I will never forget the first time I saw the devil—leering at me, lurking in the corner of the room, glowing red and approaching my motionless body. I was caught between sleep and waking; I blinked furiously; I struggled to rouse my heavy limbs as he raised his hand to my face. I could not even muster the strength to open my mouth and cry out, help, mommy, help, the monster will get me—

In the weeks that followed this first encounter, I discovered an online community of survivors who documented their experiences with sleep monsters and demons. I remembered it as one of those rare, significant encounters in the region of the mind where reality and fantasy, literature, dreams, and the occult coexist, but the commenters taught me that doctors had a term for our episodes (sleep paralysis) and a hypothesis that the monsters at night were hallucinations caused by irregular sleep and lack of sleep. Maybe sleep, I thought sadly, had been classified and pasteurized like all the other great human mysteries. I had not escaped the grasp of the antichrist; I had bad dreams.

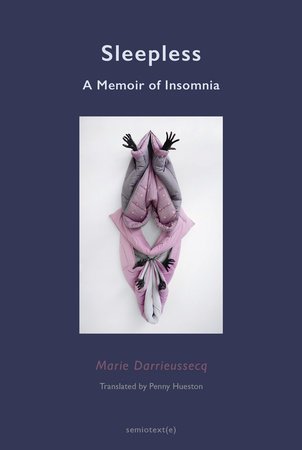

I could not stop myself from constructing a story of my life through sleepless nights as I read Sleepless, Marie Darrieussecq’s strange, beautiful meditation on the horror and valor of insomnia. “This book is the result of twenty years of panic” that began with motherhood, writes Darrieussecq. “As my children learned to sleep, I unlearned.” Across 255 pages she attempts to learn again, consulting with physicians, downing barbiturates, and dwelling on the vast literature of sleep and sleeplessness. The author adopts such varied and inventive perspectives on her theme that I began to care less about the resolution to her woes than I did about the writing itself. And the dark art of writing, she suggests toward the end of her lyrical journey, might make her free: “Exorcism: when I have put the final full stop at the end of this book, my eyelids will grow heavy. A spell. A potion. My insomnia will dissolve in this book. The book will save me. When I hold the printed version in my hands, I will fall asleep.”

The expansion of social media and the “wellness” market have made sleep a $500 billion industry in the U.S., spawning sleep tracking rings, relaxation headbands, sunrise alarm clocks, weighted blankets, guided meditations, guided journals, podcasts, too many boxed mattresses, too many tracking apps, too many books declaring The Sleep Revolution, explaining Why We Sleep, teaching The Science of Sleep, and promising, at long last, The Sleep Solution. These books, like most pop-science bestsellers, read like they were written by the same algorithms, as they each present the facts, survey the trends, make puerile jokes, and cajole the reader into personal resolution. By contrast, Sleepless might be one of the few original interventions on the topic in the past 15 years, making the expert volumes sound quaint and even ignorant in how they lack the experience and poetry of the night.

The expansion of social media and the “wellness” market have made sleep a $500 billion industry in the U.S., spawning sleep tracking rings, relaxation headbands, sunrise alarm clocks, weighted blankets, guided meditations, guided journals, podcasts, too many boxed mattresses, too many tracking apps, too many books declaring The Sleep Revolution, explaining Why We Sleep, teaching The Science of Sleep, and promising, at long last, The Sleep Solution. These books, like most pop-science bestsellers, read like they were written by the same algorithms, as they each present the facts, survey the trends, make puerile jokes, and cajole the reader into personal resolution. By contrast, Sleepless might be one of the few original interventions on the topic in the past 15 years, making the expert volumes sound quaint and even ignorant in how they lack the experience and poetry of the night.

Rather than well-reasoned advice, Darrieussecq begins with the unknown. In her description, “insomnia has no ‘theme’” and “nothing prevents the insomniac from not sleeping”; “‘real’ insomnia does not care in the slightest about objective causes.” She contrasts those who “rest their head on the pillow and off they glide, hurtling down the slope” with “we insomniacs,” who “plummet into horrendous ravines and the bags under our eyes are bruise colored.” For this sleep-writer, insomnia is an infinite torture, a “Möbius strip” with “the single-sided, single-edged surface continues unendingly, looping back on itself.” With the impossibility of escape, Sleepless becomes a book of searching.: “Hidden in our attics, crouching beneath our mattresses, sliding between the joists of time, where does insomnia come from? From ghosts? From the brain? From a troubled soul? From the world?” “Oh, my insomnia, what plan are you following? Do we need to marshal this huge turmoil of ghosts?” “How can you want the thing that should be taken for granted?”

