What is the point of communicating if no one is willing to hear you—if people talk over you, negate you, subtract you from whichever room you’re in? Lucy Ives’s latest novel, Life Is Everywhere introduces us to the protagonist, Erin Adamo, on page 40, lets us spend some time with her, then directs our attention to the contents of her bag for 250 pages before returning us to her life. By the time Erin enters the story, we have already read a 14-page history of botulinum toxin and spent a while in the perspectives of substitute professor Faith Ewer and Faith’s nemesis and co-teacher, Isobel Childe. So when Erin first appears, we expect her to recede again, which is what everyone else expects of her.

But Erin lingers, irritating several characters throughout the book. No one seems to enjoy contending with her presence. They want her gone as quickly as possible, or to be someone else, or a blank slate to reflect the self-affirming story of their own superior intelligence, worldliness, style, etc. When Erin visits her parents, they’re furious that their guest is Erin and not Erin’s husband—but they’re also delighted to have an emotional punching bag. Characters are repeatedly enraged by Erin’s lack of presence, which just makes them want to squash her flatter, into nothing. How can Erin possibly communicate if she is negated every time she tries? How could anyone?

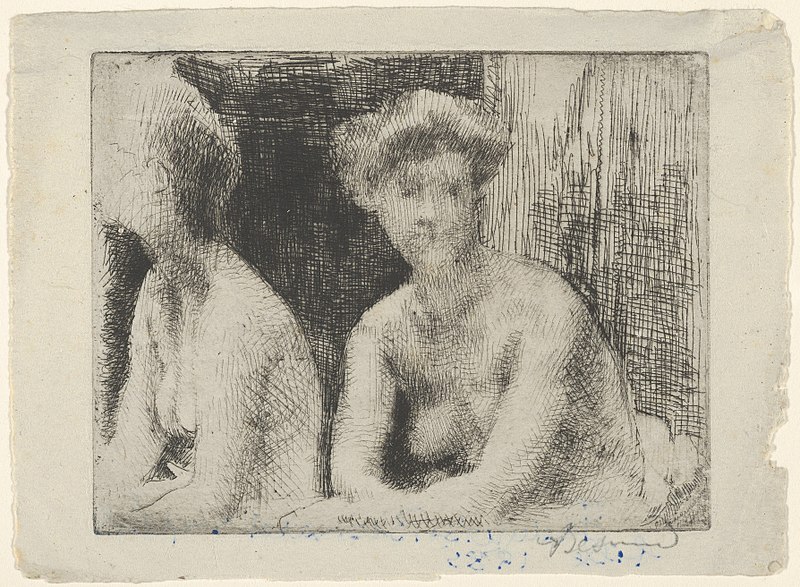

French actress Sarah Bernhardt, who is cited briefly in the novel, offers one option for being heard: cultivate an air of defiance, becoming larger than life, undeniable. Born to a Dutch Jewish courtesan and an absent father, she did not come from institutional power but became an institution herself. She had—or sculpted—the kind of outsized personality that made this possible: sleeping in coffins, pressuring her paramour to rewrite Shakespeare for her starring role in Hamlet, feeding her pet alligator “too much” champagne. But such excess isn’t always a viable option: Erin expects to be ridiculed for drawing any attention to herself—and her expectation is correct.

French actress Sarah Bernhardt, who is cited briefly in the novel, offers one option for being heard: cultivate an air of defiance, becoming larger than life, undeniable. Born to a Dutch Jewish courtesan and an absent father, she did not come from institutional power but became an institution herself. She had—or sculpted—the kind of outsized personality that made this possible: sleeping in coffins, pressuring her paramour to rewrite Shakespeare for her starring role in Hamlet, feeding her pet alligator “too much” champagne. But such excess isn’t always a viable option: Erin expects to be ridiculed for drawing any attention to herself—and her expectation is correct.

