July

So to Speak by Terrance Hayes

So to Speak by Terrance Hayes

Whether in free verse or in sonnets, Hayes builds energy in his poems through recursive language and inversion of phrases. This method is quite successful, imbuing a dually playful and disarming sense to his work. “Ladies & Gentleman put your hands together / for Kareem Abdul-Jabbar’s beautifully iambic name,” he begins a poem early in the collection. “Do not think of all the tall in him / squeezing into a stall at the mall as strange. // Some days his father whispered to himself / Someday that boy’s going to change his name.” His tonal shifts pierce the page; whimsy is appended with sentiment, as in “American Sonnet for My Grandfather’s Love Child”: “My mother changed her name / To daughter, then to sister, then back to mother again.” The same gentleness arises in “Blood Pressure Medicine”: “that terminal quiet / between hearing her // close the door of the bathroom / and open the bathroom mirror.” Admirers of Hayes can spend their summer shifting between So to Speak and his simultaneously released book of prose, Watch Your Language: Visual and Literary Reflections on a Century of American Poetry. There Hayes examines his poetic lineage through divergent prose forms (lists, short profiles, questionnaires, journal entries, imagined blog posts). This is a wildly entertaining and honest view into a poet and artist’s rangy mind.

August

I Done Clicked My Heels Three Times by Taylor Byas

I Done Clicked My Heels Three Times by Taylor Byas

Early in her full-length debut collection, Byas follows Sylvia Plath’s “Blackberrying” (one of her best poems) with her own interpretation. “Children in the yard, and nothing, nothing but blackberries,” she begins, the first line springing the poem forward, as “blackberries culled from the waist-high bushes, the blister-bumps / smashed down to seed and muck, then handprints on white / button-downs and knee-highs.” Byas’s word choices ripple and rise, the juicy hunt for berries turning into a meditation on body: “Blackberries slit then quickly squished, berrying / down the sides of my fingers, wet splints for the joints. / I could not tell if my mother’s sighed requiem was for the fruit / or my ruined clothes. Perhaps she lamented the deep red stain // on my hands, mistaken for the first sample of womanhood.” She continues these richly described moments in poems like “When the Air-Conditioning Breaks”: “We discover home-grown auto-tune and yawp / our Vaselined lips mere inches from the box fan’s lettuce—the flowered blades compute and swap / our breaths for robot, monotone.” Byas’s details both direct us toward sounds and are acoustically robust, a poem in a poem. In “Sunday Service,” after the organ player launches into song, “the spirit hits the pews in waves.” Congregants speak in tongues. Necks loosen. the narrator’s “grandma starts to convulse.” Around her, congregants “flitter fans / like mosquito wings.” The narrator, because she can do nothing else, clasps her hands in prayer. “I repent for things / I’ve yet to do. They jerk to tambourines.”

The Kingdom of Surfaces by Sally Wen Mao

The Kingdom of Surfaces by Sally Wen Mao

Mao’s collection ends with “On Garbage,” one of my favorite poems of the book—one of those book-anchoring pieces that sends you back through a volume. “Every day on the back of our ‘89 Mitsubishi Galant, / I searched the curbs for previous garbage.” The narrator notices what her parents, “scraping by,” had tossed: old televisions, couches, and coffee tables. She “learned to love garbage // because it gave me hope / to rescue what was abandoned, / what was beyond repair.” What care she takes with the details: “I prized even the broken things: the TV sets // with bent antennas, the moth-eaten lace, the paperbacks // dropped in bathwater.” Lineage is a mainstay of The Kingdom of Surfaces, as when Mao writes elsewhere of how a narrator, perpetually coughing as a child, was given yellow loquats as a child to calm the sickness. Now, she describes, “my cough // grows and grows. There is a tree or a fungus / in my chest. I once kissed a man in the hollow, // a tattoo of a tree stump on his chest.” Mao’s narrator’s are haunted (sometimes pleasantly so) by their past, as in “Wet Market”: “From youth I was taught that fresh meant alive / until the moment you buy it.” So many gorgeous, sharp lines in this book that often reveal the pain beneath. A stirring collection.

