Prince Harry’s ghostwriter is making my job harder.

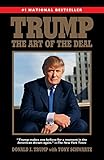

I’ve ghostwritten more than 80 books since 2011, and as of late many potential clients have expressed to me that they are nervous and unsure about moving forward with their project. Their biggest concern? That I might spill the beans on them, just as ghostwriter J.R. Moehringer, hired by Prince Harry to pen his bestselling memoir, Spare, has done, and as the ghostwriter behind Donald Trump’s Art of the Deal, Tony Schwartz, did before him.

I’ve ghostwritten more than 80 books since 2011, and as of late many potential clients have expressed to me that they are nervous and unsure about moving forward with their project. Their biggest concern? That I might spill the beans on them, just as ghostwriter J.R. Moehringer, hired by Prince Harry to pen his bestselling memoir, Spare, has done, and as the ghostwriter behind Donald Trump’s Art of the Deal, Tony Schwartz, did before him.

“You’re not going to do that to me, are you?” they ask.

To be a ghostwriter is to enter into a particularly intimate relationship, akin to being someone’s criminal defense attorney, their tax accountant, or their therapist. You get to know them, warts and all, as you help them craft a book that tries to present their best selves to the world. You even learn to write in their voice. So the cardinal rule of ghostwriting is simple: Never make the client look bad.

Moehringer has broken this rule in spades lately, starting with cryptic tweets about errors that appear in Spare and, more recently, a lengthy airing of grievances in The New Yorker. The piece troubled me from the very first paragraph, which describes a moment in which he was arguing with Prince Harry while working on the book, who then jokes mischievously that he likes to get Moehringer worked up—a scene that, it seems to me, he did not have Harry’s permission to describe. This, to me, would be like opening a magazine to read your doctor describing an argument with you during a checkup, including your name and personal details about your medical history. (Imagining, of course, that you and your doctor’s relationship is bound by good faith rather than HIPAA.) How could you trust any doctor again?

To be fair to Moehringer, a Pulitzer Prize-winning writer, the temptation must be great. Everything to do with the royal family is picked apart in the British tabloids, and ghostwriting a juicy tell-all from one of its most obsessed-about members is an especially ripe topic. But within the industry, the informal code that ghostwriters follow (in theory) demands that we let the book speak for itself and stay out of the limelight. Our role is more or less invisible—we’re called ghostwriters, after all.

Moehringer knows this. “For the thousandth time in my ghostwriting career,” he writes in the piece, “I reminded myself: It’s not your effing book.” But he clearly struggles with this very simple commandment, recalling that he once yelled at a TV for tennis champion Andre Agassi, for whom Moehringer ghostwrote the autobiography Open, to mention his name during an interview.

Moehringer knows this. “For the thousandth time in my ghostwriting career,” he writes in the piece, “I reminded myself: It’s not your effing book.” But he clearly struggles with this very simple commandment, recalling that he once yelled at a TV for tennis champion Andre Agassi, for whom Moehringer ghostwrote the autobiography Open, to mention his name during an interview.

Ghostwriters aren’t supposed to take credit. In the best-case scenario, our job is to help someone with a lot of knowledge and ideas put them down on the page in a structure and style helps the reader. And there are times where the client also wants to pass the book off as entirely their own work—there’s nothing wrong with that. The truth is that the ghostwriter isn’t writing the book for you but with you.

When I tell people what I do at a party, they assume my job is a secret. That can be the case when a ghostwriter is just starting out, or perhaps has earned a bad reputation, but I’ve found that the more successful I get, the more my clients want readers to know they work with me. Some clients think it may even help sell more copies.

There’s also in recent years been a bit of a sea change in the industry, with clients just generally being more open about their use of a ghostwriter. I first noticed the shift about five years ago, when clients began inviting me to go on YouTube and talk about how we put together the book, or name-checking me on social media and in interviews. One client recently suggested that my name appear on the cover as well. In other cases, clients will single out the ghostwriter in the acknowledgements, which is much more subtle. To those of us in the industry, this very obviously signals that they used a ghostwriter, though the average reader won’t catch the reference. Personally, I appreciate whatever acknowledgement a client wants to give me, but I’m also fine if they want to avoid the topic. That’s why they pay me. I have never, in my career, yelled at a TV for a client to say my name.

Even without the issue of acknowledgement, it’s still important for ghostwriters to avoid criticizing their clients. My own clients tell me about their lives in extensive detail. I sometimes have to convince them to open up about some of the most difficult situations they’ve faced and the lowest points in their lives. Many times, a client will hesitate, take a breath, and say to me, “I’ve never told a single soul this, not even my priest.” What follows is often an incredible story that can make the book.

My job in that case is to take care to tell that story in a way that’s good for the book and good for the client, to share their experience in a way that’s empowering and enlightening. And at times, I’ve even found that, while it’s a great story, it simply doesn’t belong in the book. Those stories I keep with me, locked away. Maybe they’ll end up in the client’s next book, or maybe they won’t, but they’re not mine to share, and certainly not in a public forum.

Of course Moehringer is not alone in breaking our profession’s cardinal rule. Trump’s ghostwriter on his 1987 memoir The Art of the Deal famously came forward to give a lengthy interview criticizing him just ahead of the Republican National Convention, saying he “put lipstick on a pig” and expressing his “deep remorse” for his work on the book. And more recently, Gwyneth Paltrow publicly denied using a ghostwriter after the New York Times interviewed a collaborator on her cookbook, My Father’s Daughter (though the article itself was fairly tame).

Of course Moehringer is not alone in breaking our profession’s cardinal rule. Trump’s ghostwriter on his 1987 memoir The Art of the Deal famously came forward to give a lengthy interview criticizing him just ahead of the Republican National Convention, saying he “put lipstick on a pig” and expressing his “deep remorse” for his work on the book. And more recently, Gwyneth Paltrow publicly denied using a ghostwriter after the New York Times interviewed a collaborator on her cookbook, My Father’s Daughter (though the article itself was fairly tame).

It can be hard to stay offsides. Every ghostwriter has a story to tell about a particularly difficult client or the peccadilloes of a famous person they observed up close. But while our job may be to tell stories, there are some we should keep to ourselves.