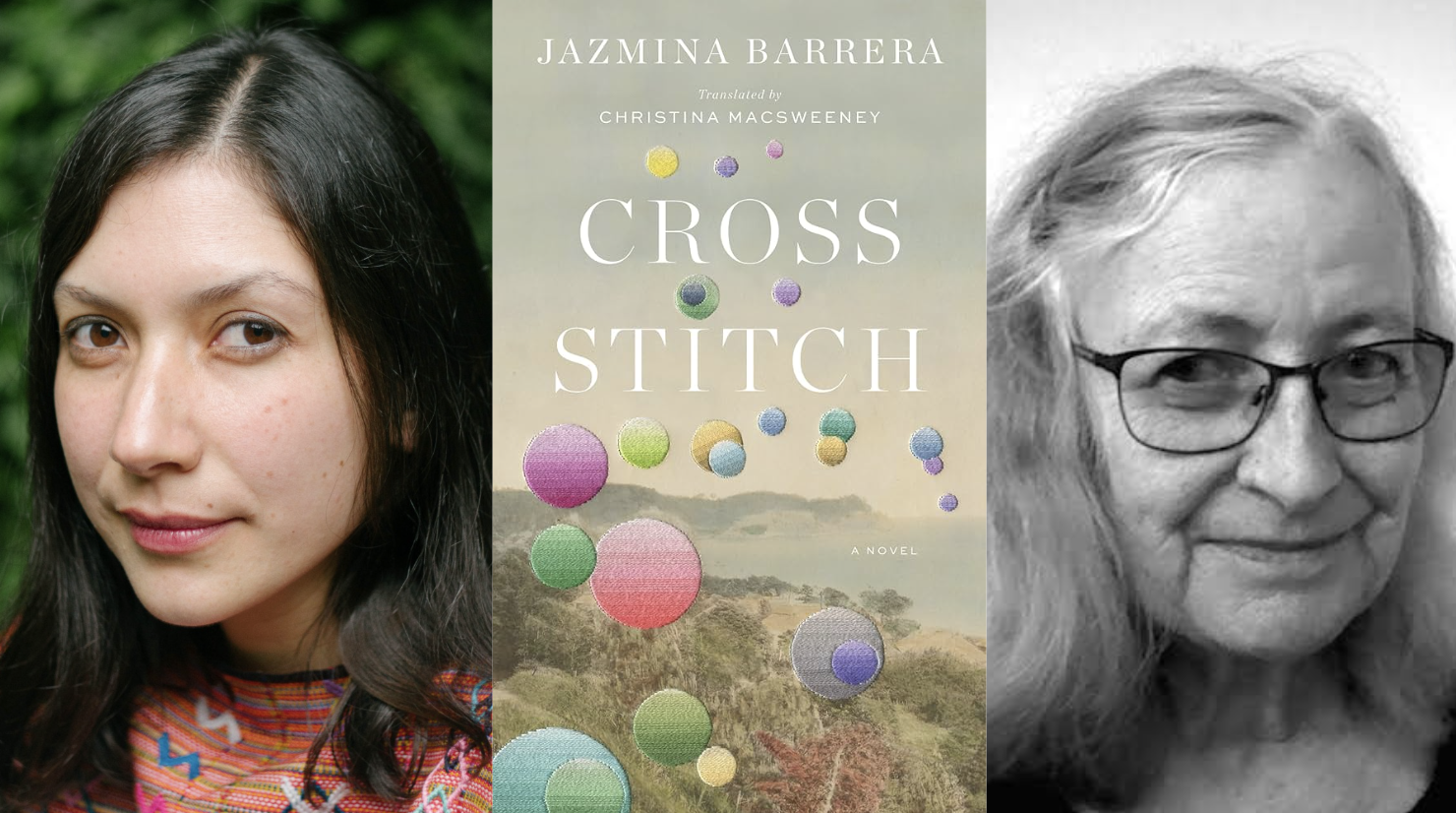

Author Jazmina Barrera and her longtime translator, Christina MacSweeney, have been pen pals for years. I asked them to exchange some letters, as they are wont to do, about friendship, translation, and their new novel Cross-Stitch. —Sophia Stewart, editor

Author Jazmina Barrera and her longtime translator, Christina MacSweeney, have been pen pals for years. I asked them to exchange some letters, as they are wont to do, about friendship, translation, and their new novel Cross-Stitch. —Sophia Stewart, editor

*

Dearest Jaz,

I’m feeling both excited and a little worried about starting a new thread in our correspondence. In the past, our emails have always seemed to flow naturally. It’s hard to know where we should begin.