I Love Information by Courtney Bush

In “Jubilate Agno,” a poem that follows Christopher Smart’s bizarre 18th century verse, Bush’s single line stanzas create a drifting, nearly hypnotic feel to her lines, an acutely cinematic touch: “A music teacher shops late at Walmart // In a sweatshirt covered in little fish // In the middle of an incurable nervous breakdown.” The narrator “found mysticism in a ranch-style house,” and whose lover “impaled his hands on a barbed-wire fence // Ending up with stigmata at Kelli’s farm // He’s waving white arms on the esplanade.” In Bush’s comfortably disjointed poems, surprise and pleasure are nearly constant, each line its own song. She saves profluence for clever pairings, as with: “What’s the youngest you’ve ever been / And the youngest you could ever bear being again” and “If you want to be hysterically funny / Write out the logic of anything.” Bush writes at the convergence of modernity and mysticism, turning her poems inside out (“Sonnet,” she writes in one piece, “it’s time for you to do what you said you would / I’m talking to you now / You will do this for me / You will think.”). She can also be revelatory in her whimsy: “I don’t think language can fail / Fail to do what / You wouldn’t ask experience to be language / You wouldn’t mop with a tennis ball.”

In “Jubilate Agno,” a poem that follows Christopher Smart’s bizarre 18th century verse, Bush’s single line stanzas create a drifting, nearly hypnotic feel to her lines, an acutely cinematic touch: “A music teacher shops late at Walmart // In a sweatshirt covered in little fish // In the middle of an incurable nervous breakdown.” The narrator “found mysticism in a ranch-style house,” and whose lover “impaled his hands on a barbed-wire fence // Ending up with stigmata at Kelli’s farm // He’s waving white arms on the esplanade.” In Bush’s comfortably disjointed poems, surprise and pleasure are nearly constant, each line its own song. She saves profluence for clever pairings, as with: “What’s the youngest you’ve ever been / And the youngest you could ever bear being again” and “If you want to be hysterically funny / Write out the logic of anything.” Bush writes at the convergence of modernity and mysticism, turning her poems inside out (“Sonnet,” she writes in one piece, “it’s time for you to do what you said you would / I’m talking to you now / You will do this for me / You will think.”). She can also be revelatory in her whimsy: “I don’t think language can fail / Fail to do what / You wouldn’t ask experience to be language / You wouldn’t mop with a tennis ball.”

September

Have You Been Long Enough at Table by Leslie Sainz

Have You Been Long Enough at Table by Leslie Sainz

Sainz confronts tension through each poem in this collection, her work often set in a world where mysterious forces abound. In “Mal de Ojo,” the narrator “made another woman my enemy / I followed her for three blocks before I tripped over my envy.” In “ Sunday, Wounded,” after Mass, “The women feed their missing / to the church walls, // the women derange the street with their dead.” Her speakers tempt fate, as in “Sonnet with Ogun:” “Later, when I clean the kitchen, I drop a knife on the floor / / again and again just as an excuse to touch it.” Sainz’s narrators court love and loathing. “Gladiolus, ginger, lilies” she writes in “A Story of Love and Faith / La Milagrosa,” “Young / women are a series of images. We are regimes.” So many of Sainz’s lines carry the weight of a culture—poet as medium: “Eventually, we cried so often we were forced / to invent salvation.” In “Ars Poetica,” she captures the center of her ambitious project: Cuba/America, Spanish/English, tradition/self: “You skewer / all the present moments // with a fork. They squirm / spectacularly, like second languages.” A promising debut.

