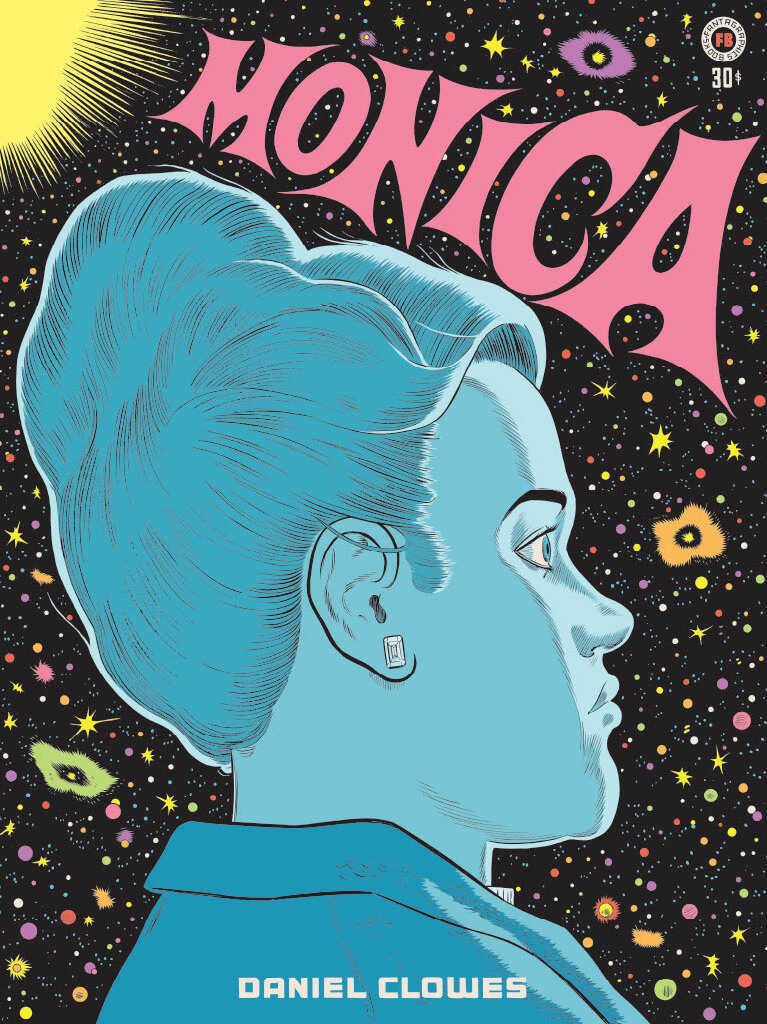

Daniel Clowes’s newest graphic novel, Monica, is a colossal achievement, a high point in a decades-long career in comics. In Monica, the titular character embarks on a turbulent journey to reconstruct a tangled family history. It’s a journey that covers a wide swath of American life—past and present—and catalogs various historical horrors and apocalyptic visions. The book is—to reference Gerard Manley Hopkins—“original, spare, strange.”

I talked with Clowes about loneliness, the mysteries of family, and The Beverly Hillbillies.

Richard Klin: There’s an element of loneliness in all of your work—from Ghost World to Mister Wonderful—that reaches fruition in Monica. It’s a big, awful lonely country.

Richard Klin: There’s an element of loneliness in all of your work—from Ghost World to Mister Wonderful—that reaches fruition in Monica. It’s a big, awful lonely country.

Daniel Clowes: I’m never thinking, “I’m going to write a book about X.” I have no information to impart. Once I got far along enough in the book that I knew what it was, it became clear to me that it was about all these different types of—I hesitate to use the word loneliness, because I’m not sure Monica’s actually lonely, but aloneness. Each story in Monica is an examination of a different type of how you can be alone. I think it’s something you can see in that first story, “Pretty Penny,” where’s she left by her mother. That was very similar to my childhood and you can see where that turns you into a perennial loner, where you’re always searching for that family that never quite emerges.

RK: Even when the family turns out to be a cult.

DC: I think we all find our way into our own little cults these days.

RK: It definitely paints a very bleak picture. Your work has always dealt with some unhappy topics, but they’ve always been leavened with an element of humor that I find less in Monica. There’s something very somber to it, as opposed to some of your other work.

DC: I find everything I do to be funny, but in a very bleak way. I can find humor in anger and uncomfortableness. My wife is always telling me that I’m the only person laughing at certain movies—I’m the one cackling like a maniac. The whole audience is, “Who’s laughing at that?” I find Monica still quite funny in many ways—on a level that I don’t expect to be transmitted to the general reader.

