The British travel writer and novelist Bruce Chatwin held that there are two categories of writers: “the ones who ‘dig in’ and the ones who move.” “There are writers who can only function ‘at home,’ with the right chair, the shelves of dictionaries and encyclopedias, and now perhaps the word processor,” he observed. “And there are those, like myself, who are paralyzed by ‘home,’ for whom home is synonymous with the proverbial writer’s block, and who believe naïvely that all would be well if only they were somewhere else.” I like this notion. It seems to have an air of true insight about it. When I read Chatwin, for instance, I detect the shuffle of his restless feet traversing ancient causeways, just as, when I read Melville, I smell salt air.

One might think that we better know the writers who “dig in” than those who “move.” That is to say, we can picture them at their desks, in their studies, working. Proust’s cork-lined room and the bed in which he composed his masterpiece affords one an imaginative notion of the writer’s interior world, if not the creative effort itself. Place matters to the imagination. I have frequently, while traveling, attempted to enhance my reading imagination by linking favorite writers to place. Once, for instance, while in London traipsing around Bloomsbury, I sought out Virginia Woolf’s home. The expected brass plate bolted to the building corner confirmed the find. But the house is not open to the public, and is now converted office space. I was reduced to peering in through a barred street window. There were computers and furniture, a woman in a beige sweater pounding away on a keyboard and the flurry of activity one associates with commerce. I tried to imagine Woolf there but failed—a “dug in” writer who slipped through my fingers. The failure was particularly poignant in light of her famous observation, “A woman is to have money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction.”

Likewise, I once made an effort to find Gertrude Stein’s Paris house, her salon at 27 rue de Fleurus, the place she shared with Alice B. Tolkas. Also not open to the public. Stein called Alice “Pussy” and Gertrude was “Lovey.” There is that awful scene in A Moveable Feast, where the young Hemingway, standing in the foyer of Miss Stein’s house, overhears her upstairs: “Then Miss Stein’s voice came pleading and begging, saying, ‘Don’t, pussy. Don’t. Don’t. Please don’t. I’ll do anything, pussy, but please don’t do it. Please don’t. Please don’t, pussy.’” She was dead 18 years when Hemingway’s memoir of being hungry in Paris was published. Of his writing, Miss Stein said, “Hemingway’s remarks are not literature.” I did not so much think of that passage while standing at the front door, as feel the lapsed presence of so many with such promise, Gertrude’s Lost Generation. Hemingway, likewise, is nowhere to be found at his Key West home, despite its well-preserved museum condition. I suspect his spirit has been trampled by the hoards of tourists over the years. Papa was plagued by their presence and had bricks shipped from Baltimore, where they’d been taken up from newly paved streets, to construct a wall around the place, protecting his privacy. His famous five-fingered cats, however, remain in abundance.

Likewise, I once made an effort to find Gertrude Stein’s Paris house, her salon at 27 rue de Fleurus, the place she shared with Alice B. Tolkas. Also not open to the public. Stein called Alice “Pussy” and Gertrude was “Lovey.” There is that awful scene in A Moveable Feast, where the young Hemingway, standing in the foyer of Miss Stein’s house, overhears her upstairs: “Then Miss Stein’s voice came pleading and begging, saying, ‘Don’t, pussy. Don’t. Don’t. Please don’t. I’ll do anything, pussy, but please don’t do it. Please don’t. Please don’t, pussy.’” She was dead 18 years when Hemingway’s memoir of being hungry in Paris was published. Of his writing, Miss Stein said, “Hemingway’s remarks are not literature.” I did not so much think of that passage while standing at the front door, as feel the lapsed presence of so many with such promise, Gertrude’s Lost Generation. Hemingway, likewise, is nowhere to be found at his Key West home, despite its well-preserved museum condition. I suspect his spirit has been trampled by the hoards of tourists over the years. Papa was plagued by their presence and had bricks shipped from Baltimore, where they’d been taken up from newly paved streets, to construct a wall around the place, protecting his privacy. His famous five-fingered cats, however, remain in abundance.

I went to Prague seeking Kafka, but he too had disappeared. The City of a Thousand Spires, however, remained true to a fashion and I gave myself to its dark alleys and endless cobblestone streets while intoning the spirit of the writer who, perhaps more than any other, ushered us into the modern era. Though Prague invites an exercise of such transmutations, to this pilgrim the city is more given to music. Smetana and Dvorak are easier to find than the man of The Castle. I do not think this unusual as music, once released abides ripe in the atmosphere, whereas the written word must be sought out. Regardless, as Kafka said, “Prague doesn’t let go.”