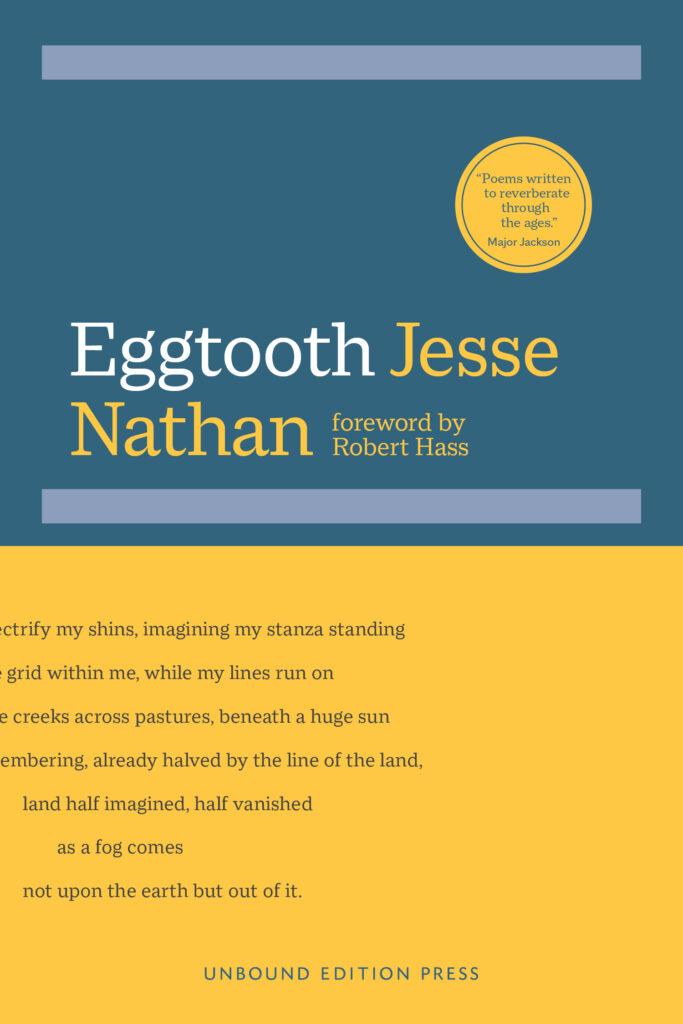

Eggtooth by Jesse Nathan

In the introduction to this collection—written by no less than Robert Hass, former U.S. Poet Laureate—we learn that Nathan is both Jewish and Mennonite, the latter reflected in a scene from “Footwashers,” an evocative piece. Nathan begins the poem with a description of the building, “stout as a dancehall, white clapboard and square.” His mother “in her special vamps” and his father “in his monkstraps” moved among the pews toward basins full of “warmish water lapping.” Here the congregants would “cradle, douse, and bathe” the feet of their neighbors—hands rubbing heels and insteps. Surrounded by “faint funk or toenail paint,” tens of hands working over feet, the narrator sees relatives, the sheriff, and others from the town. The poem ends “as I towel off a sprouting / cousin’s fallen arches, anklebone, / all thirty three joints known and unknown / that carry me away from home.” The poem is representative of Nathan’s ultimate poetic skills: he’s attentive and observant, and although his past has definitely passed from his life, he resists the flattening nature of caricature. Eggtooth is a work of nostalgic wonder: “Trust I was—am—that boy who’d lope and stalk / across the frosty fields with the dog, play at random / turning into circles, running wider / and wilder.” It is also a work of mystical observations. In “Shock” “As the storm moved in, I watched the night / before I slept. A biblical clap woke the house / to sprays of sheetrock, a powdered sprite / springing from the nailheads.” Nathan’s close manner of attention renders the prosaic powerful.

Pig by Sam Sax

Pig by Sam Sax

The latest collection from the inventive and original Sax opens with a diagram of cuts, segmenting the animal from head to jowl to bacon to hind feet. A gesture of parts-as-a-whole, a fitting framing for the book: pig is metaphor and matter, source of subversion and metaphorical permanence (“pig existed before we had tongues / to name it”). In “Sic Transit Gloria Mundi,” the narrator shares: “my grandfather castrated pigs as a child / he tells me this casual as bread / when I bring up the book I’m writing.” Sax’s poems often operate as catalogs of conversations, alit by the poem and book itself (so that Sax’s writing and work and life intertwine; he playfully wonders at the end of one poem, “what would i learn if i were to write / this book on an entirely different subject: / antique clock repair / the sex lives / of astronomers, joy.”). As the poem continues, the narrator imagines his grandfather at work, “hands the size of pastures / filled with castrato pigs singing opera oddly / wagner probably.” No one is more surprised than him: “one moment you’re drinking a cheap beer / in a velour jumpsuit and the next / you’re descendent of jewish pig farmers.” Elsewhere, Pig is a litany of names and things unsaid: “i who have been // addressed & became, have lain // with men who never bothered // with names & still, when it comes // time for it they always find // something to say.”