Connie Converse was one of legions of aspiring musicians in 1950s Greenwich Village. She recorded a series of hauntingly beautiful songs that featured her voice, her guitar, and her poetic, allusive lyrics. Converse had no coterie of like-minded musicians; she inhabited no scene, music or otherwise. She made exactly one television appearance. By the early 1960s, having failed in her attempts to break the shackles of obscurity, the troubled Converse relocated to Ann Arbor, Michigan, immersing herself in academic publishing and imbibing the college town’s political vitality. Then, in 1974, Converse loaded up her car, drove off, and was never heard from again. This seems utterly improbable. But these are the facts. Her ultimate fate—suicide, murder, a life lived under a new identity—remains a matter of conjecture.

Being ahead of one’s time is a cliché, but in Connie Converse’s case, it is entirely accurate. Her music stunningly anticipates the musical landscape of the 1960s. It is almost impossible to comprehend that Converse’s music was recorded in the 1950s. The idea that truth is stranger than fiction is another cliché. But this—as well—applies to Connie Converse and her strange, unknown fate.

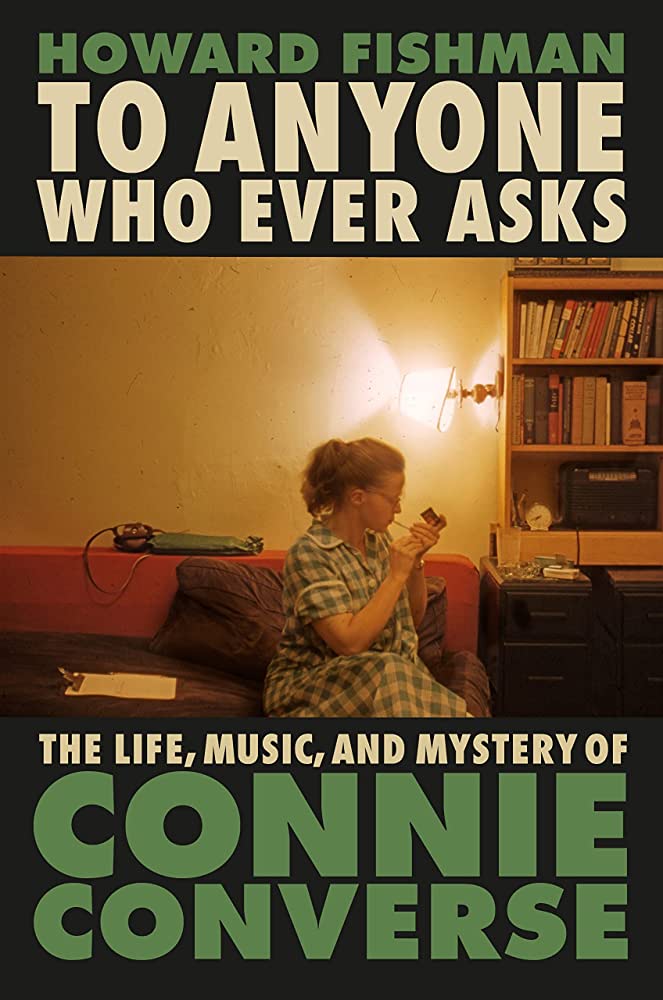

Musician and writer Howard Fishman has penned To Anyone Who Ever Asks: The Life, Music, and Mystery of Connie Converse. It is a mammoth achievement, as documentation on Converse’s life is sparse.

One huge impetus for the book was Fishman’s intense personal affinity for Converse and her music—music that exists, in his words, “out of time, out of music history altogether.”

Richard Klin: Being ahead of one’s time is a blessing and a curse. I think about that in Connie Converse’s case. She was pioneering, but it restricted her too. Her music seems to come out of the ether.

Howard Fishman: It’s just one of those unfortunate aspects of being somebody who is a pioneer that oftentimes you just don’t get appreciated in your time. It’s not like she’s the first one for that to happen to. I think it’s clear that the music she was making didn’t have a context yet. I think it’s clear that the music industry at that time didn’t know what to make of her and didn’t know how to brand her. And I think, in a way, she serves almost as the polar opposite of today’s urge to brand everything. You can’t brand Connie Converse. Even among her uniqueness, there’s uniqueness.

