

RK: What was the intent behind Sonic Life?

TM: For me, writing is such a joy and I’ve always thought of myself as a writer. I’ve published and edited and written poetry for years—I published a poetry journal; I teach a writing class at Naropa University. I’ve always been very engaged with literature, but it’s never had the profile of what I do with music, obviously. I always harbored a desire to write a book-length text. I knew the easiest device was to write a memoir at this point. It was to be mostly about music essaying within the confines of a memoir. It allowed me to actually just write.

I knew that I wanted to write this book just to be in the joy of writing and get into the art of writing. Everything about it—even getting into a whole year of editing—I enjoyed that immensely. The practice of editing a long manuscript was as joyful as it was writing it. The construction of the book, the publishing of it—these are all things I really love. For me, that was pretty much how I wanted to get my feet wet with all this.

RK: The book is also very funny in places.

TM: There are some funny moments. It’s how to turn a phrase to keep that humor in check. It’s written in the voice of a 65-year-old, but I’m mostly writing about a time when I was in my 20s. I didn’t have that voice then—I was actually a very snarky, thinks-he-knows-it-all kind of brat! I couldn’t really write in that voice! So there is this modicum of mythologizing going on when you’re writing a memoir. You’re giving a more sophisticated voice to people who weren’t exactly that. There’s a certain level of fiction that’s going into the nonfiction. I was okay with that, because I realized that’s kind of how it works.

It was interesting to try to find a balance there. And there were certain things that were humorous that I took out of the book or didn’t write about, because they might have been humorous to me then, but it’s a bad look now. Mainly, some kind of exploit that was predicated upon being inebriated. It’s not cool to talk about. Or not even myself—somebody else of note you might know about, an incident that happened—I don’t think that person would appreciate you talking about them. Even though it was funny and it was 30 years ago! Maybe I should ask permission first—or not at all.

RK: The idea of “sonic democracy” is a crucial point in the book.

TM: It’s a phrase that stuck with me when I came across it a couple of years ago. I lifted it from a great contrabass player named Luke Stewart—and he came up with that phrase about a recording he did: a sonic democracy at work in the studio. That’s such a great phrase! It has the word sonic in it; it extols everything about how we looked upon ourselves as a band. It’s such a beautiful thing to say about any kind of collective that presents itself as a collective forum to begin with.

Certainly Sonic Youth had the dynamic where different people brought in different energies to the group. And at some point I remember addressing, Why did the other three members get the same credit for the lyrics that I’m writing? And I was writing the motherlode of lyrics on these records. Because all the songs are credited to Sonic Youth, as opposed to music by Sonic Youth, lyrics by Thurston Moore—or whatever; breaking it down. And Steve Shelley, the drummer, straightened me out: “The band exists as a forum for us all to work together as a collective. What I write on my cymbals, with my drumsticks—those are my lyrics.”

He was absolutely correct. And I fell more in love with the socialism of it. And I read an interview with Wayne Kramer of the MC5, where he said, “Our first two records, we had this political idea that all music was by the MC5. And we didn’t break it down to who wrote what. On our third record, we broke it down and started taking specific song credit. And that was the end of the group.”

It broke into the collective vibe. I took that to heart as well. I always loved that Sonic Youth was a sonic democracy.