Abrazos,

Christina

Dearest,

Here’s what I think. We’ve been asked to talk about the translation of Cross-Stitch in an epistolary format. And although starting a new thread in our conversation does feel a little artificial, it’s at the same time easy because we’ve always had an epistolary relationship. Even before you became my translator, you were the first and only pen pal I’ve had who lasted more than a couple of lines. In this day and era of WhatsApp and emojis, it seems difficult, if not impossible, to have a meaningful conversation with someone through the thoughtful, time-consuming format of long letters, and yet that is just what we’ve managed to have for many years now. We’ve talked about the weather, books, travels, and gossip in this format. We’ve also talked many times about translation. They want us to write about a book that is entirely about friendship (it is also about embroidery, but the main thing about embroidery there is that it is a catalyst for friendship), and they want us to talk about translation, and I think that in our case, translation has become an important part of the friendship. How do you feel about that? Do you think that translation can enable friendship? I’ve always thought of translation as a profession of care and affection towards language and texts. Could it be a work of friendship? Maybe not always towards the author, but definitely towards the text?

I’d love to hear your thoughts on that.

Abrazos enormes,

Jaz

Dearest,

I guess I come from a generation where letter-writing—literally putting pen to paper—was a fairly common practice. In my youth, when international phone calls were still very expensive, that’s how we kept in touch with the Irish side of the family and I kept up the habit with some of my aunts and one or two cousins over the years. Plus, I’ve spent long periods living far from friends, so letter-writing was a way of maintaining those friendships.

These days that correspondence is mostly by email, which has its advantages and disadvantages. I miss the sound of an envelope dropping onto the mat and the pleasure of recognizing someone’s handwriting. Emails seem to require an immediate response, whereas snail mail allows time for rereading, for thought, time for things to happen or not happen.

When we first met briefly in New York, I felt you were a person I wanted to know better and so asked another literary pen pal (Daniel Saldaña París) to put us in touch. I hadn’t read your work then and I suppose you hadn’t read my translations, so we started our letters on a clean slate, getting to know each other better. And just like in Jane Austen’s letters to her sister Cassandra, we’ve often been serious but also seem to be able to express non-verbal laughter, smiles, mostly without emojis. Seeing your name in my inbox is almost as good as the sound of the letter on the mat.

You mention the role of correspondence in the relationship between author and translator, and that’s something I’ve thought about a lot. Not all the authors I’ve worked with have wanted to be involved beyond answering specific queries, but when it does happen, the correspondence has often grown into friendship or something approaching it, a seed of possible friendship. I don’t know how you feel about this, but for me the author/text/translator relationship involves respect and trust on both sides. As a translator, I’m being offered privileged access to a literary mind and, in the case of fiction, the characters that mind creates. The author entrusts me with something precious—the text—and it’s my job to care for it, nurture it, respect it. And I guess that as translators we also entrust our authors with something of ourselves through our understanding of their work and the ways we find to bring it into a new cultural setting. So it’s definitely a close bond and I think you’re right in suggesting that translation at its best is a work of friendship, it involves many of the things that form the foundation of friendship.

Dearest, I think that’s all for today, but I’m really looking forward to continuing this new thread and seeing where it takes us.

Abrazos muy fuertes,

Christina

Dearest,

I’ve been thinking a lot about this. I am myself translating right now a lovely essay by Amina Cain called A Horse at Night . The two previous books I translated were a collaborative work with Alejandro Zambra, and this time I really miss the possibility of conversation. There are many concrete choices to be made when you are translating, and it was so useful to have someone else’s opinion on these, to be able to decide together. It made me feel more confident, and it made the task a happier one, to be honest. Talking to myself is just not the same. So I asked a friend of mine who is also translating something, to do it together with me, to spend a couple of hours translating side by side and then have a moment of Q&A, where we both give our opinions on certain problems we have with the texts. Have you done something like that?

. The two previous books I translated were a collaborative work with Alejandro Zambra, and this time I really miss the possibility of conversation. There are many concrete choices to be made when you are translating, and it was so useful to have someone else’s opinion on these, to be able to decide together. It made me feel more confident, and it made the task a happier one, to be honest. Talking to myself is just not the same. So I asked a friend of mine who is also translating something, to do it together with me, to spend a couple of hours translating side by side and then have a moment of Q&A, where we both give our opinions on certain problems we have with the texts. Have you done something like that?

Since I wrote Cross-Stitch, I’ve come to think about friendship as a very long conversation. One where distances and intensities are constantly changing, one that has a lot of stops, and sometimes full stops as well. Translation is also a form of conversation: an actual one, with the author; an implied one, with the text; a constant one, with yourself or with the person who translates next to you; and even sometimes a conversation with someone’s ghost. So it’s easy to see how it can become a seed for friendship, as you say, or part of a friendship (like in our case) or even be the cause for the end of a friendship. Have you ever fought with a friend over a translation? I recently fell out of friendship with a translator (she doesn’t translate my books, she just happens to be a translator) and felt that our problem was precisely that: a translation problem, a lack of understanding, and the impossibility of putting into words our hurts and regrets. Silence, as the opposite of translation, as the opposite of friendship.