RK: Her music was so proto-1960s. How did she come up with that? It’s probably an unanswerable question.

HF: There’s no way to know. As I say so many times in the book, I don’t want to speculate about things that we don’t know, but my feeling is that she was really trailblazing in that the people who came after her may have picked up on some of her smoke. Maybe without even directly having heard her music, they may have somehow intuited something that had entered the zeitgeist—in a way that softened the road that would now be trod by Bob Dylan and his ilk. I do think that she preempts Dylan in terms of what she was doing—and that we need to rewrite the history books a little bit. And again, not to speculate, but I think it’s probably fair to say that along with the fact that there was not yet a context musically for what she was doing, I think the fact that she was a woman doing what she was doing made it doubly hard for her to break through. Women entertainers at that time were expected to be vixens or virgins. And she didn’t fit into those categories at all and was not interested in it.

RK: One thing that gives the book extra power is your own involvement. It’s an understatement to say you had an emotional reaction to her music. It was more than that—it was an immersion.

HF: I think that’s true. I’ve tried in different ways to explain this, as to why this happened to me. Before I started writing this book, I was a performing songwriter myself and encountering Connie Converse was sort of like encountering the best possible version of what I could ever hope to do—better than anything that I could ever hope to do. And to think, Oh my God, this was the best version of me and this is what happened to her! I felt called to do something about that—for her. To stop working on my own behalf and to start working on hers.

RK: You get the sense it was a real calling on your part.

HF: That’s what it felt like. It felt irresistible.

RK: You write, “Don’t ask how Connie Converse disappeared. Ask how she lived.” Which I think is important, but you can’t ignore the fact that she did disappear. When I first heard that she had vanished, I thought, Well, that can’t be right; I’m not hearing this correctly.Try as I might, when I was reading the book, I was attempting to basically not to think about that. But her ending is horrible and it’s bizarre. Yet it is part of her saga.

HF: I think that’s true. When I say “Don’t ask how Connie Converse disappeared. Ask how she lived,” what I mean is that the disappearance is not the most interesting thing about her. Even as interesting as a disappearance is—even that isn’t as interesting as what she actually did with her life. I feel that people who get caught up in asking, Where did she go? Are there cold cases that we can explore? Can we try to find the body? I don’t think any of that matters. Her disappearance was her way to just giving the finger to everybody and saying, You don’t want me? I don’t want you.

RK: Do we know how she viewed the crop of sixties music that followed in her wake? She’d moved to Ann Arbor and although she was still involved in music, in essence she’d said goodbye to the music world at large.

HF: Most of her music-making activities in Ann Arbor consisted of playing pop tunes of the day with her neighbors and family. As harrowing as it is for me to imagine her playing covers of the Beatles and Bob Dylan, apparently that’s what she was doing with her family. But there’s no written record of what she thought of that music. One of the most unsatisfying things about my research is not being able to answer that question. Clearly, by the time that she left for good, there was a market for what she was doing. So why didn’t she go back to it? That’s a big mystery for sure.

RK: There’s one puzzling aspect after another. And you wisely didn’t attempt to resolve them.

HF: I’m glad you didn’t find that frustrating, because that’s true. Her story is Swiss cheese. And that’s the reason that the book ended up in the form that it is, with me sort of leading the reader through it. When I initially started the book, I was writing it as a straight biography, third person. A bit more matter-of-fact, divested of any personal involvement or emotion. I realized I couldn’t tell the story that way because there’s not enough of the story to tell. I had to include my own involvement. And the questions that appeared as they came up for me are then shared with the reader.

RK: At the end of the book, you link what happened to her with the greater question of how this country ignores the artist, the nonconformist. In some ways, what happened to Connie Converse is emblematic of a very callous culture.

HF: There are great things to be said about our culture, but the way we treat creativity in our culture is not one of them. What happened to Connie Converse is sort of what happened to our culture—or what has happened to it. And that’s why I think it’s a teachable story.