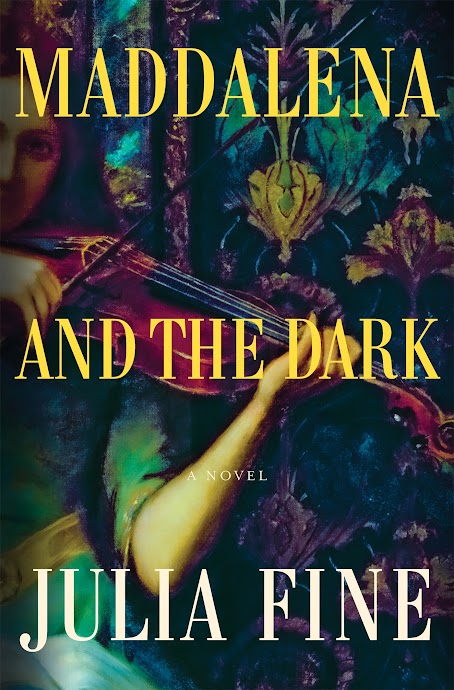

In Maddalena and the Dark, Julia Fine invites reader to enter the cloistered halls of the Ospedale della Pietà—part-convent, part-orphanage, part music school—where young orphaned girls in 18th-century Venice were trained to become members of elite all-female orchestras. Banished to the Ospedale by her noble but scandal-prone family in 1717, the titular Maddalena finds an intense friendship in Luisa, an orphan who desires nothing more than to prove herself worthy of Vivaldi’s violin solos. By making a bargain with a mysterious denizen of the Venice lagoon, Maddalena thinks she can restore her family’s fortunes and secure Luisa’s musical future. But while the girls are inseparable inside the Pietà, they soon find themselves competing for power and security outside its walls.

I spoke with Fine about writing routines, violin technology, and researching Venice from afar.

Irene Katz Connelly: Tell me what drew you to Venice as a setting.

Julia Fine: I had been working on a different project that didn’t have a spark, and I was thinking about what I could do instead. And I remembered that as a child, I had these audio cassette tapes called Classical Kids, where they wrote stories about the lives of different composers and excerpted little pieces of music. One of my favorites was called “Vivaldi’s Ring of Mystery,” and it was the story of a girl who goes to an orphanage music school in Venice. I thought, “Oh my goodness, this is the setting of a novel.”

IKC: What was it like to research this book?

JF: I play piano and took voice lessons for a long time, but I do not play a string instrument. And for Vivaldi, the violin is the king of all instruments. So I read a lot about the history of the violin as an instrument and violin composition and Vivaldi himself. This was during peak pandemic; you couldn’t go anywhere, but you could go on YouTube and have access to all these really fabulous musicians teaching master classes to other fabulous musicians. I would watch these master classes to learn the language of the violin.

Then, of course, the history. I started way back at the beginning of Venice, and ended up doing a lot of reading about the city in the eighteenth century and after. The Republic of Venice ended not too long after the book, so I was interested in what signs you could see from 1717.

IKC: It seems important to Maddalena’s story that the Republic’s power is waning.

JF: Venice was in its prime during the Renaissance. By 1700, other places had the naval technology they were so proud of, and other trade routes were open. A lot of the things they had counted on to maintain their power just didn’t work anymore. It’s a very modern problem: Has your society peaked, and has satisfying all of these rich people taken precedence over preserving a culture and a way of life? The more I researched, the more I felt like this is the story of America’s class divide. There’s so many contemporary parallels, not just to the way that women artists and young girls navigate the world, but also the actual political system and what happens when an empire begins its decline.

IKC: How did the ospedale system arise? I can’t think of many other examples in European history where (some) women had this third alternative to getting married or becoming a nun.

JF: By 1717, things were falling apart, but Venice’s republic did work really well for a really long time, and Venice did a good job of taking care of the needs of the lower classes. The Pietà began in the 1300s as a home for the daughters of courtesans. Over time, because Venice was such a musical city, the different ospedali would compete over who had the best orchestra. So by the time you get to the early eighteenth century, these institutions are basically conservatories, and people come from all over Europe to see them.

At the same time, the engineering of the violin around this time was making a lot more possible for composers. Vivaldi was obviously brilliant, but he also lucked out in terms of having a built-in orchestra that couldn’t go anywhere and the technology to do the things he wanted to do.

IKC: For me, one of the most striking aspects of the novel is its totally unsentimental depiction of girlhood. Maddalena and Luisa know from the start that they have to take care of themselves, and they think about men, marriage, and money in pragmatic terms — no one is sitting around fretting about not getting to marry for love. Why was that important to you?

JF: Often teenage girlhood is depicted in literature in a way that doesn’t feel especially accurate to me. Particularly for the girls at the Pieta, their options are fairly limited. They’re between a rock and a hard place: In order to get married and have a life outside, they have to give up their instrument. It’s such a pragmatic decision to ask a 16-year-old girl to make. I just don’t buy that in this particular environment, anybody would be thinking, “Oh, someday my prince will come and take me away.” These girls have been through too much to think about that. I’m interested in those teenage girl relationships where you love your friend so much you’re not sure if you want to kill them or have sex with them or marry them.

IKC: Do you follow any kind of schedule when you’re working on a book?

JF: For Maddalena, my kids were one and four when I started writing. I would put them to bed at 7pm and hole up in the home office and just bring dinner with me. This was during Covid, so there weren’t exactly social obligations to turn down. But I do have a partner who bore the brunt of that in terms of not socializing or watching things. My previous book I wrote during my son’s naptime, and now I’m writing when my kids are at school.

IKC: What do you do to wind down after writing?

JF: I’m always reading something that’s totally different from what I’m working on. Exercise sometimes helps. Having a kid also helps because it puts things in perspective. There’s nothing more visceral and real than changing your kid’s diaper.