Abrazos enormes,

Jazmina

Dearest Jaz,

Apologies for the delay. I’ve had a lot of loose ends to tie up and wanted to wait to reply until I could give this my full attention. And just saying that to myself made me think about “attention” in relation to translation and to friendship. Both situations demand it in full and when they go wrong, it’s often because we’re imposing our own preoccupations on our understanding of the friend/text rather than accepting them as they are. And that made me think about the friendships in Cross-Stitch; it often seems to me that in some way Citlali acts as a translator between Mila and Dalia, she has the ability to mediate between them, explain them to each other. After her death, Dalia and Mila have to find ways to talk to each other and it could be their shared love of Citlali that makes their renewed conversation possible. Do you think that’s true?

I wonder if it’s possible to draw an analogy between the friendships we have throughout our lives and our reading habits: there are books I go back to again and again that are like the friends I don’t see for years but instantly know the connection hasn’t been lost; then there are those that interest me for a short time but don’t really make a deep impression, and others that seem vitally important at one point, but then life moves on and they seem less relevant or I discover things in them that weren’t apparent on a first reading and that makes them less appealing. That last situation could apply to your broken friendship, and you could think of it like a re-translation of the relationship, coming to it from a different angle.

I’m glad you’ve found it helpful to work with a friend on your latest translation, but I think we’re different in that respect. I’ve taken part in translation workshops and enjoy them as an exercise; however, when it comes to the actual practice, it’s the solitude I really love. My conversation is with the text and with myself (often speaking parts of the original and translation aloud, singing music I associate with it; the neighbors doubtless think I’m half-crazy, and they’re probably right) and then, when I’m reasonably happy with my translation, the conversation expands to include the author, copy editors, proofreaders, and readers.

That idea of the solitariness of translation also made me think of how embroidery forms the “thread” of a friendship between Mila, Dalia, and Citlati. I learned to embroider when I was quite young and loved it, but as no one else in my family circle and friends was really interested, it was something I tended to do alone. So the bond of solidarity forged by women through needlework that runs through the novel is one of the aspects I find fascinating. Do you think we can also draw parallels between “women’s work” and the act of translation? Within Western culture, both are often seen as secondary to the all-important notion of individual creativity.

I realize that, unlike our usual correspondence, I haven’t mentioned the weather yet! While the rest of Europe seems to be close to meltdown, here in Norwich it’s cool with occasional intense thunderstorms and lightning that seem to appear from nowhere and, as if they were on some urgent errand, hurry off to another place.

Well, my dear, I’m looking forward to seeing your email in my inbox again.

Until then, take care and I send huge hugs,

Christina

Dearest,

Where to begin. Your idea about comparing translation to embroidery and other underrated women’s work seems very appropriate to me. One of the things I understood while doing research for Cross-Stitch is that embroidery holds a very different relationship to the concept of originality than other more canonic forms of art. Because it was not considered art for so long, embroidery could forget about this obsession with the new and create a freer dialogue between tradition and innovation. Women exchanged patterns, copied them, reproduced millenary symbols and techniques and or invented new ones whenever they felt like it. They translated old designs into new materials, and new ideas into old stitches. Just as translation, it’s a form of art that has less prestige but no less potential for creativity. Both seem to me to be different kinds of handcraft (instances where technique meets imagination and where hands are involved) and they both seem to understand that it’s in the subtleties, the details of an apparently mechanical task that aesthetic decisions of the most important kind are made. They both can thank that lack of prestige for pushing away expectations that can put a terrible strain on creation.

I love to think about Citlali as the translator between Mila and Dalia. She most definitely was. And yes, without her they have to find a way of speaking a similar language, which very well could be embroidery.

Dearest, I realize now something else about our correspondence: it is the only instance I have in which I get to write in English. As you know, I studied English Literature and I have a special love for that (this) language, for its Anglo-Saxon music, its staccato rhythm, and its writers. I used to write all of my papers for college in English, but since then my literary writing has been done entirely in Spanish. Writing to you allows me to play with words I love that I never get to play with, and also to feel like I’m 19 years old again (19 was a very good age for me).

I believe we’ve already crossed the maximum word count here! So I’ll say goodbye now with a note about the weather: I’m leaving Lima today (this is my third time in Perú, but only my first time in Lima), and found the weather fascinating. There is one perpetual cloud covering the entire sky (not fog, at least not right now, because the cloud is higher) but it almost never rains. They call the sky a “panza de burro” (donkey’s belly?, tummy?), but since the sky is concave, one would think that the city is inside and not below the donkey’s belly.

¡Abrazos, querida!

Jaz