Like many of the book-length essays published by Fitzcarraldo in London, Sleepless explores a theme in short, resonating fragments or vignettes. Darrieussecq surveys the “champions of fatigue” in literature: Proust, Duras, Kafka, Cioran, Kawabata, Alix Cléo Roubaud. She reads texts about insomnia but also teases the insomnia out from unexpected texts (“literature is all about lost paradises and insomnia”). She seeks understanding in anecdotes about the sleep of soccer players, world leaders, and celebrities who “have ended up dead in the hope of sleeping.” She goes on a “world tour” of literary encounters with sleeping pills; she writes about ghosts, rituals, books that converse with one another on shelves. We find the devil here, too: “[T]he monster comes when we’re asleep.” She writes to us in her deprivation: “As the night is pulverized, it grinds me up. I am kneaded into the material from which black holes are made, I dissolve in the antimatter of the underside of the world.” Darrieussecq tries sleeping pills (“I’ve been running on barbiturates for almost thirty years […] I stagnate on sedatives, I’m hypnotic with narcotics”), alcohol (“sometimes alcohol helps me to live. Alcohol helps me to sleep”), an acupressure mat (“it’s extremely painful”), sleeping in separate beds (“Let’s clarify the idea of living as a couple”), and, perhaps as a final resort: “I’ve tried metaphors.” Montaigne-style, Darrieussecq reaches for quotations and new subjects with every paragraph in an exploration of her theme, making Sleepless a book of epigraphs, both found and produced, and giving the effect of her voice being just one within the great ongoing chorus on sleep and our search for its safe confines. Through this wide range of subjects and tonal registers, Penny Hueston’s translation animates Darrieussecq’s style in English and maintains the sound of her voice.

Darrieussecq’s approach places her in the tradition of Polish writers such as Wisława Szymborska, whose whimsical, creative conceits on familiar topics build to philosophical stances on how to be, and Olga Tokarczuk, whose narrators look from the outside to uncover resonances among known things. Darrieussecq arrives at the existential implications of sleep and sleeplessness while she avoids manipulating space breaks for a quasi-profound tone that makes most contemporary literature nearly unbearable to read (at least to me). Her prose stops and starts in sentences, like telegram dispatches, scribbled with frenetic vigor. This book is a trance. Darrieussecq’s language is like a nightmare: alive.

Darrieussecq does not linger in her indulgence of literature, film, and the poetry of her condition, as she considers sleeplessness for undocumented and homeless people. At one point she describes her presence at migrant camps as “the foreigner, uneasy, arriving in order to leave, to write a story about it,” and she might have engaged more with the ethics of her writing. The final act of the book moves into a defense of animals and a consideration of the waking nightmare of animal cruelty, engaging with Aldo Leopold’s Sand County Almanac and the protagonist of Tokarczuk’s Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead. “Sleep is a bridge between species,” Darrieussecq writes, and she suggests a connection between the societal loss of sleep and our movement into restless consumption, slaughter, and destruction. She takes on direct facts about the loss of species as well as more mystical perspectives, writing that “in equatorial forests, trees are insomniacs. […] [W]e cut down these thousand-year-old forests and insomnia spreads. The trees release it throughout the world like an evil gas, and we are being asphyxiated.” The playful conceit that “the insomniac is noble; only idiots sleep,” becomes an ethical stance: Butchers sleep while insomniacs cannot close their eyes to the crimes of their species. Darrieussecq succeeds with her advocacy because she does not shout her morality at the reader: Her book murmurs for “awakenings,” changes “to wake up slightly different.”

Darrieussecq does not linger in her indulgence of literature, film, and the poetry of her condition, as she considers sleeplessness for undocumented and homeless people. At one point she describes her presence at migrant camps as “the foreigner, uneasy, arriving in order to leave, to write a story about it,” and she might have engaged more with the ethics of her writing. The final act of the book moves into a defense of animals and a consideration of the waking nightmare of animal cruelty, engaging with Aldo Leopold’s Sand County Almanac and the protagonist of Tokarczuk’s Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead. “Sleep is a bridge between species,” Darrieussecq writes, and she suggests a connection between the societal loss of sleep and our movement into restless consumption, slaughter, and destruction. She takes on direct facts about the loss of species as well as more mystical perspectives, writing that “in equatorial forests, trees are insomniacs. […] [W]e cut down these thousand-year-old forests and insomnia spreads. The trees release it throughout the world like an evil gas, and we are being asphyxiated.” The playful conceit that “the insomniac is noble; only idiots sleep,” becomes an ethical stance: Butchers sleep while insomniacs cannot close their eyes to the crimes of their species. Darrieussecq succeeds with her advocacy because she does not shout her morality at the reader: Her book murmurs for “awakenings,” changes “to wake up slightly different.”

At the end of this book and this review, like with every other, we must ask the ultimate question: Is there transformation? I finished Sleepless last night and woke today slightly different—more pensive, as the book’s images and voice lingered on the edges of my thoughts. Darrieussecq writes that “poetry, like dreaming, speaks a wild truth.” Books like Sleepless continue the project of great literature, and if enough speak into the ears of readers perhaps, after ages, we will observe transformation in our ways of looking on the world and in our conduct with the nonhuman. But maybe for the insomniac, the true sufferer at the clutches of unseen demons, the witness to nighttime and daytime horrors, there is no answer—only the future approaching from the corner of the room; only complaint, desperation, literature.