Another way to be heard is through disguise, a double life. Shed the you-ness that everyone’s familiar with, so that your words can flow unimpeded by other people’s preconceptions of the person uttering them. Perhaps the most famous example of this is the play Cyrano de Bergerac, written by Sarah Bernhardt’s lover, Edmond Rostand. (Ives herself is a fan; the play features heavily in the afterword to her 2019 novel Loudermilk: or, The Real Poet; Or, The Origin of the World). Cyrano is set in seventeenth-century France and follows two men who fall in love with the same woman, Roxane, and join forces in their efforts to win her love. Christian is handsome, but dull; Cyrano is a swashbuckler and a devastating wit who knows how to speak romance—but he has a big nose, so obviously nothing is going to work out for him. Christian is the face of the operation; Cyrano feeds him his lines and writes romantic letters on Christian’s behalf. Like two kids stacked in one giant trench coat, the pair becomes, briefly, a mecha-wooer.

Another way to be heard is through disguise, a double life. Shed the you-ness that everyone’s familiar with, so that your words can flow unimpeded by other people’s preconceptions of the person uttering them. Perhaps the most famous example of this is the play Cyrano de Bergerac, written by Sarah Bernhardt’s lover, Edmond Rostand. (Ives herself is a fan; the play features heavily in the afterword to her 2019 novel Loudermilk: or, The Real Poet; Or, The Origin of the World). Cyrano is set in seventeenth-century France and follows two men who fall in love with the same woman, Roxane, and join forces in their efforts to win her love. Christian is handsome, but dull; Cyrano is a swashbuckler and a devastating wit who knows how to speak romance—but he has a big nose, so obviously nothing is going to work out for him. Christian is the face of the operation; Cyrano feeds him his lines and writes romantic letters on Christian’s behalf. Like two kids stacked in one giant trench coat, the pair becomes, briefly, a mecha-wooer.

Cyrano is fiction, but there are plenty of real-life people, often artists, who speak through other identities, usually invented ones, to be heard. Men notably use pseudonyms for pranks, experiments, or to cultivate intrigue (Marcel Duchamp, under the name “R. Mutt,” submitting a urinal to an art show; Fernando Pessoa and his heteronyms; who the fuck is Banksy really; etc.). Women use pseudonyms to gain entry to a platform, to be taken seriously, or to protect their dignity. (The Brontë sisters published under male—or ambiguous—noms de plume; abstract expressionist painter Grace Hartigan signed her early works “George Hartigan” to increase their odds of inclusion in exhibitions; see also: H.D., George Sand, George Eliot).

Events, people, and objects discovered to be stand-ins are constant in Life Is Everywhere. This novel runs on splits, doubles, masks, and decoys. There are twins who are not twins, historical figures who might be framed as the wrong gender and who may not have existed, Botoxed faces that conceal true emotions below mask-like serenity. Things stand in for other things: two substitute teachers taking over a class, a broken statue’s hand comprising an entire liberated being, autofiction in place of personal history, romantic love in lieu of fulfillment. With so many substitutions, there is an ongoing game about what is real vs. what is really real, which is funny because in a novel, nothing is really real.

With its protagonist who shrinks to accommodate the world around her, the novel explores the mutability of selfhood. For Erin, who battles internal as well as external obstacles, her choices are not as simple as “Pretend to be confident” or “Decide to be assertive.” She compartmentalizes, another form of masking or splitting. Beyond not being able to exist on her own terms around other people, Erin is something of a stranger to herself. Based on what we are shown, this is partly due to a constant barrage of domineering personalities (her parents, her husband, her teachers) rendering any individuality on her part moot. (How could she have preferences or habits when there is no room for them? And then why does their absence make everyone so angry?) The only descriptor Erin has for herself—which other people agree with—is “insane.” Erin can know and simultaneously not-know things; she’s had traumatic experiences she only sometimes remembers. One senses there is more that she’s not able to confront.

This character and this novel are fascinating for the way they show these tangled and intersecting struggles: that of the creative impulse (“What do I mean to say and how can I get anyone to hear me?”) and that of a traumatized psyche (“Who am I really and how could I begin to know what I mean to say?”). This conflict must be reconciled to some degree by all artists, anyone who makes anything. But making things also enables artists (perhaps even more than non-artists) to cultivate an intimacy with the psyche that even the domineering personalities around us cannot overpower.

