I was on the roof of my Brooklyn apartment building, in the dark, beating boiled daffodils with a rolling pin, when I had to admit that my path might be a creative, not an academic, one.

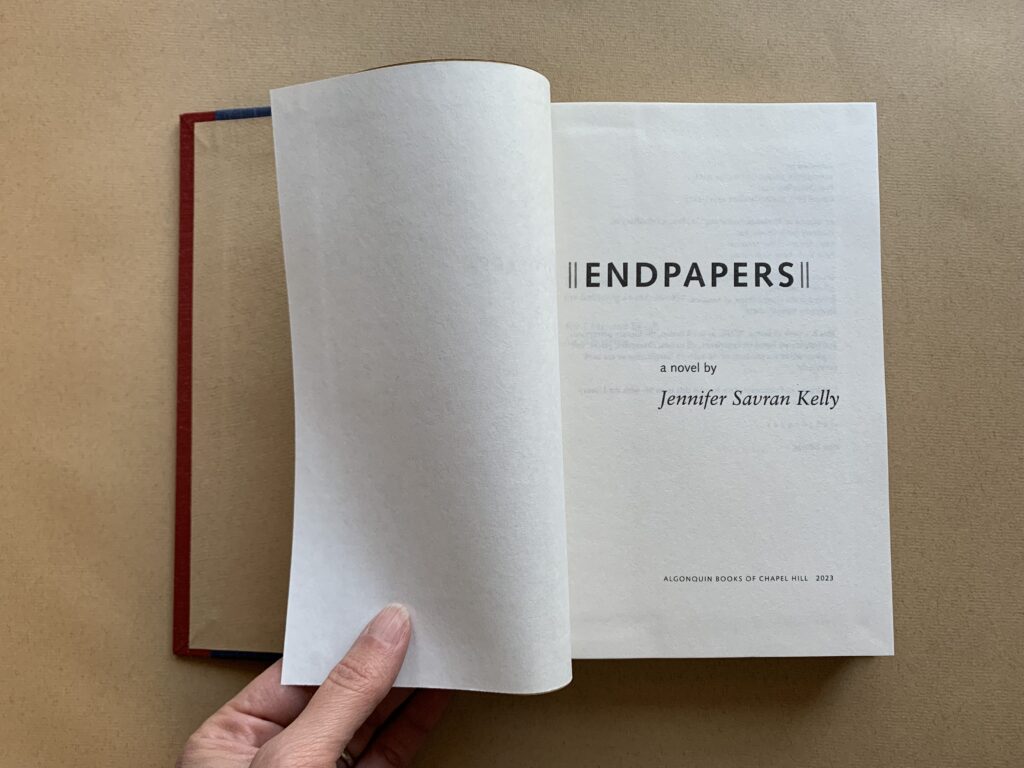

I’d been applying to doctoral programs in English lit so I could spend my life reading and writing about great novels. The truth was, I longed to write one of my own, but the idea seemed out of reach. I’d written many things in my life—countless journal entries, long letters to friends, even a short story or two that I stuffed away in a drawer—but I never saw myself as a writer. I was a book lover. A reader, to be sure, but also a true lover of the book as a physical object.

When I first lived on my own, I got hold of a papermaking kit and turned my small kitchen into a studio for boiling and blending flowers and soaking old paper to make new, richly textured sheets. It was exhilarating, but how could I forge a creative path out of crude handmade paper, not to mention a lack of belief in my own writing? A PhD in English looked like the best direction. Fortunately, most of the admissions committees and I arrived at the same conclusion: It was a poor fit.

Some of my earliest memories come from elementary school, listening to my fourth-grade teacher, Mrs. Abresch, read aloud to the class. As I’d lose myself in the story of the day, I’d also be transported by the sounds of the book itself—the crinkling of the library cover, the whisper of pages turning. It intensified the magic, filling my small self with awe about the mysterious mechanics that held the leaves together. Which seemed somehow bound up with the magic of how the words had come to the writer.