I went to Prague seeking Kafka, but he too had disappeared. The City of a Thousand Spires, however, remained true to a fashion and I gave myself to its dark alleys and endless cobblestone streets while intoning the spirit of the writer who, perhaps more than any other, ushered us into the modern era. Though Prague invites an exercise of such transmutations, to this pilgrim the city is more given to music. Smetana and Dvorak are easier to find than the man of The Castle. I do not think this unusual as music, once released abides ripe in the atmosphere, whereas the written word must be sought out. Regardless, as Kafka said, “Prague doesn’t let go.”

The spirit of Joyce is to be found in Dublin, though ironically he wrote in self-exile. Thoreau’s cabin at Walden is lost to history, but Emerson’s house in Concord, purchased in 1835, remains, now a museum, and it is easy to imagine the great man dug in, to use Chatwin’s phrase, surrounded by his books and working intently. The house contained, Emerson declared, “the only good cellar that had been built in Concord.” Exploring Ireland a few years ago, north of Sligo, I happened across the grave of W.B. Yeats, inscribed with the last verse of Under Ben Bulben:

Cast a cold eye

On life, on death.

Horseman, pass by!

All this is a way of working round back to Chatwin’s observation that there are writers who dig in and writers who move. I did not find the writers I sought. The men and women who had dug in did not remain, but for the Sage of Concord. Even in my once-hometown of Portland, Maine, the spirit of Longfellow is not found at his restored museum-home, but rather at the outlook at Portland Head, Cape Elizabeth, where he would sit and watch the restless ocean break over the granite coast.

The peripatetic writers—the ones who “move”—should naturally elude us, their scent long ago extinguished. I would expect that. But instead, perhaps for this very reason, because they did not dig in, they are more ready instruments of the imagination. While traveling through India I came to rest in the village Rohet, in the state of Rajasthan. It was in the garden after a hot day of travel that I sat and opened my Lonely Plant Guide to Rajasthan. Rohet warrants just one short paragraph in the current guide. It is devoted to a brief description of Rohet Garh, a 350 year-old manor, now a heritage hotel. And in that single paragraph one sentence lit me afire: “Bruce Chatwin wrote The Songlines here.” Parenthetically, the guide offered the room number: 15. I was staying at hotel Rohet Garh. I looked across the garden. A peacock posed against a hedge. Behind the hedge, there were stairs and at the top of the stairs, room 15.

The peripatetic writers—the ones who “move”—should naturally elude us, their scent long ago extinguished. I would expect that. But instead, perhaps for this very reason, because they did not dig in, they are more ready instruments of the imagination. While traveling through India I came to rest in the village Rohet, in the state of Rajasthan. It was in the garden after a hot day of travel that I sat and opened my Lonely Plant Guide to Rajasthan. Rohet warrants just one short paragraph in the current guide. It is devoted to a brief description of Rohet Garh, a 350 year-old manor, now a heritage hotel. And in that single paragraph one sentence lit me afire: “Bruce Chatwin wrote The Songlines here.” Parenthetically, the guide offered the room number: 15. I was staying at hotel Rohet Garh. I looked across the garden. A peacock posed against a hedge. Behind the hedge, there were stairs and at the top of the stairs, room 15.

I used to find Chatwin a difficult go. I took In Patagonia with me the first time I went to, well, to Patagonia. And although I read it, it did not come easily. I re-read it on a return trip two years later and like many good books it gave up a bit more the next time around. I find his style now welcoming and accessible, lending credence to my observation that there are right times and wrong times to pursue an author.

I used to find Chatwin a difficult go. I took In Patagonia with me the first time I went to, well, to Patagonia. And although I read it, it did not come easily. I re-read it on a return trip two years later and like many good books it gave up a bit more the next time around. I find his style now welcoming and accessible, lending credence to my observation that there are right times and wrong times to pursue an author.

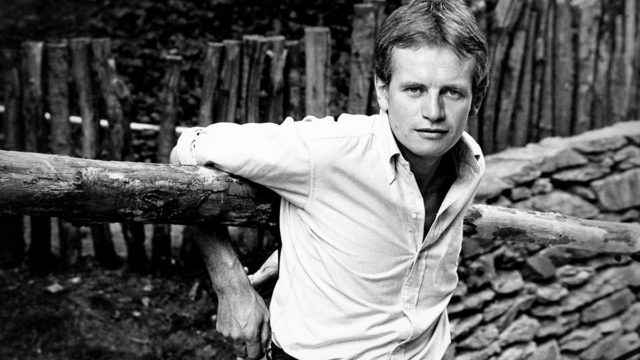

Chatwin is an interesting study. Known not only for his writing, Chatwin is Chatwin because of the life he carved out and promoted. Like Hemingway, he was known as much for his peripatetic life as his writing. I find this appealing beyond resistance, as I don’t so much read a book as co-construct the reading experience with the writer’s existence. I know this is an inappropriate approach to a “text” in some circles and therefore I do not travel in those circles. That the writing life is as much a curiosity to me as the text is edifying, a connection prefer to reinforce, not deconstruct.