RK: One phrase in Monica that really stuck out to me was the “grime of madness.” I don’t know if you meant that as a societal comment, but there is something about this country that feels like it’s drenched with the grime of madness.

DC: Like a greasy coating that can’t easily be washed off. It’s not just the dust of madness. You could use all kinds of soap and disinfectant and it’s still there!

RK: Grime implies you’re trying to clean it off.

DC: It feels more permanent and more frustrating.

RK: There’s something so apropos about the endpapers—scenes of the apocalypse and The Beverly Hillbillies. I was thinking about the title of that James Ellroy book, this feeling that this country is the big nowhere. It’s a jumble of the apocalypse and The Beverly Hillbillies.

RK: There’s something so apropos about the endpapers—scenes of the apocalypse and The Beverly Hillbillies. I was thinking about the title of that James Ellroy book, this feeling that this country is the big nowhere. It’s a jumble of the apocalypse and The Beverly Hillbillies.

DC: I was thinking of that—not only the history of the world, but the history of life on earth as it turns into today. The first story in Monica begins in the early sixties. I was a small kid in 1964, 1965. What would have been the most important thing to all of us? Television. We all watched it every night. What was the most popular television show for those five years? The Beverly Hillbillies. It was something every single person would have known. Of course, there were other, similar shows, but it had the feel of the emblematic television show of that era. And it really was as important as Sputnik or anything like that in terms of the culture.

RK: There was also plenty of societal comment with The Beverly Hillbillies.

DC: [laughs] I’m a great fan. And Green Acres, I believe, is an actual surreal masterpiece.

RK: Absolutely!

DC: Absolutely hilarious. There are so many characters on that show who are the perfect emblem of a certain American archetype. Mr. Kimball, the useless government bureaucrat, who can’t remember what he’s asking… it’s just brilliant.

RK: I’ve noticed in your work and in a lot of comics, there’s more of a sense of the quotidian and the day-to-day—and I’m generalizing—than in most current literature. There’s an ear to the ground about your work. Comics are where you can read about that favorite local coffeehouse, the three bands for ten dollars. There’s an immediacy.

Clowes: The thought of writing that kind of thing in just prose seems daunting to make it interesting. Somehow bringing it into the visual and finding the dynamic visual of the mundane—it’s a very appealing idea to me, to find the grotesque and the uncanny in the middle of something that seems so commonplace. In a comic, you can depict the world not just through the characters’ eyes, so it’s a much different experience.

RK: There’s an element of The Twilight Zone in Monica as well.

DC: I saw those Twilight Zone episodes when they first aired. I was a little kid, three or four years old. My brother was a sci-fi obsessive and it was his favorite show. To this day, they feel unlike anything else. The best episodes feel like dreams that we all shared.

RK: Monica walks the fine line where it’s uncertain if some of the events are imaginary or real.

DC: To me, the interest in comics lies in that idea: Is the image reality and the words are filtered through the person’s perspective, or perhaps the image is a lie and what the person is saying is the truth? I like playing with that, and sort of being on the edge of where both of those are true at the same time.

RK: Was there a guiding impetus to writing Monica?

DC: I had wanted to do something about my childhood, to try to make sense of a very complicated, chaotic childhood that no one would ever talk to me about. My mother was still alive when I was working on it. As I was doing it, I was trying to make sense of my own emotions about my childhood, but also thinking in the back of my mind that maybe this would lead to her finally explaining what happened. And she wound up dying while I was working on the book. I found myself, like Monica, with this confounding mystery of trying to figure out just the basic events of my childhood. My brother died right before my mom and so I had nobody left who even knew the facts. So it was all a mystery. But I was able, just through digging through my mom’s papers and things, to kind of piece things together a little bit. It was like a private-detective investigation. It felt very much like an episode of Mannix or something, where you’re collecting clues. I came up with sort of a semblance of the questions I had—answering those questions. Art mirrored reality very much as I was working on it.

RK: Was there ever a resolution? Monica leaves lots of loose ends.

DC: I think Monica tied up her loose ends better than I did!

RK: What’s next for you?

DC: I have some ideas. I don’t know if I’m going to do another book that takes seven years. My goal is always to have something in the next two or three years. I have a bunch of ideas, but right now, doing the promotion for this book, I find I’m still drawn back into this book, still thinking and living in that world. And I really have to put that all away after this is over and move to the new place before I can really do anything useful.