Erin is a writer, but she compartmentalizes so much that she writes her poetry and fiction in a kind of trance state; when she comes to, she discovers having written—as though the words travel through her but are not hers. (Something similar happens in Ives’s Loudermilk: A student, Clare Elwill, cures her writer’s block by subtracting herself from the process, willing a delusion that she’s not the author of her own work—“She might be anyone; who cares who is doing the writing.”) Erin’s novel, which features a protagonist grappling with her husband’s infidelity and the dissolution of a marriage, was written before Erin became consciously aware of her own husband’s affair, and before their resulting decision to separate. In hindsight, Erin believes her fiction “predicted” these events. Ives produces Erin’s entire novel within the pages of Life Is Everywhere, so we can see what her novel “knew.” But both of Erin’s creative works—this novel, and a novella written from a child’s perspective—feature enough allusions to abuse and pervy dads to raise an eyebrow. There may be more that Erin’s writing knows, that she is not ready to know.

Ives has written that she’s fascinated by the various interpretations of Life Is Everywhere, making the book seem like a Rorschach test. There is so much information in its 500 pages, allowing different people to see different pieces glittering, different threads we believe are The Real Story. Explored here are the parts that connect with something in me, that glint under my own gaze, that I can digest and make meaning from.

The format of Life Is Everywhere reproduces the difficult act of remembering. Given the various texts within the text, and the fact that none of the events are really real, readers may conflate fictional “facts” with fictional fictions. Ives relays Erin’s life through close third-person narration as well as Erin’s own first-person fiction manuscripts. Sections-related-to-Erin exist in these two modes (third-person “reality” and first-person fiction) and are interrupted by other texts—academic papers, a utility bill—replicating the protagonist’s own patchy understanding of herself and her own story, and replicating how traumatic memory is stored and retrieved. There are things I think I know about Erin that I cannot separate from what the characters in her stories have said or done. It’s an incredibly smart craft choice, leading to a feeling of empathy for Erin’s struggle with memory and identity.

What is the point of communicating if no one is willing to hear you? Near the end of Life Is Everywhere, a literary agent tells Erin that her work is unsuccessful “in part because the protagonists’ troubling lack of agency is never fully explained,” as though a fish might have a name for water. The agent has deemed the work unsellable in its current state. But it is not valueless; it is the only thing that has been Erin’s alone, kept private and protected from her parents, from her philandering husband. Sure, it has been rejected (by one person!) for an audience, with a request to contort it into a more recognizable shape, to make it scrutable to strangers. But what if the only audience that matters is Erin? What if the person she most needs to communicate with—and to hear—is herself, before she can get to a place of engaging with other people—in art, and in life—on her own terms?

After receiving this rejection from the agent, Erin feels compelled to translate an enigmatic story from French—a story she believes was meant for her. In it, an enchanted object instructs a young girl: “Go into the world and look like what they call you but be something else and never return.” Look like what they call you but be something else. What if whatever splitting, masking, or doubling Erin does is how she buys time and seclusion for a private ongoing dialogue with herself, the work of becoming a whole person?

Unlike Erin Adamo, Cyrano de Bergerac is depicted as a self-possessed, whole person—with one arguable defect he believes he must contort around to avoid a rejection he’s not even certain of. Erin meets rejection after rejection, even as she bends to everyone else’s will. But her writing doesn’t bend. Erin’s situation is of course different from Cyrano’s, but authoring fiction offers them both a way through. For Cyrano, pretending to speak for someone else allows him to be honest about his tender feelings; pretending to lie is his only avenue for telling the truth of his love (and only he knows this is his truth). Similarly, writing fiction is Erin’s outlet for telling herself the truth of her life. Compartmentalization can save us from ourselves and our memories, at least for a while. But art can show them to us when we’re able to receive them.