Back to Chatwin in India. Room 15 was occupied the day I arrived. I kept my eye on it and the next morning it was open for cleaning and empty of guests. I crept up the side stairs and went in as the maid was changing the bed. It was larger and more elegant than my room and I imagined myself spending time here, perhaps months. The sun shone in through a large three-pane window. I could do this, I thought, thoroughly kidding myself. I could stay here and forget the world and write and be productive, happy even. “I adore it here,” Chatwin wrote of Rohet. “Lunch yesterday, for example,

consisted of a light little bustard curry, a puree of peas, another of aubergine and coriander, yoghurt and a kind of whole-meal bread the size of a potato and baked in ashes. A sadhu with a knotted beard down to his kneecaps has occupied the shrine a stone’s throw from my balcony; and after a few puffs of his ganja I found myself reciting, in Sanskrit, some stanzas of the Bhagavad Gita. I work away for eight hours at a stretch, go for cycle rides in the cool of the evening, and come back to Proust.

“A cool blue study overlooking the garden,” Chatwin wrote to a friend about room 15. “A saloon with ancestral portraits. Bedroom giving out onto the terrace. Unbelievably beautiful girls who come with hot water, with real coffee, with papayas, with a mango milkshake. In short, I’m really feeling quite contented. The cold and cough has been hard to shake off. A dry cough always is. But thanks to an ayurvedic cough preparation, it really does seem to be on the wane.”

Chatwin was ill during this stay in India. He would die three years later from complications due to HIV. Songlines was finished north of here, near the Nepalese border. I asked the manager if there was anyone around who might remember Chatwin’s stay. “That would be the owner,” he said. I presumed he meant the Thakur, or the Rajasthani gentleman of the Champawat clan upon whom the fiefdom of Rohet had been bestowed in 1622. Regrettably, the gentleman never appeared.

Seeking Chatwin’s footsteps I visited a nearby Bishnoi village the next morning. It was early and the sun was still low on the horizon. The village walls were painted blue. A morning religious ritual, with opium as the instrument of sacrament, was beginning—again. The village elders had already enjoyed one devotional ceremony that morning and were anticipating the next. They ushered me around a wall and begged me to sit. An elder with a short gray beard welcomed me, pressing his palms together. He had glassy, red-rimmed eyes and sported a Cheshire cat grin. Opium is not smoked here, it is drunk, prepared like coffee. Water is filtered through it, turning it a brown-amber; then it is poured into the palm of the elder. An assistant dips his finger into the liquid and flecks it into the air as an offering to Shiva. The repository palm, brimming with the tea-colored intoxicant, is offered to the pious participants who slurp it from the outstretched hand. It is consumed in a heady ritual, a holy wine, blood of the ubiquitous gods. Repeat as desired. Chatwin was an enthusiastic cultural participant. He sought experience. I encouraged my imagination and pictured him here, in his charismatic splendor, getting high with the locals, returning to his blue room and reading Proust, head spinning. When it came round to my place in the circle, I put away my hesitation and joined in communion. It takes, I was informed, a couple months before the full benefit of the practice can be appreciated. Benefit? “Why yes. Just look at him,” Rahul, my guide said, pointing to the officiating elder. “He is 72 years old.” The man sat cross-legged in his stoned glory looking not a day over 60. “Opium keeps you young. But of course it is addictive and that is a problem.” Rahul, master of understatement.

Pascal, in a particularly gloomy mood, once said, “All of humanity’s problems stem from man’s inability to sit quietly in a room alone.” I disagree. It is (sometimes) not a problem to leave one’s room, to move. “All truly great thoughts are conceived by walking,” said Nietzsche.

I seek experiences that afford me a connection to things I deem important—connections manifesting a notion of value and worth. Sometimes those experiences are made in my room, reading—but the deeper pathways are created when I move. That is probably why I seek out the haunts of writers, not just their work, reading being so personally profound an experience. Pursuing the paths of those who have gone before affords me a degree of justification in my own pursuits. Chatwin has a line in The Songlines that captures this idea, I think: “My reason for coming to Australia was to try to learn for myself, and not from other men’s books.” It is in the world that experience thickens, making life more savory, like adding a roux to a sauce. The world can be marvelously presented in the books we read and write from our dug-in places. But moving and digging in affords one the singular opportunity to experience for one’s self in a fashion that is more visceral and physical. Indeed, I sometimes reflect that if we understood better the connectedness of existence to the world, regardless of how it is garnered, books, travel, or otherwise, we might all be gods, omniscient and mindful, mixing with the immortals. To this point, I recall reading that with a day of breathing we likely inhale a molecule that had been exhaled by Napoleon—therein lies evidence that we are indeed surrounded, that we walk and we sit, read and write, among the living and the dead.