The first time that Jorge Luis Borges heard Keats read aloud by his father, he was similarly entranced. “[W]hen the fact that poetry, language, was not only a medium for communication but could also be a passion and a joy—when this was revealed to me, […] I felt that something was happening to me,” he said in a 1967 lecture. “It was happening not to my mere intelligence but to my whole being, to my flesh and blood.”

A few years later, when I received a Crayola calligraphy set for Hanukkah, I spent endless hours learning how to form each letter. On day trips to New York City, I began to admire the graffiti with new attention. When I got to college, I became obsessed with William Blake and Jenny Holzer, whose words were never just words. In a 1997 interview with Diane Waldman, Holzer said that even her street posters had to be designed thoughtfully: “I wanted the typeface for the [Inflammatory] Essays to be italic and bold and just so. The posters had to be brightly colored and to be pure squares so that people would want to come up to them. It’s just taking care.”

DW: And it’s seduction.

JH: And seduction. Careful seduction.

When I graduated and set up my little papermaking studio, I was seduced by Kate’s Paperie, New York’s epic stationery store full of decorative papers. One day a cashier asked if I knew about the Center for Book Arts.

Reader: If this were a movie, here would be the moment when time stands still.

Immediately, I signed up for a workshop at the Center. Soon after, I found a bindery near my apartment and cold-called the owner to ask to intern. Within months, she led me to the Thomas J. Watson Library at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, where they were looking for a volunteer, and within a year, I was hired there as a conservation associate.

Over the course of those whirlwind few years, I studied every aspect of bookmaking, from letterpress printing to professional handmade papermaking to conservation. What I hungered to do, however, was make artist’s books, works of art in book form full of images and words. Yet I held myself back because I wasn’t a writer. Happily, the allure of the artist’s book was strong. A promise that a book could be anything—a sculpture, a mobile, even a meal. It was new terrain to me, with no rules, no preconceptions about what kinds of words belonged on its pages.

Finally, I took the leap, searching for words wherever I could find them—eavesdropping on conversations, combing subway ads, fishing for marginal notes in used books. Unburdened by ideas of traditional narrative or knowledge of poetry, I let the shapes and sounds of words guide me as much as their meaning. How did they look on the page, play with my drawings, interact with the paper’s texture and the style of binding?

When the graffiti artist Geser was asked how he felt the first time he wrote, he said: “I remember […] not knowing how it was ‘supposed’ to look like, just having fun watching the paint come out of the can like a magic wand.” The artist’s book was my magic wand.

It still wasn’t until years later that I found the courage to write fiction. I’d recently had a baby, which meant no time for my bindery, and I needed to hold on to a creative practice. At first, I tried to emulate my favorite literary writers, like James Baldwin and Marilynne Robinson. This was literature; it required a certain seriousness. In order to hone my literary voice, I sought out a creative writing class—only to find that my adherence to “good writing” seemed to be stunting my work.

One day while I was taking a walk, the wind blew, sending a leaf scurrying across the street, and I thought, Wind pushes. I didn’t know why, but those words kept repeating in my mind. Later I drafted a story using them as the first sentence, and the result read nothing like what I thought a short story was supposed to be. When I nervously workshopped it in class, however, my teacher said it was the best thing I’d written. Later it became the first story I got published in a national literary journal.

You could say I’d found my voice. But really I began to understand that my joy as an artist had come not from following rules that govern good art-making but from giving into seduction. When I gave into the magnetism of that image and the sound of those words—wind pushes—I approached writing the way I’d approached artist’s books. And something special happened.

Most of my writing wouldn’t be considered experimental, but to disregard rules doesn’t always mean abandoning the more traditional writers who’ve come before. I will always devour the great literary talents. But as a book artist I’ve learned to follow inspiration wherever it comes from, to be guided by a sense of awe for words as art, and to view writing as less of a conversation than a palimpsest, in which we’re all layering words over the ghosts of other words, making them dance together in ways we can’t necessarily see—working not merely on our intelligence but on our whole being.